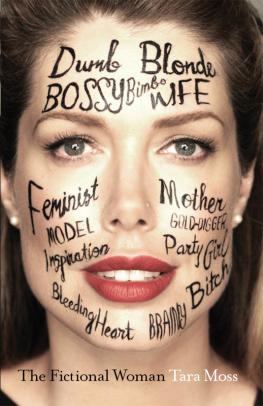

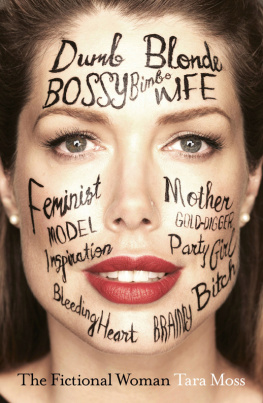

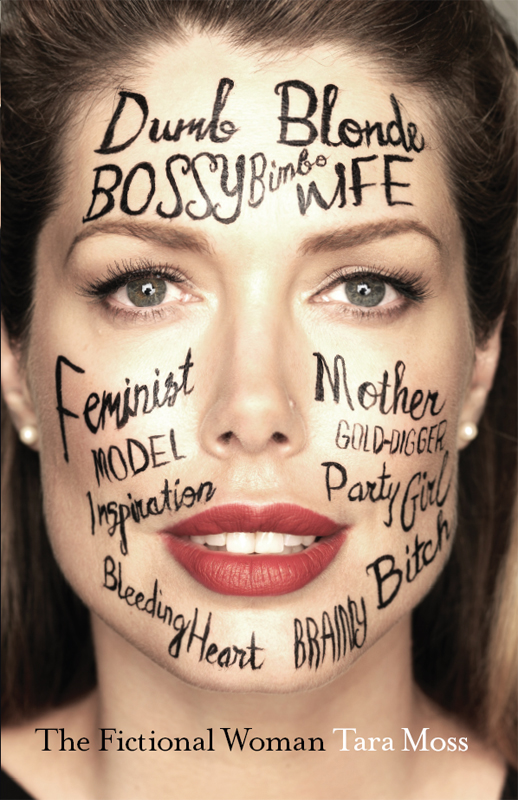

THE MODEL

How ironic this all is. Im hired for my looks, and yet it takes them three hours to make me pretty enough to photograph. Isnt that weird?

Supermodel Monika Schnarre, at age 15

I t was the first day of summer, and I was sitting in the front passenger seat of the family car sipping a Dairy Queen milkshake. The cold of the milkshake froze the metal braces on my teeth, so I had to remember not to drink it too fast. My mother, Janni, was in the drivers seat. We were parked at the scenic lookout at the top of Mount Tolmie, my hometown of Victoria, British Columbia, spread out below us.

My mother put down her own milkshake and took my hand. Tara, is this what you want? she asked, looking me in the eye. She was not referring to the milkshake, but to the sudden, rather staggering suggestion that I become an international fashion model.

In many ways, I was the most unlikely candidate for a model you could imagine. Throughout my childhood I was what many people refer to as a tomboy. I loved climbing trees and playing with toy cars. It wasnt that I hated feminine things; I just liked cars and horses and spaceships things that could go fast and take you to exciting places and planets more than I liked toys that needed to have their hair brushed. I preferred toy monsters to toy kitchen sets. My parents never emphasised that I was different or needed to change my preferences; these choices of mine were not conscious, at least not yet. And I didnt have a problem with girls clothes per se; I just hated wearing dresses because they got in the way when I was going places, like up trees.

When I was six years old, my father took me and my sister to his work picnic. Thanks in large part to my height and the long legs that came with it, I could run faster than most kids my age, and that day I won a running race. I think it was the first time I had ever won anything. One of the organisers led me to a table marked Girls Age 68 to collect my prize. The table was covered in wrapped gifts, and fearing Id be stuck with a toy I would not like, I asked if I could please take a gift from the boys table instead. The woman bent over and told me quite pointedly, No, darling, those are for boys. These are the ones for girls .

Reluctantly, I took a gift from the girls table and opened it to find my worst fears realised. It was a Barbie doll.

I held the useless doll Id won, my first prize (It doesnt do anything!) and watched through eyes swimming with tears as the winning boys collected their Hot Wheels cars and train sets and action figures. Thankfully, my mum understood. She wiped the tears from my face and explained that we could make my prize into anything I wanted it to be, anything at all. So when we got home she helped me to dye Barbies blonde hair black and add stitches to the dolls sculpted plastic cheek to transform her into a kind of Vampirella/Bride of Frankenstein monster. I loved her. (To this day I wish I knew what happened to that doll.)

In my preteen years, I became interested in makeup. I was perhaps twelve and I was experimenting with my appearance. Mostly I wanted to be David Bowie, who, truth be told, I resembled a bit at the time, physically speaking. I had grown up but not yet out. I was the Thin White Duke. In fact, I was so skinny my dad used to joke that if I turned sideways and stuck my tongue out Id look like a zipper.

By fourteen I was painfully skinny and unusually tall. Complete strangers had taken to commenting that I should be a model. Then my parents watched a TV program about an Ontario girl named Monika Schnarre. Having been discovered at age thirteen, she was now sixteen years old and six foot one, and had already launched a successful modelling career in Europe; apparently modelling agencies favoured young girls who were tall and slim. The airing of the program coincided with the semi-annual marking of our heights with pencil on the frame of the kitchen doorway. I had surpassed my older sisters impressive stature and cracked five foot eleven. I was growing fast and I wasnt finished yet. In fact, Id grown so fast there were faint stretch marks on the backs of my knees.

I was tall and young, but still quite shy and introverted. My parents had noticed that I had started collecting American Vogue , and after watching the TV program it occurred to them that appearing in a fashion show at the local mall might help to boost my confidence. So one afternoon my mother took me to a local model agency, Charles Stuart. The reaction of the agent, Corey Paisley, was not at all what wed expected. He said I had something called It. He said I was just what they were looking for in Europe, and as soon as European casting agents saw me they would want me to fly to Milan and Paris to work. He urged us to sign a contract, and urged me to book in for a modelling test shoot immediately, so they could see how I looked on camera in makeup. It would cost us a lot of money to have the test shoot done, though, he warned.

Instead of agreeing right away, my mother played it safe. Surprised and a bit wary, she thanked the agent for his time and left without making any commitments. Thirty minutes later we were at the top of Mount Tolmie looking over the town I know so well. This was where I had grown up. I could name the streets below, I could see the houses of my friends, my high school, even the hospital where I was born. Id never been on an aeroplane, let alone to another continent. The only work Id done was a newspaper route with my friend Debbie, and delivering the local Penny Saver coupon flyer with my mom.

My mother hadnt been on a plane either. She had come to Canada by boat from Holland after World War II. Her father, my Opa, had been forced by the Nazis to work in a munitions factory in Berlin during the occupation, along with a lot of other young, able-bodied Dutch men. A baker by trade, he baked bread in the munitions oven to bribe the foreman, got a pass to leave the factory, then stole a horse and cart and galloped past the guards at the checkpoint. He freed the horse in a field and continued on foot, walking nearly 700 kilometres, mostly under cover of darkness, back to his hometown of Numansdorp, a small town south of Rotterdam. There he hid, emerging from the family home only at night, worrying every day that the Nazis would come after him for escaping the work camp. By the time the war was over, their village had been flooded twice and their house was shelled.