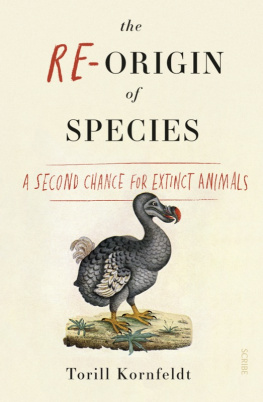

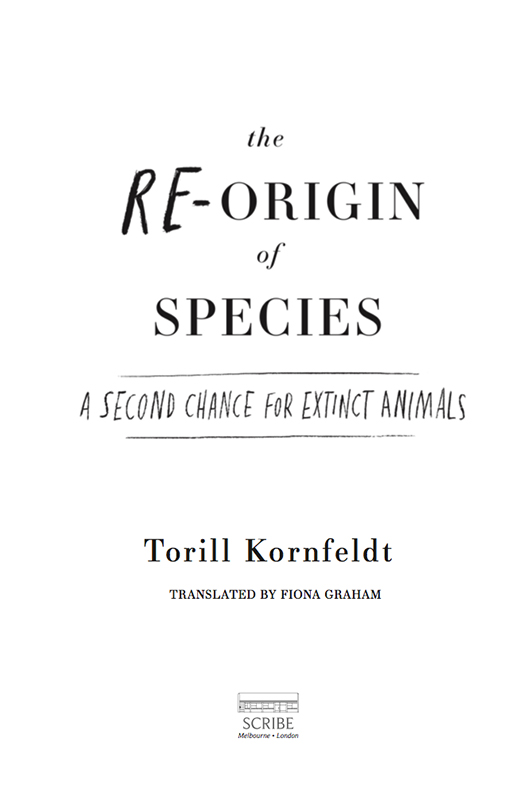

THE RE-ORIGIN OF SPECIES

Torill Kornfeldt is a Swedish science journalist with a background in biology. She has worked for Swedens leading morning newspaper, Dagens Nyheter , and for the Sveriges Radio public broadcaster, where she created the successful radio show Tekniksafari . Her focus is on how emerging bioengineering and technology will shape our future. The Re-Origin of Species is her first book.

Scribe Publications

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John Street, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

Originally published as Mammutens terkomst in Swedish by Fri Tanke Frlag, Sweden in 2016

First published in English by Scribe in 2018

Published by agreement with the Kontext Agency

Text copyright Torill Kornfeldt 2016

Translation copyright Fiona Graham 2018

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted.

9781925713060 (ANZ edition)

9781911617228 (UK edition)

9781947534360 (US edition)

9781925693003 (e-book)

CiP data records for this title are available from the National Library of Australia and the British Library.

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

for

Tobias, Torgny, and Ruth-Aime

TRANSLATORS NOTE

The passages quoting those scientists who were interviewed in English are not verbatim transcriptions. In many cases, they are a compressed or summarised representation of what the interviewees said, based sometimes on sound recordings and sometimes on written notes. It was not possible to have access to all of this material.

CONTENTS

Introduction:

Conclusion:

INTRODUCTION

A Whole New World

Greek mythology tells the tale of Prometheus, who defied the gods to bring humankind the knowledge of fire and how to use it. Prometheus was harshly punished by Zeus, yet the Greeks regarded fire as the source of all art and science. This narrative resembles the Biblical Fall; while the fruit of knowledge comes at a high price, it is a precondition for becoming fully human.

A couple of thousand years later, in 1818, Mary Shelley published her novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus . The story showed what might happen if human pride and ambition overreached themselves in a bid to emulate God. At the time the book was written, scientists had just discovered that they could make a dead frog twitch by delivering jolts of electricity to the corpse. There were theories that a divine, life-giving force might have been discovered. Taking inspiration from Jewish legends about golems, Mary Shelley created a terrifying scenario in which a scientist applied that force without really comprehending or being able to control it. For the book is also the story of a scientist who refuses to accept responsibility for his work a man who flees, leaving the newly awakened monster to his fate. Its clear that if Victor Frankenstein had had the courage to stay and take care of his creature, tragedy could have been averted.

One hundred and seventy-five years later, in 1993, the film Jurassic Park showed resurrected dinosaurs running amok because scientists had let their enthusiasm and curiosity get the better of them. The moral that revolutionary knowledge and godlike powers can cost us dear has been thoroughly rammed home. At the same time, the idea persists that we would no longer be human if we lacked that very drive.

It may sound silly to let yourself be influenced by ancient myths today, yet I believe these stories were the reason for my mixed feelings when I heard that scientists were working towards resurrecting extinct animals with the help of modern gene technology.

My first reaction was one of boundless enthusiasm. I felt like an excited ten-year-old at the thought of being able to see a real live mammoth, or a dinosaur, or any of the creatures that have died out in the course of history at the idea of actually seeing them move and hearing the sounds they made. What does a mammoth smell like? Do dinosaurs bob their heads as they walk, like todays birds? Do aurochs low like cows?

Scientists are also trying to restore many less spectacular creatures that are at least equally fascinating. The Australian gastric-brooding frog is one example. The female frog would eat her eggs and let them develop from frogspawn into baby frogs inside her belly. Then she would regurgitate a litter of croaking froglets ready to meet the world. This genus died out in the 1980s, struck by a fungal disease that continues to threaten many other types of frog. The project to resurrect the gastric-brooding frog has been dubbed Lazarus, after the story of how Jesus brought a man back from the dead.

All the projects I describe in this book began with the thought: Wow! We could actually do this. Of course well give it a try! They are driven by the same enthusiasm and curiosity that makes a child learn the name of every dinosaur that ever walked the earth, or an explorer set sail for the distant horizon. Its easy to be swept along and to feel the same effervescent energy.

My second feeling was one of age-old unease. Is this really a good idea? What if it has unforeseen negative consequences? Would it mean unleashing forces that we would later be unable to control? This unease is not born of mythology alone. Theres no shortage of examples of well-intentioned people who have wreaked havoc on the natural world.

One example absurd from todays perspective, but a good illustration is afforded by Eugene Schieffelin, an American who began releasing European birds in New York in 1890. His aim was to make sure that every single type of bird mentioned in the works of Shakespeare was represented in the United States. Schieffelin was a member of a highly respected scientific association, and his project enjoyed widespread support. It was associated with the acclimatisation movement, which actively dispersed species from continent to continent.

While most of the species died out within just a few years, the hundred starlings released in Central Park multiplied rapidly. They displaced large numbers of native birds as they spread out over the continent. Today, the United States has about 200 million European starlings, creating problems both for the ecosystem and for farming. And all this sprang from the worthiest of aims biological and cultural enrichment.

Each day as a science journalist brings me examples of how scientific curiosity and zeal are improving life for almost all human beings. These range from the technology we use to the medicines we take, the food we eat and the clothes we wear. I am genuinely convinced that the world is getting better all the time, and that the main reason for this is new research. And yet for all my optimism and confidence in the future that uneasy feeling in my stomach persists.

Gene technology and biotechnology are developing at the same rate today as information technology did in the 1990s, possibly even faster. This means scientists can already do things considered impossible just a few years ago. It also means they will very soon be able to achieve things that seem impossible today. Recreating the mammoth may be one example.

New methods for restructuring genetic material in everything from bacteria to human beings have created a whole new world of opportunities, but also of fears. This potential seems all the more terrifying because of its novelty. Just as with the advent of computers, we lack a context for this development that could help us understand it and predict where it will lead.

Next page