He advised me to correct the rebellious principles I had imbibed among the English, who, for their insolence to their kings, were notorious all over the world.

I

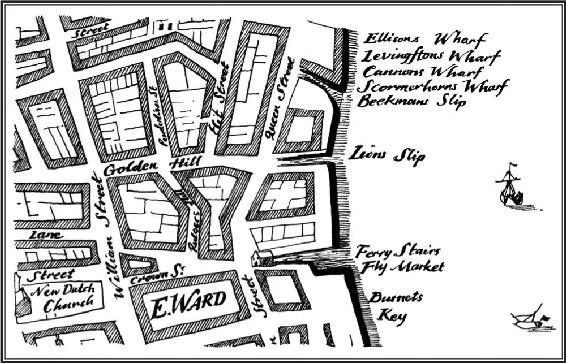

The brig Henrietta having made Sandy Hook a little before the dinner hour and having passed the Narrows about three oclock and then crawling to and fro, in a series of tacks infinitesimal enough to rival the calculus, across the grey sheet of the harbour of New-York until it seemed to Mr Smith, dancing from foot to foot upon deck, that the small mound of the city waiting there would hover ahead in the November gloom in perpetuity, never growing closer, to the smirk of Greek Zeno and the day being advanced to dusk by the time Henrietta at last lay anchored off Tietjes Slip, with the veritable gables of the citys veritable houses divided from him only by one hundred foot of water and the dusk moreover being as cold and damp and dim as November can afford, as if all the world were a quarto of grey paper dampened by drizzle until in danger of crumbling imminently to pap: all this being true, the master of the brig pressed upon him the virtue of sleeping this one further night aboard, and pursuing his shore business in the morning. (He meaning by the offer to signal his esteem, having found Mr Smith a pleasant companion during the slow weeks of the crossing.) But Smith would not have it. Smith, bowing and smiling, desired nothing but to be rowed to the dock. Smith, indeed, when once he had his shoes flat on the cobbles, took off at such speed despite the gambolling of his land-legs that he far out-paced the sailor dispatched to carry his trunk and must double back for it, and seizing it hoist it instanter on his own shoulder and gallop on, skidding over fish-guts and turnip leaves and cats entrails, and the other effluvium of the port asking for direction here, asking again there so that he appeared most nearly as a type of smiling whirlwind when he shouldered open the door just as it was about to be bolted for the evening of the counting-house of the firm of Lovell & Company, on Golden Hill Street, and laid down his burden while the prentices were lighting the lamps, and the clock on the wall showed one minute to five, and demanded, very civilly, speech that moment with Mr Lovell himself.

Im Lovell, said the merchant, rising from his place by the fire. His qualities in brief, to meet the needs of a first encounter: fifty years old; a spare body but a pouched and lumpish face, as if Nature had set to work upon the clay with knuckles; shrewd and anxious eyes; brown small-clothes; a bob-wig yellowed by tobacco smoke. Help ye?

Good day, said Mr Smith, for I am certain it is a good day, never mind the rain and the wind. And the darkness. Youll forgive the dizziness of the traveller, sir. I have the honour to present a bill drawn upon you by your London correspondents, Messrs Banyard and Hythe. And request the favour of its swift acceptance.

Could it not have waited for the morrow? said Lovell. Our hours for public business are over. Come back and replenish your purse at nine oclock. Though for any amount over ten pound sterling Ill ask you to wait out the week, cash money being scarce.

Ah, said Mr Smith. It is for a greater amount. A far greater. And I am come to you now, hot-foot from the cold sea, salt still on me, dirty as a dog fresh from a duck-pond, not for payment, but to do you the courtesy of long notice.

And he handed across a portfolio, which being opened revealed a paper cover clearly sealed in black wax with a B and an H. Lovell cracked it, his eyebrows already half-raised. He read, and they rose further.

Lord love us, he said. This is a bill for a thousand pound.

Yes, sir, said Mr Smith. A thousand pounds sterling; or as it says there, one thousand seven hundred and thirty-eight pounds, fifteen shillings and fourpence, New-York money. May I sit down?

Lovell ignored him. Jem, he said, fetch a lantern closer.

The clerk brought one of the fresh-lit candles in its chimney, and Lovell held the page up close to the hot glass; so close that Smith made a start as if to snatch it away, which Lovell reproved with an out-thrust arm; but he did not scorch the paper, only tilted it where the flame shone through and showed in paler lines the watermark of a mermaid.

Papers right, said the clerk.

The hand too, said Lovell. Benjamin Banyards own, Id say.

Yes, said Mr Smith, though his name was Barnaby Banyard when he sat in his office in Mincing Lane and wrote the bill for me. Come, now, gentlemen; do you think I found this on a street-corner?

Lovell surveyed him, clothes and hands and visage and speech, such as he had heard of it, and found nothing there that closed the question.

You might ha done, he said, for all I know. For I dont know you. What is this thing? And who are you?

What it seems to be. What I seem to be. A paper worth a thousand pounds; and a traveller who owns it.

Or a paper fit to wipe my arse, and a lying rogue. Yell have to do better than that. Ive done business with Banyards for twenty year, and settled with em for twenty year with bills on Kingston from my sugar traffic. Never this; never paper sent all on a sudden this side the water, asking money paid for the whole seasons account, almost, without a word, or a warning, or a by-your-leave. Ill ask again: who are you? Whats your business?

Well: in general, Mr Lovell, buying and selling. Going up and down in the world. Seeing what may turn to advantage; for which my thousand pounds may be requisite. But more specifically, Mr Lovell: the kind I choose not to share. The confidential kind.

You impudent pup, flirting your mangled scripture at me! Speak plain, or your precious paper goes in the fire.

You wont do that, said Smith.

Oh, wont I? You jumped enough a moment gone when I had it nigh the lamp. Speak, or it burns.

And your good name with it. Mr Lovell, this is the plain kernel of the matter: I asked at the Exchange for London merchants in good standing, joined to solid traders here, and your name rose up with Banyards, as an honourable pair, and they wrote the bill.

They never did before.

They have done now. And assured me you were good for it. Which I was glad to hear, for I paid cash down.

Cash down, repeated Lovell, flatly. He read out: At sixty days sight, pay this our second bill to Mr Richard Smith, for value received You say you paid in coin, then?

I did.

Of your own, or of anothers? As agent, or principal? To settle a score or to write a new one? To lay out in investments, or to piss away on furbelows and sateen weskits?

Just in coin, sir. Which spoke for itself, eloquently.

You not finding it convenient, no doubt, to move so great a weight of gold across the ocean.

Exactly.

Or else hoping to find a booby on the other side asd turn paper to gold for the asking.