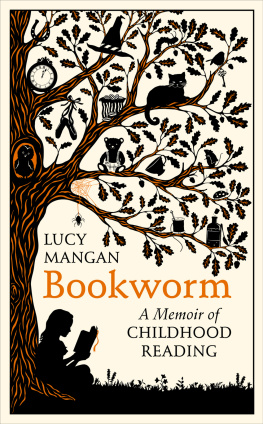

I can always tell when youre reading somewhere in the house, my mother used to say. Theres a special silence, a reading silence. I never heard it, this extra degree of hush that somehow travelled through walls and ceilings to announce that my seven-year-old self had become about as absent as a present person could be. The silence went both ways. As my concentration on the story in my hands took hold, all sounds faded away. My ears closed. I didnt imagine the process of the cut-off like a shutter dropping, or as a narrowing of the pink canals leading inside, each waxy cartilaginous passage irising tight like some deft alien doorway in Star Trek. It seemed more hydraulic than that. Deep in the mysterious ductwork an adjustment had taken place with the least possible actual movement, an adjustment chiefly of pressure. There was an airlock in there. It sealed to the outside so that it could open to the inside. The silence that fell on the noises of people and traffic and dogs allowed an inner door to open to the books data, its script of sound. There was a brief stage of transition in between, when Id hear the texts soundtrack poking through the fabric of the houses real murmur, like the moment of passage on the edge of sleep where your legs jerk as your mind switches over from instructing solid limbs to governing the phantom body which runs and dances in dreams. Then, flat on my front with my chin on my hands or curled in a chair like a prawn, Id be gone. I didnt hear doorbells ring, I didnt hear suppertime called, I didnt notice footsteps approaching of the adult whod come to retrieve me. They had to shout Francis! near my head or, laughing, Chocolate!

I laughed too. Reading catatonically wasnt something I chose to do, it just happened, and if it could be my funny characteristic in the family, a trademark oddity my parents were affectionate towards, that was great. Though I never framed the thought on the surface of my mind, stopping my ears with fiction was non-negotiable. There were things to block out. My parents were loquacious like me, constant reassurers, constant interrupters. Swags of talk flowed out of them like those many-folded banners used in medieval pictures, ancestors of the speech bubble. I idolised them and I wanted them to shut up. My little sister had kidney failure and trailed plastic tubes; I loved my ill sister and felt that I owed such a lot of attention to her state that I had better pay none. So treating the way I read jokily got us all off the hook. With an unspoken whew of relief it domesticated what was obviously a bit too extreme for comfort.

I still do it, still automatically wrap in humour my sludgy dives into text. I realised recently that in bookshops I do a placatory dumbshow as I move among the shelves. Ive got a little repertoire designed to make my reactions to the books Im cruising among likeable, likeable to an imaginary audience. Here I go, then: Im in the basement of a big science-fiction bookshop in central London, jinking left and right past posters of Princess Leia, Dr Who videos, Bart Simpson T-shirts, leather-fetish magazines mixed up in a rack with the Fortean Times, past science fictions outworks of non-verbal and semi-verbal stuff, towards its actual fiction, AZ by author. My business is there, and when it comes to books Im a really skilled browser, believe me, finely attuned to the obscure signals sent out by the spines of paperbacks, able to detect at speed the four or five titles in a bay that pull at me in different ways. Whats this? Imported American military SF, black gloss cover with display type of gothic spikiness, picture of space-opera interstellar dreadnought encrusted with guns on the front. Keyword mercenary in the blurb on the back, so itll be nasty; phrasing of the come-on lines also suggests post-Robert-Heinlein right-wing libertarian blow-up-Oklahoma-City mad gun-toting bullshit, not an uncommon ideological flavouring in this subgenre, so itll be programmatically nasty. I dont want to read this book, I certainly dont want to buy it, but I do want to take a single sip of its particular poison. Open a page at random. Oh my Lord, gushing human intestines. Very disgusting yet also kind of arresting. But now I want to put the book back, and as I slide it back into its neon nest I also want to push it away from me, from my tastes and the kind of person I am. I want to demonstrate that between a person like me and a book like that only an amused disdain is possible. So I do this thing. I pantomime furrowing my brow in pain; I draw back my lips from my teeth like an affronted chimp; I push air against my upper palate to make a hissy, glottal-stopped disgust-noise. Eekh! I say, as if eyes were fixed on me from all quarters as if the alacrity I now want to cancel might have been seen, like a spark arcing between eye and page, by other browsers, or the punks serving behind the counters who are often scholars of comic-book history, or the polite Asian heavies doing security on the door.

Actually, of course, I take it for granted that it hasnt. One of the first things you learn as you begin to read is the amazing exterior invisibility of all the rush of event and image which narrative pours through you. Im thirty-two years old as I do my little performance in the bookshop, which means Ive been reading for twenty-six years. Twenty-six years since the furze of black marks between the covers of The Hobbit grew lucid, and released a dragon. Twenty-six years therefore since the primary discovery that the dragon remained internal to me. Inside my head, Smaug hurtled, lava gold, scaly green. And nothing showed. Wars, jokes, torrents of faces would fill me from other books, as I read on, and none of that would show either. It made a kind of intangible shoplifting possible, I realised when I was eleven or so. If your memory was OK you could descend on a bookshop a big enough one so that the staff wouldnt hassle a browser and steal the contents of books by reading them. I drank down 1984 while loitering in the O section of the giant Heffers store in Cambridge. When I was full I carried the slopping vessel of my attention carefully out of the shop. Nobody at the cash desks could tell that I now contained Winston Smiths telescreen chanting its victories, OBriens voice admitting that the Thought Police got him a long time ago. It took me three successive Saturdays to steal the whole novel. But I have not ceased to be amazed at the invisibility I depend on. Other people cant see what so permeates me, I accept that, but why cant they? It fills me. The imbalance between whats felt and what shows means I carry the sensory load of fiction like a secret. Perhaps like all secrets it leaks in the end, but while Im still freshly distended with my cargo of images, while Im a fish tank with a new shoal in me, with one aspect of myself I enjoy the power of being different behind my unbetraying face. If I hung about stoned in front of a police station, solemn on the outside and spiralling chemically within, or wore a lace thong to the office beneath my business suit, I wouldnt be getting a different buzz. I flirt with discovery. My rigmarole in the SF bookshop is exhibitionism as well as defence, asks to be noticed while it tries to camouflage. Look at me! (Dont look at me!) Im cramming myself over here, Im gobbling worlds!

I need fiction. Im an addict. This is not a figure of speech. I dont quite read a novel a day, but I certainly read some of a novel every day, and usually some of several. There is always a heap of opened paperbacks face down near the bed, always something current on the kitchen table to reach for over coffee when I wake up. Colonies of prose have formed in the bathroom and in the dimness of the upstairs landing, so that I dont go without text even in the leftover spaces of the house where I spend least time. When Im tired and therefore indecisive, last thing at night, it can take half an hour to choose the book I am going to have with me while I brush my teeth. It always matters which book I pick up. I can be happy with an essay or a history if it interlaces like a narrative, if its author uses fact or impression to make a story-like sense, but fiction is king, fiction is the true stuff, compared to which non-fiction is a shadow, sometimes appealing for its shadiness and halfway status; only the endless multiplicity of fiction is a problem, in a life where reading time is still limited no matter how many commitments of work or friendship I am willing to ditch in favour of the pages.