To

FRANK PISKOR

Copyright

Copyright 1963 by Syracuse University Press.

Introduction copyright 2011 by Sara Davis Buechner.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

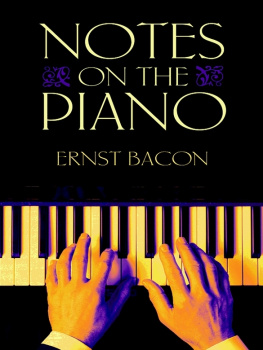

This Dover edition, first published in 2011, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Syracuse University Press in 1963. A new Introduction has been specially prepared by Sara Davis Buechner.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bacon, Ernst, 1898-1990.

Notes on the piano / Ernst Bacon; with a new introduction by Sara Davis Buechner.

p. cm.

This Dover edition, first published in 2011, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Syracuse University Press in 1963.

9780486310855

1. MusicQuotations, maxims, etc. 2. PianoInstruction and study. I. Buechner, Sara Davis, 1959- II. Title.

ML66.B23 2011

786.2dc23

2011017589

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

48366501

www.doverpublications.com

Introduction to the Dover Edition

The Artist should not forget his mission, perhaps the most religious of all, of sustaining faith in the worthwhileness of art and thus of life.

Ernst Bacon

The present volume found its way into the hands of this reader while still a teenage conservatory undergraduate, and rapidly became one of the most treasured books on my piano shelf. Although Notes on the Piano is ostensibly Ernst Bacons contribution to the pedagogic literature about classical piano playing, it is as unlike a book about daily scales and pedalling insights as, say, the philosopher Krishnamurtis meditations are unlike a self-help stress relief primer. Bacons open-ended approach to the vast literature, technique, interpretation and very ethos of the piano, its music and its connection to the creative heart, leads his lucky reader to a position not so much of conclusion, but to a renewed starting place of wide-eyed, continual learning, questioning, and discovery.

Ernst Bacon was born in Chicago on May 26, 1898, and showed early gifts in the manifold fields of music, art, poetry and mathematics. Early studies at Northwestern University and the Universities of Chicago and California were followed by two years of work in Europe. His teachers included Ernest Bloch for composition, Alexander Raab and Glenn Dillard Dunn for piano, and Eugene Goosens for conducting. Upon his return from Europe in the mid-1920s, Bacon began to make his name in many fields. He founded the Carmel Bach Festival in 1935, served as supervising conductor of the San Francisco Federal Music Project, and later became Dean of the School of Music at Converse College in Spartanburg, South Carolina, a position he held until 1945. For the next twenty years he made Syracuse University his base of operations, working there in succession as Professor of Piano and Director of the School of Music, and later as Composer-in-Residence. Upon his retirement in 1964, Bacon returned to his beloved California coast and continued to compose, virtually until the day he died on March 16, 1990 at the age of 91 in the town of Orinda, near Berkeley.

It was as a profoundly American composer that Bacon was most known during his lifetime, forging a proudly nationalistic path alongside his contemporaries Aaron Copland (b. 1900) and Roy Harris (b. 1898). Winner of the 1932 Pulitzer Prize in Composition for his Second Symphony and recipient of three Guggenheim Fellowships, he wrote copiously for orchestra, chamber ensemble, and piano Riolama (1963) for piano and orchestra, and two important folk operas in collaboration with Paul Horgan: A Tree on the Plains (1942) and Fords Theater (1946). American literature was perhaps dearest to Bacons heart, and it was in his numerous operas, oratorios, cantatas and especially song cyclesset to the poetry of Emily Dickinson, William Blake, Walt Whitman, Carl Sandburg, and other American mastersthat he combined his loves of melody, literature, and profoundly nationalistic spirit. Somewhat along the lines of the Hungarian Bla Bartk, he collected folk music of the American heartland. Appalachian songs, Southern spirituals, patriotic melodies, and cowboy tunes all figured in his original music and transcriptions, which he included in his own piano anthologies Along Unpaved Roads: Songs of a Lonesome People, Byways, and Maple Sugaring, as well as in collations of pedagogic childrens pieces.

Bacons cosmopolitan thirst and Renaissance nature led him to comradeship with the poet Carl Sandburg, African-American lyric tenor Roland Hayes, playwright Thornton Wilder, journalists Herb Caen and H. L. Mencken, and countless other leading American cultural figures. But the most significant of his artistic friendships was with the environmentalist photographer Ansel Adams (19021984). Their shared love of music was buttressed by a profound respect for nature and enthusiasm for mountaineering. Soon after Adams passing in 1985, Bacon memorialized his friend in the moving elegy for solo clarinet, timpani, and string orchestra, Remembering Ansel Adams (1985).

Ernst Bacons output as a writer was, if necessarily smaller than his work as a composer, scarcely less distinguished in quality. At the tender age of 19 he wrote his musical treatise, Our Musical Idiom (1917) in which he explored some of the new harmonies of the post-tonal age. While at Converse College he served as music critic for its weekly newspaper, The Argonaut, and he remained an avid contributor to magazines and University reviews throughout his life. In addition to his later volumes, Notes on the Piano (1963) and Words on Music (1966) he left many unpublished manuscripts and poems upon his death.

The magic of Notes on the Piano lies in its unique and enchanting presentation of the material. As Bacon states at the outset, this is a book to be nibbled ... its thought is not successive nor cumulative. Its last chapter could as well be its first. The book takes the form of statements, phrases, aphorisms, and short essays. The overall format presents itself in five parts, loosely arranged according to a subjective subdivision of the pianists musical rolesas student, performer, listener, and commentator. Some of the observations of one chapter overlap with another. But any preliminary assumption by the reader that Bacons essays are wholly improvisatory is mistaken, and one can imagine a twinkle in the authors eye as he wrote that opening pithy salvo, clearly meant as a come-on to the reader to dive in. Although it is true that the book can be delightfully sampled, dipped into as with a ladle into a punchbowl of refreshing iced Sangria, it is perhaps best savored slowly through the voyage from first page to last.

There is indeed method to Bacons thoughts, and the pattern of subject matter leads the reader on a rewarding journey that is not unlike the discoveries a pianist makes in learning a new work of, say, Beethoven or Schumann. The opening three chapters pose many of the questions often faced by an interpreter upon digesting a new musical score. How to proceed? What is the correct tempo? Whats this melody all about? Then, in the next trio of chapters one is plunged into the Musical Woodshed (otherwise known to pianists as the Practice Room). Now its time for the nitty-gritty: technical questions of which fingers to use, how to hold the arms, control of contrapuntal lines, understanding the composers style. In one fascinating and particularly useful section, Bacon opines on the concept of how equality of fingerwork can be effected by the practice of symmetrical mirror scales, a keyboard technique particularly beloved of 20th-century composers Vincent Persichetti (a friend of Bacons) and Einojuhani Rautavaara.

Next page