Wed rather have the iceberg than the ship, although it meant the end of travel.

We had better begin with the question asked by every reader of the standard accounts of the great expeditions, the urgent question that floats irresistibly to the surface of ones mind as the contrast grows stronger and stronger between the safe, sensible surroundings in which one is reading, and the scenes that are being described. It works like a charm, always. One is sitting down somewhere in the warm perhaps it is sunny, perhaps it is a dark evening of a temperate winter and the radiators are on and whatever ones attitude, whatever the scepticism one applies to the boyish, adventurous text in ones hands, into ones mind come potent pictures of a place that is definitively elsewhere, so far away in fact that one would call it unimaginable if one were not at that moment imagining it at full force. Perhaps the place is a howling trough between two huge waves of the Antarctic Ocean, where a twelve-foot open boat encrusted with ice and containing five men, one of whom has gone mad and wont move, looks as if it is about to founder. Perhaps the place is the foot of a cliff in the dark, so cold and still that the breath of the travellers crystallises and falls to the snow in showers, so cold that their clothes will freeze at impossible angles if they do not keep their limbs moving. Perhaps the place is the South Pole itself, an abomination of desolation, a perfect nullity of a landscape, where a party of people are standing in a formal group, one pulling a string attached to a camera shutter. One is there in imagination as one reads, but with the possibility of instant withdrawal; one feels for the human figures at the centre of the scene, but one is not exactly in sympathy with them, though it is through their eyes that one is seeing. Their presence is as astonishing as their astonishing surroundings, something to be wondered at. And one asks, of course, everyone asks, why? Why did they do these insane things?

Another scene, not famous, not potent, requiring to be searched for. The beige and cream, rattan and mosquito netting of the Base Hospital, Delhi, in February 1910; despite the best efforts of the staff, a little dust spangling the strong Indian sunlight that projects in blocks and bars through chinks in the shuttered windows. The lights like something solid. Sitting up in bed in his pyjamas, Captain Laurence Edward Grace Oates of the Inniskilling Dragoons, who will be staggering out into a blizzard in two years time, is writing a letter to his mother on paper tiger-striped by sun and shade. Do not let the above address frighten you, I have merely drifted in here after eating a bad tin of fish on manoeuvres Scratch, scratch goes Oates pen, which he holds like a schoolboy. He has just heard that he has almost certainly been accepted for Scotts expedition to the Antarctic Points in favour of going. It will help me professionally as in the army if they want a man to wash labels off bottles they would sooner employ a man who had been to the North Pole than one who had only got as far as the Mile End Road. The job is most suitable to my tastes. Scott is almost certain to get to the Pole and it is something to say you were with the first party. The climate is very healthy although inclined to be cold

But then explorers are notoriously bad at saying why. Or perhaps they are notoriously good at avoiding giving a satisfactory answer. They laugh at themselves, they deplore the sensationalising of their expeditions, they say it all made sense at the time, they write books filled with practical detail which make readers ask why again. They decline to answer in terms that match a question arising as this one does. Maybe then the question is impossible, less of a real question than a gesture that a reader must make. It may be that no answer is really expected, that the question does all it is intended to do by registering astonishment, and signalling the difference between sensible us and mad them.

Sometimes that difference seems so wide that the histories of Antarctic exploration by the British in the heroic age might as well be myths. Although it is easy to list and date the major expeditions Scotts Discovery expedition, 19014; Shackleton in Nimrod, 19079; Scott in TerraNova, 191013; Shackleton in Endurance, 191416 they can seem to shed their identifying marks of period as we read about them. The guy ropes tying them to their time snap, and they float free, into a strange region of uncalendared events. The explorers still have Edwardian moustaches, Edwardian attitudes, Edwardian pasts in the cavalry or the Navy, but they appear to possess these things as purely personal characteristics, out of time and out of society, in a world peopled only by themselves. Whats more, that world at least as we experience it through print is at times even structured like the world of myth, of legend, of moral tales. As it is often told, the story of Scotts last expedition divides cleanly into three parts. What more natural, when woodcutters always have three sons, when the third key always opens the secret box? The story begins with a perilous journey: the expedition ship TerraNova, terribly overladen, flying the burgee of the Royal Yacht Club because it is too unseaworthy to carry the White Ensign, fights its way down through the mountainous waves of the Roaring Forties, almost sinking, until it reaches the shelter of the true South, where pack-ice calms the sea. Then there is the period of preparation, of loin-girding, of feats of arms: the explorers work in their hut by the hiss of gas-lamps through the long darkness of the Antarctic winter, readying equipment and sallying out on preparatory journeys. Finally there comes the climax, the resolution of the quest: the march on the pole, with the focus always narrowing as the supporting parties drop away, mounting to the magnified gestures and conclusive speeches of the disaster. This pattern is as satisfying as it always is. No tree decorates the bleakness of the landscapes, but the story clearly takes place on the traditional terrain of the magic wood, from which this time the trail of breadcrumbs does not lead the travellers back to safety.

Perhaps this is why the stories have survived, why they have the power to cross the decades and still work for people very remote from the dead explorers. It is not at all certain that we would like them, if we were able to meet them off the page, away from the clinching immediacy of myth. Theres a passage in OurMutualFriend where Dickens describes a group of Thames watermen fishing a body out of the river. They despise Rogue Riderhood, the apparent corpse, but they try to revive him. No one has the least regard for the man: with them all, he has been an object of avoidance, suspicion, and aversion; but the spark of life within him is curiously separable from himself now, and they have a deep interest in it, probably because it is life, and they are living and must die We probably do not find ourselves repelled by the explorers. On the other hand it is not necessarily because we feel much personal affinity with them that we are drawn in so intensely. The deep interest of those who are living and must die is the permanent source for the effectiveness of myth. We die along with Scott and Oates and the others on the return from the pole; then we find that we have survived the experience. So it touches fundamentals.

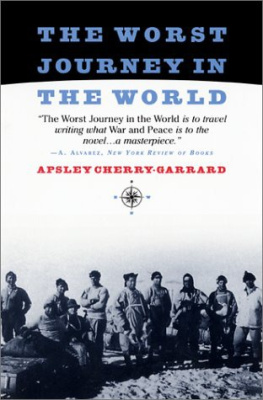

And the stories do survive; Scotts story in particular survives. Like any successful myth, it provides a skeleton ready to be dressed over and over in the different flesh different decades feel to be appropriate. It has changed many times over in the course of its transmission from 1913 to the present. In the postwar anomie of the 1920s, Apsley Cherry-Garrard published his memoir of the expedition,