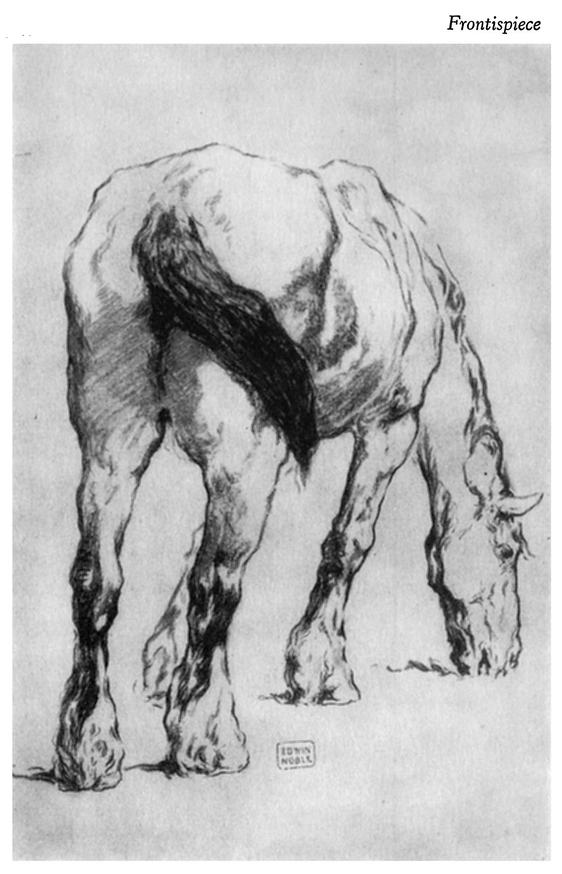

HORSE GRAZING

Bibliographical Note

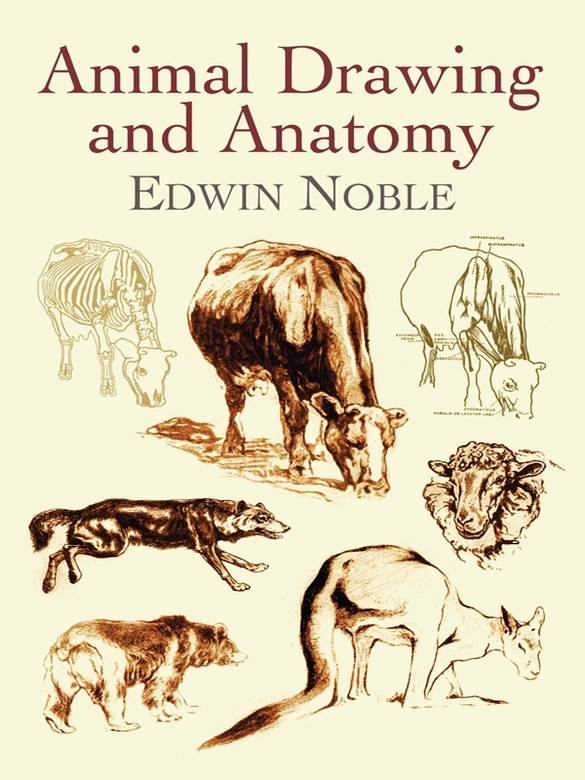

This Dover edition, first published in 2002, is an unabridged, unaltered republication of the text and illustrations from the work originally published in 1928 by B. T. Batsford, Ltd., London.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Noble, Edwin, 1876-1941.

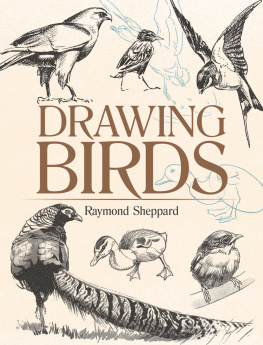

Animal drawing and anatomy / Edwin Noble.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : Batsford, 1928.

Includes index.

9780486148014

1. Animals in art. 2. Anatomy, Artistic. 3. DrawingTechnique. I. Title.

NC780 .N6 2002

743.6dc21

2002067288

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

PREFACE

N O artist, designer, or craftsman can be regarded as fully equipped without a knowledge of natural forms. All forms of life offer rich material for design, whether realistic or conventional. Study from the life, of the human figure, the forms of all animals and birds, and of the inhabitants of the waters, and of plants, must precede mastery of the art of design.

For that reason this book should be welcome to all students of art. While it is usual to teach drawing from the human figure and the study of plant forms, the decorative material provided by the forms of animals and birds has been almost entirely neglected. This book, therefore, is most opportune, coming as it does at a time when a little more interest is being shown.

After all, the study of animal and bird forms is right in the main stream of artistic tradition. The early sculptors made great use of this material, although rather naively at times. We find animals and birds often represented in the decoration of many of the buildings of the past, in mediaeval churches, and in heraldry, tapestry, and all forms of painting and decoration.

Nature is the mistress of decoration, and all who would understand it must sit at her feet. To the essential study of the clearly-defined law of pattern in Nature this book makes an important contribution.

Frank Brangwyn.

October 1928.

INTRODUCTION

A QUICK eye and unlimited patience are the great essentials for successful delineation of living birds and animals. When speaking of patience, I do not mean that which can only slavishly copy intricate details, but the patience which can afford to await opportunity. The figure painter may pose his models, but the animal painter can only snatch his opportunities. His model may remain still for half an hour, or half a minute; the latter is the amount of time most probable and all that he should allow himself, and in that short period he must make all his notes.

The drawing of animals whilst in the act of movement requires considerable skill and experience, and it is inadvisable to attempt this at too early a stage. The most satisfactory method is to wait for such momentary pauses as occur in attitudes of watching, listening or feeding, and, above all, every advantage taken of sleeping and sitting positions. These often show some exceptional foreshortening, and the knowledge so gained can be applied in future drawings wherein action is depicted. Whatever the position may be, however, every opportunity should be taken of the involuntary movements denoting the presence of life. It may be only the twitching of the tail tip, or angle of ears, but by their introduction is avoided all appearance of a dead or stuffed animal.

The simplest and most direct method of drawing should be cultivated from the commencement, the uncertainty of how long the model will retain the pose being sufficient to demonstrate the importance of this fact. A treatment so often advocated in other branches of art, namely, that of getting a general effect first, and adding details afterwards, is usually fatal to the student of animal drawing. In the event of change of position the sketch, however slight, should be complete in itself, with correctly suggested details of eyes, ears, or feet. Should the opportunity present itself of continued work upon the drawing, one can proceed with further elaboration.

Owing to the danger of getting two or more positions into one outline, it is inadvisable to attempt big alterations, but rather to commence a fresh drawing entirely.

A certain knowledge of the anatomy and characteristics of the various animals is also essential from the commencement. Hair requires to be treated as something of more importance to the visible form than can be suggested by a few haphazard scratches reminiscent of grass or cotton-wool, and the detail of the overlapping of feathers should be studied from the dead or stuffed model before proceeding far with sketches from life. Models for this purpose can often be purchased from the local poulterer; Pigeons, Pheasants, Guinea Fowl, Wild Duck, Hares, etc., making excellent material, and by the aid of skewers, pins, and cotton may be arranged in life-like positions of walking or flying.

Cultivation of the memory is a most important attribute, the mental visualization of a phase of action being indispensable, and, finally, every opportunity should be taken to make quick colour notes of the effect of light and sunshine upon plumage or the sheen of the coat.

Edwin Noble, F.Z.S.

October, 1928.

Table of Contents

HOODED MERGANSER DUCK

CHAPTER I

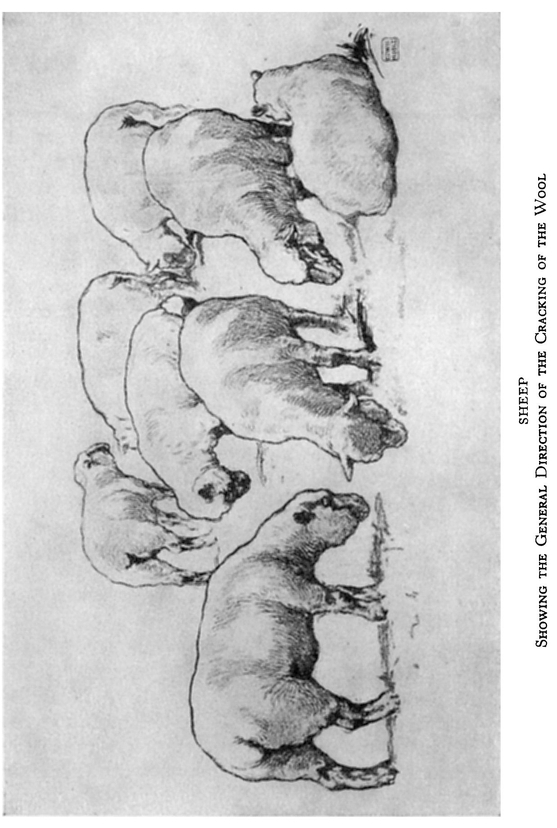

SHEEP

A S a model, the domestic sheep has always been of interest to the artist. Its stereotyped movements, constantly repeated by dozens of companions in its immediate vicinity, should logically mean an easy animal to study, whereas the contrary is the case and capable draughtsmen and painters when making such sketches find them most baffling, owing to the lack of any salient points to seize upon. This, however, is largely due to their own lack of knowledge of the one great important fact namely, the Anatomy of the Wool.

A general impression exists that feathers and hair grow from the body in a manner similar to that of the bristles from a door-mat. If that were so, we should expect to find a wrinkling of the feathers similar to that of the human skin becoming apparent at every point of movement during violent action. This, however, does not occur owing to the feathers themselves passing one above another by a telescopic or fanlike movement, laying closely overlapped upon the inner side and upon the outer side allowing a larger portion of each feather to be visible. On this account undue exposure of flesh is seldom noticeable in birds, but in the case of animals it is often more apparent.

Very few animals are without a coat or hairy covering in some form or another, and in most cases this has two characteristicsnamely, a woolly undergrowth close to the skin for the purpose of warmth, and an outer covering or thatch, of long and usually straight hairs, for protection against weather.