CONTENTS

First U.S. edition

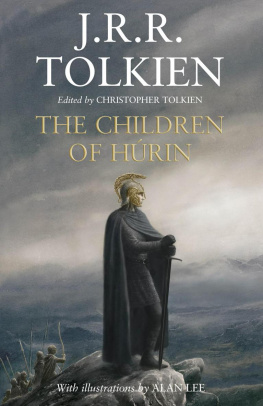

All texts and materials by J.R.R. Tolkien The Tolkien Estate Limited 2018

Preface, Notes and all other materials C.R. Tolkien 2018

Illustrations Alan Lee 2018

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhco.com

and Tolkien, Fall of Gondolin are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

and Tolkien, Fall of Gondolin are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Library of Congress Catologing-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-328-61304-2

e ISBN : 9781328612991

v1.0818

To my family

PLATES

They attempt to seize the swan-ships in Swanhaven, and a fight ensues (p.32)

he caused the watch and ward to be thrice strengthened at all points (p.64)

the tower leapt into a flame and in a stab of fire it fell (p.96)

that Balrog that was with the rearward foe leapt with great might on certain lofty rocks (p.107)

he should be led to a river-course that flowed underground through which a turbulent water ran at last into the western sea (p.135)

he saw a line of great hills that barred his way, marching westward until they ended in a tall mountain (p.160)

Then there was a noise of thunder, and lightning flared over the sea (p.167)

Tuor saw that the way was barred by a great wall built across the ravine (p.195)

PREFACE

In my preface to Beren and Lthien I remarked that in my ninety-third year this is (presumptively) the last book in the long series of editions of my fathers writings. I used the word presumptively because at that time I thought hazily of treating in the same way as Beren and Lthien the third of my fathers Great Tales, The Fall of Gondolin. But I thought this very improbable, and I presumed therefore that Beren and Lthien would be my last. The presumption proved wrong, however, and I must now say that in my ninety-fourth year The Fall of Gondolin is (indubitably) the last.

In this book one sees, from the complex narrative of many strands in various texts, how Middle-earth moved towards the end of the First Age, and how my fathers perception of this history that he had conceived unfolded through long years until at last, in what was to be its finest form, it foundered.

The story of Middle-earth in the Elder Days was always a shifting structure. My History of that age, so long and complex as it is, owes its length and complexity to this endless welling up: a new portrayal, a new motive, a new name, above all new associations. My father, as the Maker, ponders the large history, and as he writes he becomes aware of a new element that has entered the story. I will illustrate this by a very brief but notable example, which may stand for many. An essential feature of the story of the Fall of Gondolin was the journey that the Man, Tuor, undertook with his companion Voronw to find the Hidden Elvish City of Gondolin. My father told of this very briefly in the original Tale, without any noteworthy event, indeed no event at all; but in the final version, in which the journey was much elaborated, one morning out in the wilderness they heard a cry in the woods. We might almost say, he heard a cry in the woods, sudden and unexpected. A tall man clothed in black and holding a long black sword then appeared and came towards them, calling out a name as if he were searching for one who was lost. But without any speech he passed them by.

Tuor and Voronw knew nothing to explain this extraordinary sight; but the Maker of the history knows very well who he was. He was none other than the far-famed Trin Turambar, who was the first cousin of Tuor, and he was fleeing from the ruin unknown to Tuor and Voronw of the city of Nargothrond. Here is a breath of one of the great stories of Middle-earth. Trins flight from Nargothrond is told in The Children of Hrin (my edition, pp.1801), but with no mention of this meeting, unknown to either of those kinsmen, and never repeated.

To illustrate the transformations that took place as time passed nothing is more striking than the portrayal of the god Ulmo as originally seen, sitting among the reeds and making music at twilight by the river Sirion, but many years later the lord of all the waters of the world rises out of the great storm of the sea at Vinyamar. Ulmo does indeed stand at the centre of the great myth. With Valinor largely opposed to him, the great God nonetheless mysteriously achieves his end.

Looking back over my work, now concluded after some forty years, I believe that my underlying purpose was at least in part to try to give more prominence to the nature of The Silmarillion and its vital existence in relation to The Lord of the Rings thinking of it rather as the First Age of my fathers world of Middle-earth and Valinor.

There was indeed The Silmarillion that I published in 1977, but this was composed, one might even say contrived to produce narrative coherence, many years after The Lord of the Rings. It could seem isolated, as it were, this large work in a lofty style, supposedly descending from a very remote past, with little of the power and immediacy of The Lord of the Rings. This was no doubt inescapable, in the form in which I undertook it, for the narrative of the First Age was of a radically different literary and imaginative nature. Nevertheless, I knew that long before, when The Lord of the Rings was finished but well before its publication, my father had expressed a deep wish and conviction that the First Age and the Third Age (the world of The Lord of the Rings) should be treated, and published, as elements, or parts, of the same work.

In the chapter of this book, The Evolution of the Story, I have printed parts of a long and very revealing letter that he wrote to his publisher, Sir Stanley Unwin, in February 1950, very soon after the actual writing of The Lord of the Rings had reached its end, in which he unburdened his mind on this matter. At that time he portrayed himself self-mockingly as horrified when he contemplated this impracticable monster of some six hundred thousand words the more especially when the publishers were expecting what they had demanded, a sequel to The Hobbit, while this new book (he said) was really a sequel to The Silmarillion.

He never modified his opinion. He even wrote of The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings as one long Saga of the Jewels and the Rings. He held out against the separate publication of either work on those grounds. But in the end he was defeated, as will be seen in The Evolution of the Story, recognizing that there was no hope that his wish would be granted: and he consented to the publication of The Lord of the Rings alone.

After the publication of The Silmarillion I turned to an investigation, lasting many years, of the entire collection of manuscripts that he had left to me. In The History of Middle-earth I restricted myself as a general principle to drive the horses abreast, so to speak: not story by story through the years in their own paths, but rather the whole narrative movement as it evolved through the years. As I observed in the foreword to the first volume of the

and Tolkien, Fall of Gondolin are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited

and Tolkien, Fall of Gondolin are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited