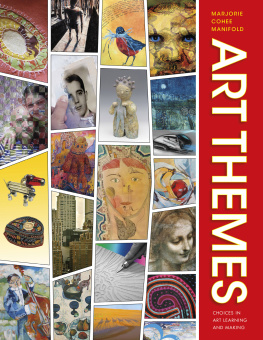

ART THEMES

ART THEMES

CHOICES IN ART LEARNING AND MAKING

MARJORIE COHEE MANIFOLD

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by Marjorie Manifold

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Manufactured in China

Names: Manifold, Marjorie Cohee, author.

Title: Art themes : choices in art learning and making / Marjorie Cohee Manifold.

Description: Bloomington, Indiana : Indiana University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017020278 | ISBN 9780253022929 (pr)

Subjects: LCSH: ArtTechnique.

Classification: LCC N7433 .M26 2017 | DDC 700dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020278

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18 17

Contents

ART THEMES

Introduction and How to Use This Book

This textbook is designed for those who are interested in art making for pleasure or who need to develop a few basic art making skills in order to achieve specific goals. The text introduces a variety of art themes, genres, materials, and processes that interest novice or casual art makers. Often those who have had little previous experience in art education assume that making artistic images and products requires a certain genetic disposition, or a talent bestowed at birth like a gift from a magical fairy godmother. Nothing could be further from the truth. All healthy human beings have a psychological need to express deep feelings and profound thoughts about the meaning of life in ways that go beyond words. We all seek to celebrate our loved ones and our belonging to community. We wonder about what came before us and what will remain when we are no longer conscious of life. We seek to mark transitions of joy and sorrow in our journey through life as an affirmation of our being. These needs are the foundations and motivations for creating in the arts.

James Ward (17691859), Arctic Dog, Facing Right, undated. Graphite on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, 6" 7" (17.15 18.4 cm). Paul Mellon Collection, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT.

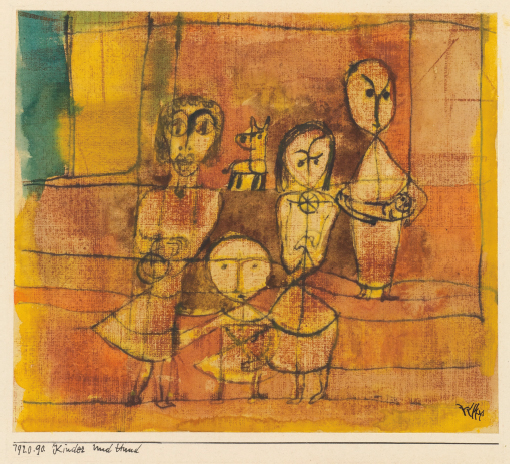

Another common misperception is that to be an artist one must be able to draw realistically. Yet because we all see life from differing perspectives and understandings, the notion of what constitutes realism is something of a moving target. For example, both of these artistic renderings are easily recognizable representations of a dog, yet neither looks exactly true to life. Each artist has simplified the texture, form, color, or lines that describe a dog; nevertheless, each image is realistic insofar as it conveys the idea of dog with clarity.

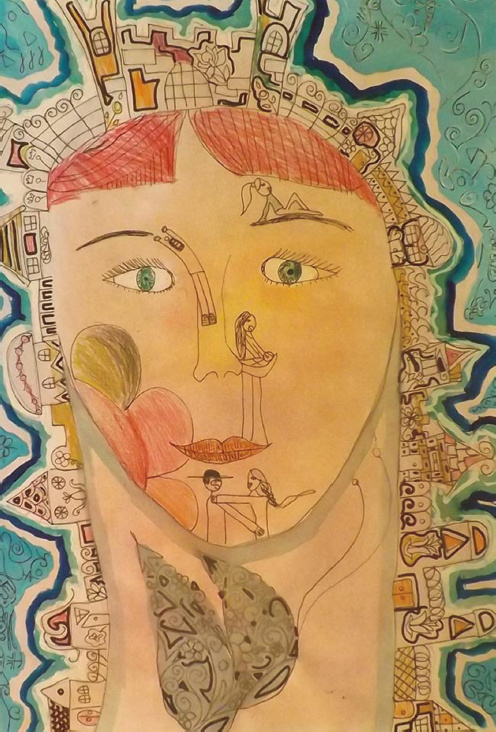

Young children tend to use drawing to symbolically communicate ideas that are not dependent on photographic realism. We may be familiar with stick-figure drawings of humans and recognize these to be the typically unsophisticated, albeit delightful, renderings by children. Yet many artists who seek to express tacit qualities of humanness have found that realism actually masks or challenges their abilities to describe such essences. Some have studied the works of children to rediscover how to communicate such ideas eloquently through symbols that could scarcely be called realistic.

Franz Marc (18801916), Dog Lying in the Snow, 1911. Oil on canvas. 24" 41" (62.5 105 cm). Stdel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany.

Of course, if you are using this text as a guide for learning to draw realistically, there are themes and lessons that can help you become more observant of what you see. This is crucial to drawing realistically. Additionally, there are physical tools and laws of science and mathematics that can be used to create impressive artworks. As you work through the lessons in this text, focus on what it is you wish to communicate and consider the most effective ways of visually presenting your feelings, thoughts, and ideas. In some cases, this may require that you practice techniques such as mathematically accurate depiction of aerial perspective or proportion, but there also are many ideas and experiences that can be articulated visually without relying on photorealism or great technical skills in realistic drawing.

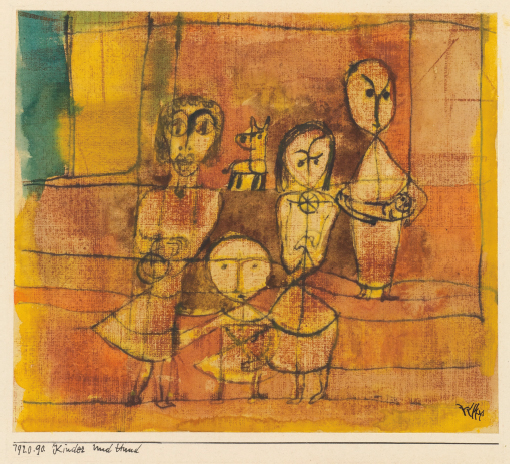

Paul Klee (18791940), Children and Dog (Kinder und Hund), 1920. Watercolor, pen, and ink on paper, 6" 7" (16.3 18.7 cm). Private Collection.

My hope is that through practice and experimentation with the lessons in this text, either working independently or guided by an instructor in an actual or virtual community of fellow learners, you will develop basic technical skills of art making and an enhanced ability to engage with ideas about art. Through exploring and completing one or several thematic units, you will also

experience pleasure experimenting with art making;

recognize your ability to replicate what is seen in a visually coherent way;

recognize your ability to communicate ideas coherently through visual symbols;

develop basic skills in a medium of choice;

recognize your ability to successfully make artworks that achieve personal goals;

be able to visualize how your personal art making might be useful or pleasurable to everyday life or in a future non-art-specific career.

Brian Cho, Gangham Station, 2015. Pencil on paper, 9" 12". (Courtesy of the Artist)

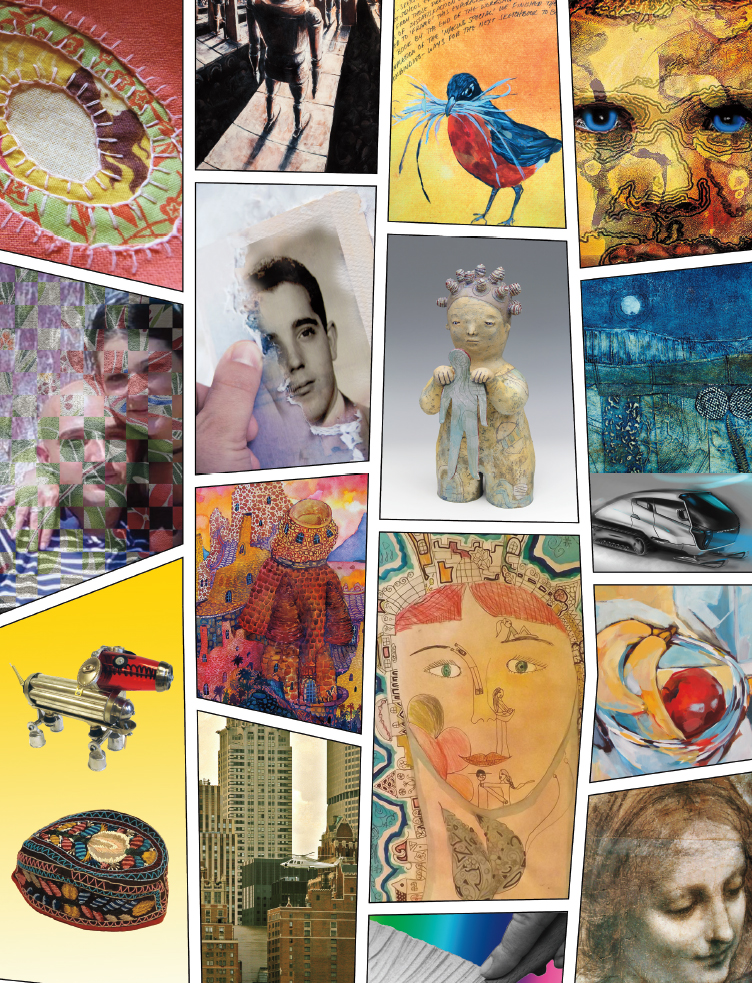

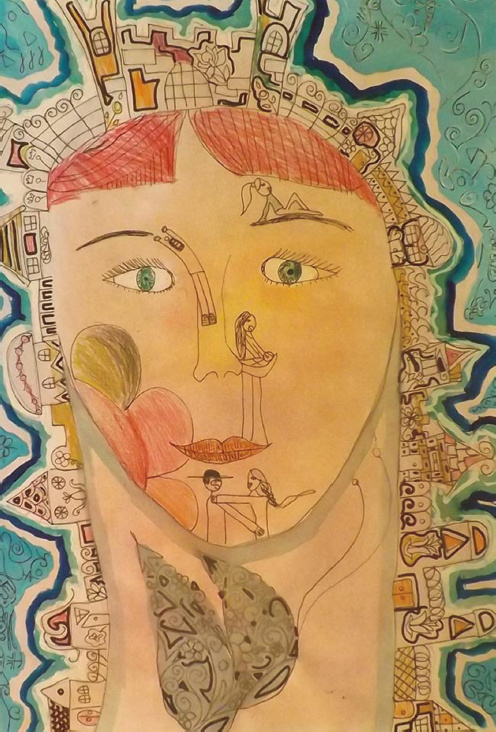

Anonymous, Portrait. Graphite and colored pencils, 18" 11". Created by a student of Ritk Nra, Director of Igazgyngy Alaptvny-Berettyjfalu, Hungary (Pearl Foundation Abu Dhabi), http://www.igazgyongy-alapitvany.hu.

Unlike many books that present art instruction in conventionally structured sequences, this text offers users numerous entry points for progressing through lessons. The hypertext-like organization of lessons is informed by observations of how art is learned in extracurricular settings among adolescents and adults of like-interested communities. Such observations tell us that art making is experienced more positively when individuals are allowed control in terms of thematic topics they choose to address, and are invited to make images or artifacts that are deemed useful, relevant to personal interests, important to future goals, or are in accord with hobbies in which they already engage. People who voluntarily create art also tell us they like to learn in holistic ways, obtain information and advice on a need to know basis, and receive affirmative support from peers and instructors.

Next page