Throughout the main text I have silently corrected misspellings and printers errors. I have occasionally modernized a spelling. Punctuation has been standardized to American usage throughout.

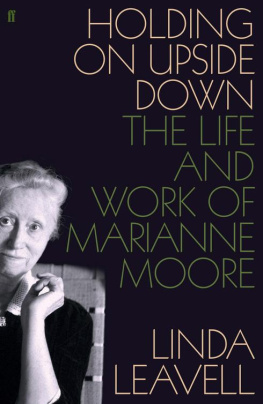

What should one call a new edition of Marianne Moores poetry? What

can one call it, given the titles of her books that have been or are currently in use? During her life there were books of her poems called

Poems (1921),

Selected Poems (1935),

Collected Poems (1951), and

Complete Poems (1967). After her death came a revised version of

Complete Poems (1981), and the

Poems of Marianne Moore (2003). Looking over this list a reader might wonder what is left to do with a body of work already selected, collected, and presented complete several times over. The answer is that selected is the only adjective that accurately describes any book of Moores work thus far produced, or any that can be produced. Moores art has no straight path from beginning to end; there is no vantage point from which one can see it whole.

She created new poems throughout her life, but she also created new arrangements of the old. At her direction major poems disappeared from print, early poems appeared in late collections, carefully planned series of poems were broken up and dispersed, and intricate stanzaic forms were truncated and left ragged as she revised her poems, sometimes out of all recognition. Even in an age known for poets who reshaped their own work, Moores revisions are unique in their sheer number and in the length of time over which she persisted in making them. For Moore, the publication of a poem in a periodical, or the ordering of poems in a book, marked resting-places in her poetrys development, not its final form. There is good reason to think that her own death is, in effect, only a particularly protracted pause in a process of revision that would otherwise have had no end. The complex, involuted textual history Moore left behind means that forty years after her death we have just begun to explore the ways her poems may be presented, and little about our view of her work as a poet is complete.

The outlines of her career, by contrast, are well known. She was born in 1887, in Kirkwood, Missouri. She and her brother, John Warner Moore (called Warner), were raised by their mother, Mary She began publishing her poems in student magazines during her undergraduate years at Bryn Mawr (19059) and continued to publish them until her death in 1972. Moores poetic maturity coincided with that of American Modernism, a movement in which she was a defining figure. Her poems appeared in its journals, both radical and established, and for four years, between 1925 and 1929, she edited the Dial, the most prestigious literary journal of its day. Her decisions in that role, about what to publish and from whom to solicit work, along with the hundreds of commentary pieces and book reviews she wrote, meant that her ideas directly shaped the literary landscape in which she and her peers worked.

Among her friends, correspondents, and colleagues were Robert Frost, T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, H.D., Mina Loy, William Carlos Williams, and Langston Hughes. The next generation consciously challenged and enriched by her work includes John Ashbery, Elizabeth Bishop, Louise Bogan, Robert Duncan, James Merrill, Lorine Niedecker, May Swenson, and countless others.

In the later decades of her life she had a career as a more popular public figure as well. In 1955 the Ford Motor Company invited her to suggest names for their new model (she gave them more than forty suggestions, including Utopian Turtletop and Mongoose Civique; they declined all of them and named it the Edsel instead). In 1963 she contributed to the liner notes for Muhammad Alis (then Cassius Clays) spoken-word album I am the Greatest!, and in 1968 she threw the first pitch of the season at Yankee Stadium, a privilege usually reserved for presidents and Hollywood celebrities. That late fame is now largely forgotten, founded as it was on a protective persona Moore developed and then inhabited until the end of her life: Americas beloved, eccentric maiden aunt, costumed in tri-corn hat and cape. There are many arresting and engaging photographs of Moore from that time, but they depict an artist far removed from the young, ambitious, driven, and voraciously intellectual poet who mattered to her Modernist peers and matters to poets today. Moores private life was mismatched with the popular image of sexually free-wheeling and politically radical bohemian living in Greenwich Village of the 1920s.

Nevertheless, she was drawn early to New York as a center of experimental and progressive art. She first visited the city in 1909, documenting her sense of being bewitched, with pleasure (Letters, 55) and flourishing like a bay tree (Letters, 57) in a series of letters to her mother and brother. When Moore visited New York City again, in December 1915, she was an informed cultural explorer, visiting Alfred Stieglitzs gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue to see the latest in avant-garde art, and meeting the writers and editors who would become her friends and peers when she (and her mother) moved there for good in 1918. By 1925, having published several of her longest and best poems, and having assumed the editorship of the Dial, she was herself a writer and editor younger artists came to New York to meet. Ten years later, in 1935, T. S.

Eliot, an admirer of Moores work since he first published it in the London-based Egoist, edited and wrote an introductory essay for Moores Selected Poems. In this essay he articulates her value for him in definite terms: Miss Moores poems form part of the small body of durable poetry written in our time; of that small body of writings, among what passes for poetry, in which an original sensibility and alert intelligence and deep feeling have been engaged in maintaining the life of the English language. (xiv) Moores best readers have often been fellow poets, who, like Eliot, celebrate her artistry in uninflated, even technical terms. The precision of Moores poems taught her readers precision in their praise, as when William Carlos Williams writes Miss Moores [work] holds its bloom today by the aesthetic pleasure engendered when pure craftsmanship joins hard surfaces skillfully (Williams, 315). Williams calls her craftsmanship pure for some of the same reasons Eliot calls her sensibility original. Using the same materials as all others before her, Williams writes, [Moore] comes at it so effectively at a new angle as to throw out of fashion the classical conventional poetry to which one is used and puts her own and that about her in its place [T]here is a multiplication, a quickening, a burrowing through, a blasting aside, a dynamization, a flight over (Williams, 311).