Further praise for Backroom Boys:

Few books have begun to explain the profound changes that Britain has experienced in the past thirty years; this is an enjoyable and illuminating exception [Spuffords] six forensically researched and grippingly told tales of our times argue against the idea that when the factories and pits and shipyards closed, so did a certain kind of national self-ideal: that of home-made ingenuity and understated scientific brilliance. Observer

This is the most fascinating book Ive read all year The author Francis Spufford has a marvellous combination of gifts a deep passion for his subject, an engaging way with prose and a wonderful ability to explain elaborate concepts without erring into triviality. Daily Mail

Spufford writes with great verve and great skill The style is reminiscent of Tom Wolfes classic The Right Stuff. Spectator

Inspiring stuff This is first-class writing about the work of the scientists and technologists popularly supposed to wear pullovers and quizzical expressions, smoke pipes and do something incomprehensible in small back rooms. New Scientist

Terrific, an unlikely but compelling tribute to unsung ingenuity, as elegantly composed as the computer code it describes The reader will share [Spuffords] delight in settling down next to a roaring fire with these men and discovering that they do indeed wear jumpers and talk of colleagues as chaps. Financial Times

With Backroom Boys, Spufford has claimed an unlikely niche as the Bruce Chatwin of applied science. The Times

Spuffords wonderful Backroom Boys a celebration of post-war British engineering which, like all the best pop-science, seeks not just to heal any lingering Two Cultures rift, but to promote a broader understanding of what Spufford calls the shared material world we inhabit. Time Out

In memory of my grandfather, L. M. Clark, Sc. D 18971953

Industrial chemist

Contents

Kings, warriors, and statesmen have heretofore monopolised not only the pages of history, but almost those of biography. Surely some niche ought to be found for the Mechanic, without whose labour and skill society, as it is, could not exist. I do not begrudge destructive heroes their fame, but the constructive ones ought not to be forgotten; and there IS a heroism of skill and toil belonging to the latter class, worthy of as grateful record, less perilous and romantic, it may be, than that of the other, but not less full of the results of human energy, bravery, and character.

Samuel Smiles, Industrial Biography, 1863

The backroom boys is a phrase from the 1940s. Its what industrial-age Britain used to call the ingenious engineers who occupied the draughty buildings at the edge of factory grounds and invented the technologies of the future. Almost always, they were boys, or rather men: for historical reasons, but also because there is perhaps an affinity between the narrow-focused, wordless concentration required for engineering and a particular kind of male mind. Black-and-white war films made them iconic, gave them a public face everybody recognised, as the unworldly innocents who somehow produced a stream of spectacularly lethal gadgets. The backroom boys have come up with this. Perhaps youd like to explain, Dr Prendergast. Certainly, Major. You twist this little dial here, breaking the mercury-fulminate fuse, and you gently lower this lever here, and a sheet of flame comes out there. Oh, I am sorry. Im sure your moustache will grow back. In the cinema, real backroom boys like Barnes Wallis, creator of the bouncing bomb, and R. J. Mitchell, designer of the Spitfire, were joined by a legion of fictional counterparts. The public learned a set of characteristics that apparently spelled boffin: distracted demeanour, ineptitude at human relationships, perpetual surprise at the use that other people put their ideas to. But the backroom boys didnt only do military technology. They existed in every industry. They worked on the chemistry of paint, they devised new relays for telephone exchanges, they improved the performance of knitting machines. They were the quiet makers, regarded with affectionate incomprehension (and a little condescension) by a nation which found it easier to admire its smooth talkers and nice movers.

This book begins in the 1940s, but it is about much more recent British history. It is about what happened to the backroom boys as the world of the aircraft factories and the steel mills faded. There is an expected story here, a story we all know already about decline and the diminishing of British ambitions, but like the stereotype of the backroom boys, that story gives a complacent pat to a process which was, in truth, much less predictable. Its true that there were errors, there were losses, there was a retreat from industrial competence out of all proportion with necessity. But there were unremembered victories as well as unforgotten failures. Above all, there was adaptation. When the old industries faltered in Britain, the ingenious spirit of the backroom boys survived. The urge to build the future detached itself from lathes and wind tunnels, and reappeared in the new technologies of software, gene sequencing and wireless communications. The backroom boys are with us still.

This book is about the makers, but its also about the making. Engineering, of any description, is an art of the possible. It happens at the junction between what is materially possible and what is humanly possible. Its course is shaped by the latest developments in the endless struggle to manipulate obdurate matter, and also by the agendas and priorities and resources and hopes and illusions of a society. Engineering is where science intersects with the way we live. So the fortunes of governments and businesses belong in its story; they have to be told too.

All the events described here really happened, but I am not trying to write the whole history of the transformation that took place in Britain over the last thirty years. I have not set out to be comprehensive, or final. I have chosen six incidents in the process, six scenes in a much larger drama. But, taken together, they tell one story: the story of how Britain stopped being an industrial society, and turned into something else.

In November 1944, a group of men met in a London pub. They were engulfed by the cosy gloom of that late-Victorian moment when the clock stopped on the style of British drinking places; with an extra layer to the gloom in this fifth year of the war, less cosy. Dinginess had settled in too. London was dog-eared, clapped-out, frankly grimy. Though Britain had not shaken off its usual inefficiencies at mass production, it had converted its economy to the needs of the war more completely than any other combatant. For five years there had been no new prams, trams, lawnmowers, streetlamps, paint or wallpaper, and it showed. All over the city things leaked, flapped, wobbled and smelt of cabbage. It was the metropole that Orwell would project forward in time as the London of 1984.

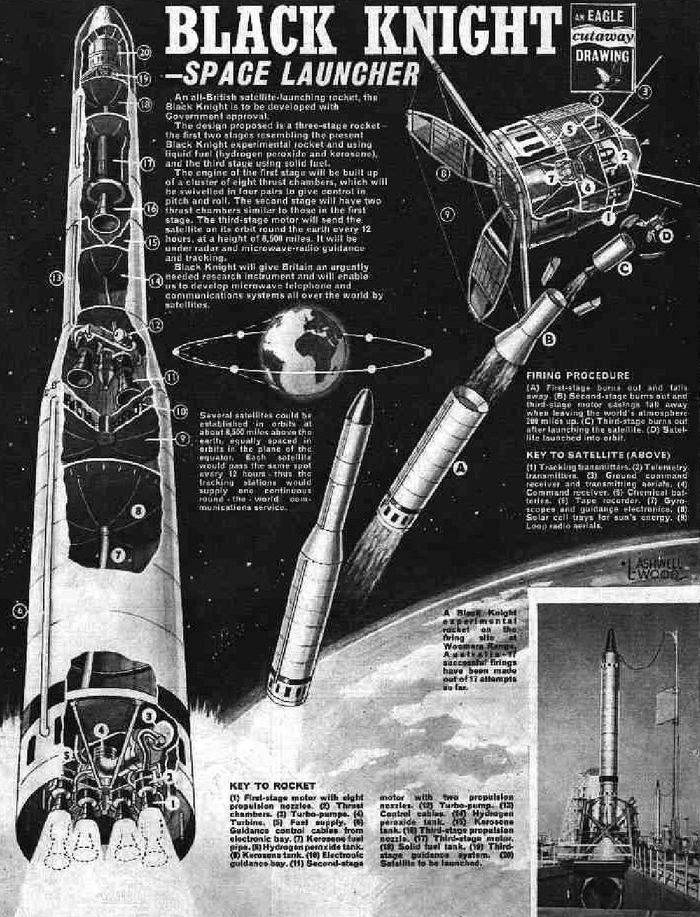

But these drinkers were not the kind of people to let an unpromising present determine the shape of things to come. They were the inner circle of the British Interplanetary Society, and in 1938 they had published a plan for reaching the moon using two modules, one to orbit, one to descend to the lunar surface. Since they calculated the plan might cost as much as a million pounds to carry out, they obviously could not build the rocket it called for. They could only have a go at a couple of the spacecrafts instruments. We were in the position of someone who could not afford a car, but had enough for the speedometer and the rear-view mirror, Arthur C. Clarke would remember later. So they constructed a coelostat, a device to stabilise the image of a spinning star-field. It was made from four mirrors and the motor of Clarkes gramophone; it worked, and it was proudly displayed in the Science Museum.