Modernist Women Poets An Anthology  Copyright 2014 by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Modernist Women Poets : an anthology / edited by Robert Hass, Paul Ebenkamp. pages cm 1. American poetryWomen authors. 2.

Copyright 2014 by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Modernist Women Poets : an anthology / edited by Robert Hass, Paul Ebenkamp. pages cm 1. American poetryWomen authors. 2.

American poetry20th century. 3. Modernism (Literature) 4. WomenUnited States--poetry. I. II. II.

Ebenkamp, Paul, editor of compilation. PS589.M53 2014 811.50809287dc23 2013047445 ISBN 978-1-61902-382-6 Cover and interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Counterpoint Press 1919 Fifth Street Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents C.D. WRIGHT BORN NEAR THE END of the nineteenth century (with the exception of Laura Riding tipping a year into the twentieth), all sixteen of these poets, in one form or another, removed the stays from their corsets, as Gertrude Stein did immediately upon crossing the Atlantic, and emancipated their quick intelligences to make art. There is a defiant streak in all of them and they are as clear about what they oppose as they are that words are their weapons, utensils, and toys. Only one was born in the South and stayed rooted in her native state.

Only three of them had children. Five of them preferred women to men. Most traveled extensively or relocated far from their origins. Many of them lived long and calamitously and struggled with poverty, disease, divorce, and, in one instance, rape and likely incest. Two died very prematurely, one of tuberculosis and one of scarlet fever. Some were educated at private colleges for women: Bryn Mawr, Vassar, Radcliffe, and Sweetbriar.

There was a Berkeley and a Cornell graduate. Djuna Barnes barely attended school. Djuna Barnes was a prolific, free-ranging journalist. Marianne Moore taught Commercial English and law at a Native American school and was a part-time librarian; Anne Spencer was also a librarian. Hazel Hall labored at a sewing machine in the family attic. Within a wide span of intensity and yield, they all felt compelled to write poetry.

In order of their birth dates: Lola Ridges Hester Street (1910) in The Ghetto is as layered, vivid, and tense as Spike Lees street in Bedford-Stuyvesant on the hottest day of the year in Do the Right Thing (1989). Nomadic and urban, Ridge shifted often from country to country and early on from painting to poetry. Her political fire provided oxygen for her intellectual and creative expression. Gertrude Stein broke all of the rules and they would never support their old armchair authority again. The first freedom comes with having an independent income. The second, with leaving your country behind.

The next freedom comes with refusing to abide by the strictures of ones assigned gender. (It doesnt hurt to have an in-house amanuensis, reader, cook, host, and pillow partner.) The absence of children is further liberating. (It is more or less substantiated that offspring have been a contributing factor to many male artists leaving their familiesfrom Gauguin to Sherwood Anderson.) Mr. Anderson happens to have been Ms. Steins unlikely, unwavering advocate. It was his astute observation that she used words as if they had no experience: Ex, ex, ex.

Bull it bull it bull it bull it. Ex Ex Ex. And amid many simple nouns, not a one stranger than, say, cigarette; amid much sibilance, rollicking repetition, reams of wittily coded sexual pleasure, and what John Ashbery has referred to as that sudden inrush of clarity that is likely to be an aesthetic experience, Gertrude Stein reveals the true source of her optimistic output: In the midst of writing there is merriment. Amy Lowell took the imagist experiment to heart and found a way to compress much of what she experienced to color, liquid, light, and hard, smooth surfaces, only leaking her internal restlessness with an occasional disquietude, I alone am out of keeping. Dadaism offered a kind of haven for Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. It could not protect her from herself or the worlds arbitrary cruelties, but it could allow her some fun with her tongue, and she used it to lick and to lash.

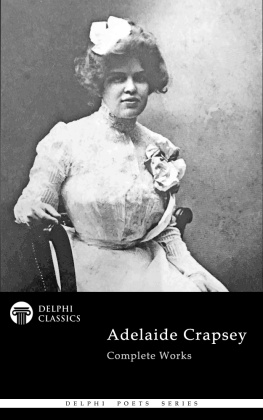

The everyday inanities of commerce and the urban hubbub went into her rowdy mash-up: Famous Fain reduces Reglar fellows to the Toughest Cory Chrome Pancake apparelkept Antiseptic with gold dust Rapid transit It has raised 3 generations Of mince-piston-rings-pie. Wake up your passengers Large and smallto ride On pinesdirty erasers and Knives Adelaide Crapsey was not afforded a long lifeline. She went to college, studied in Rome and taught at Smith, but mostly she watched the world from her Brooklyn window and kept a bracing seasonal vigil over her own dying. She applied an economy of words uncommon for her time coupled with a stoic yet revealing level of restraint. Like Stein, Angelina Weld Grimke was a lesbian, but she lived under her fathers roof and sacrificed her desires to his rules. Her mother had evidently been committed to an institution early in Ms.

Welds life. Poems provided an outlet both for racial and sexual repression. On the unhassled page she could reject the constricted status of African Americans and assert her love for other women. The child of former slaves, raised in foster care, Anne Spencer had a long, fruitful life as a teacher, wife and mother, librarian, vocal community activist, and prodigious gardener. Her home, garden, and the writing cottage her husband built for her in the garden are now a public museum in Lynchburg, Virginia. She wrote fearsome poems of protest such as White Things (unpublished in her lifetime), was much anthologized and had many literary friends in the center of the action of the Harlem Renaissance.

However, it was the landscape of Virginia and the private world of her garden on which she lavished symbolic meaning and tilled a simple language of satisfaction. In her mid-thirties by the time she moved to New York City from Paris, Mina Loy had already dropped out of art school. Traveled. Married badly. Had affairs. Divorced.

Lost a child. Left her two surviving children in someone elses care for a time. She had already been exposed to all of the currents of the art world and seemed to have some facility for everything that caught her attention. Her love poems (Songs to Joannes) are described by her biographer Carolyn Burke as a peculiar kind of war poetry, though critics tend to focus on the body as the centerfold of this sequence that is an audacious sendup of the romantic love poem. Bear in mind, this is writing that finds words delicious and will not have them chained to the wall of denotation. Being bourgeois was not her line of work.

Her famous poem Lunar Baedeker is, for the traveling reader, a near hallucinatory trip: Delirious Avenues / lit / with the chandelier souls / of infusoria / from Pharoahs tombstones, not to your next Best Western. Hazel Hall never escaped her thirties, her wheelchair or sewing machine. Hazel Hall, poet. Hazel Hall, seamstress. She made an art out of her laborsewing was one thing, writing about it another. And then there is death, the imminence of which she was well aware; that, too, became her artdying was one thing, writing about it another: Some who die escape The rhythm of their death, Some may die and know Death as a broken song, But a woman dies not so, not so; A womans death is long.

The elaborate embroidery at which she was adept is absent from the unadorned lines of her isolation. In the upper floor of her family home, like Adelaide Crapsey, she watched the world from her window. Adelaide Crapsey succumbed to tuberculosis and Hazel Hall to scarlet fever. H.D.s Sea Rosethe first poem in her first book,

Next page

Copyright 2014 by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Modernist Women Poets : an anthology / edited by Robert Hass, Paul Ebenkamp. pages cm 1. American poetryWomen authors. 2.

Copyright 2014 by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Modernist Women Poets : an anthology / edited by Robert Hass, Paul Ebenkamp. pages cm 1. American poetryWomen authors. 2.