About the Author

Carolyne Larrington is Professor of Medieval European Literature, University of Oxford, and Official Fellow and Tutor, St Johns College. Her recent books include Winter is Coming: The Medieval World of Game of Thrones (2015), The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology (with Paul Acker) and a revised and expanded translation of The Poetic Edda (2014). She wrote The Land of the Green Man: A Journey through the Supernatural Landscapes of the British Isles (2015) and presented BBC Radio 4s accompanying series The Lore of the Land, exploring British folklore.

For JJ, JQ, LA and HOD

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Celtic Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends

The Egyptian Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends

The Greek and Roman Myths: A Guide to the Classical Stories

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

Old Norse names are cited in their Old Norse forms. This requires two unfamiliar letters (still used in modern Icelandic and Faroese), called eth ( / ) and thorn ( / ). The first of these is pronounced as the th sound in the, for example in the name of the king of the gods, inn (Odin). The second is pronounced as the th sound in thorn, as in the name of rr (Thor).

Scholars usually pronounce Old Norse words as if they were modern Icelandic. Stress falls on the first syllable. Most consonants are pronounced as in English (with g always hard as in gate, but j pronounced as y as in yes). So: Gerr = GAIR-ther (the capitals show the stress).

Vowels are also pronounced as in English when short, though short a is like a of father, not as in cat. y is the same as i: Gylfi = GIL-vee. ll is pronounced like tl: Valhll = VAL-hertl.

Long vowels (marked with an acute accent) are mostly just a longer version of the short ones, though is like ow as in how. The goddesses are collectively called the synjur = OW-sin-yur.

Diphthongs are somewhat different: ei or ey is ay, as in hay, so Freyr = FRAY-er; au is a little like oh, but longer than in English. draumar (dreams) = DROH-mar.

is pronounced eye, so the sir (the main group of gods) = EYE-seer.

and are like German : something like er. Thus Jtunheimar (the lands of the giants) = YER-tun-HAY-mar.

I would like to thank Tim Bourns for many useful suggestions and for his work on the index. The four dedicatees have been instigators of, and companions on, many Norse adventures in many lands: til gs vnar liggja gagnvegir, tt hann s firr farinn.

inn [Odin] was a man remarkable for his wisdom and in all accomplishments. His wife was called Frigida, and we call her Frigg. inn had prophetic abilities and so did his wife, and from this knowledge he discovered that he would become extremely famous in the northern part of the world, and honoured above all kings. For this reason he was eager to journey away from Turkey, and he brought a great multitude of people with him, young and old, men and women, and they brought many precious things with them. But wherever they went in the continent, so many splendid things were said of them that they seemed more like gods than men.

SNORRI STURLUSON, PROLOGUE, Prose Edda (c. 1230)

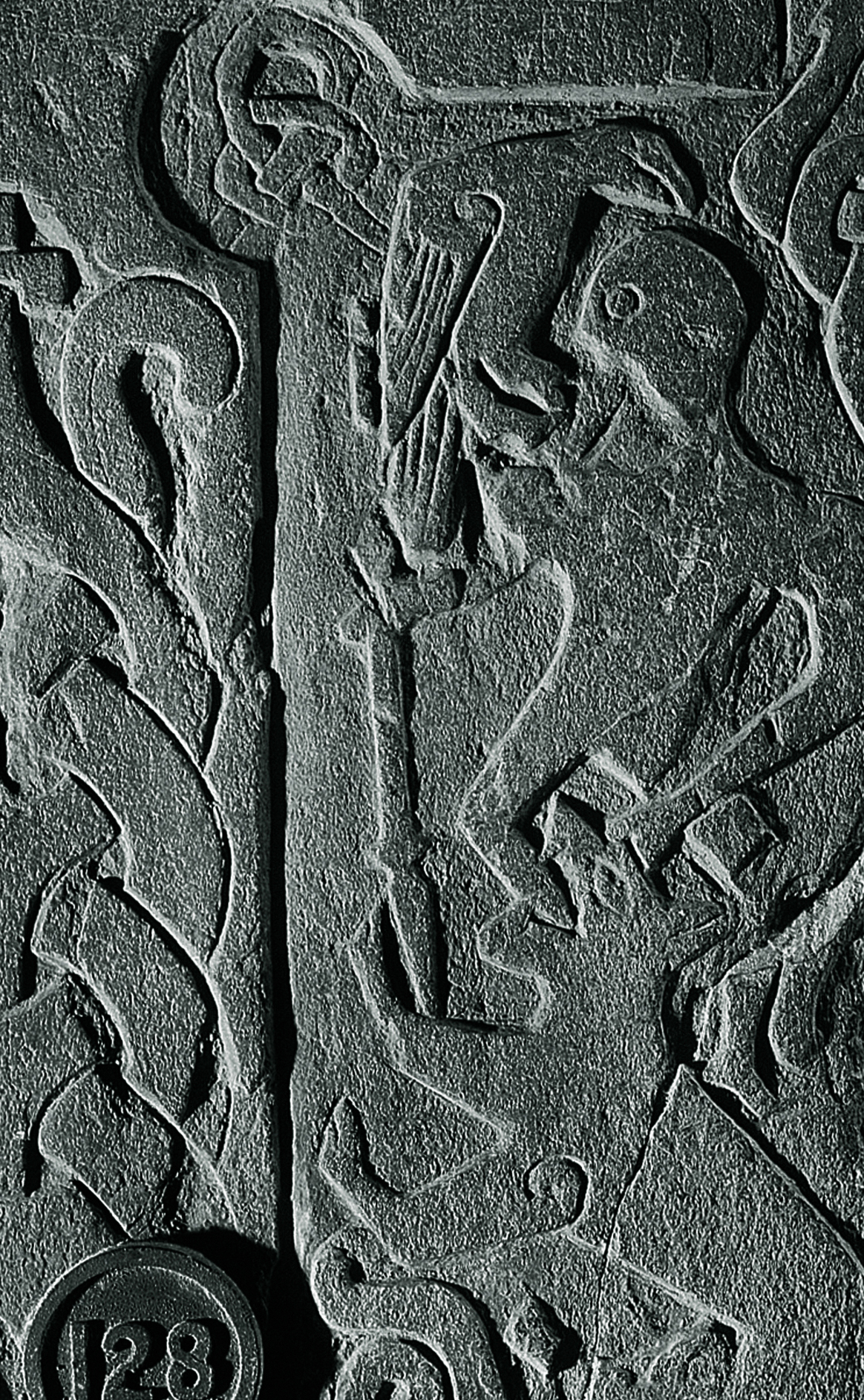

SNORRI STURLUSON AND THE CLEVER ASIAN MIGRANTS

Who were the Norse gods? Migrants from the Near East, journeying up through Germany to reach the promised Scandinavian homeland: humans like you and me, but smarter, handsomer, more civilized. Or so claimed one Christian writer, a medieval Icelander who recorded many of the myths and legends that have survived from the Scandinavian north. Medieval Christian scholars needed to explain why their ancestors worshipped false gods, and thus one widespread theory was that the pre-Christian gods were demons, wicked spirits sent by Satan to tempt humans into sin and error. But another very effective theory was the one put forward by Snorri Sturluson in the quotation above: the so-called gods were in fact exceptional humans, immigrants from Troy, an idea known as euhemerism. For Snorri Sturluson, the thirteenth-century Icelandic scholar, politician, poet and chieftain who left us the most complete and systematic account of the Norse pantheon, the idea that the Norse gods the sir as they were called must have been human beings was compelling. Descendants of the losing side in the Trojan War, they decided to migrate northwards, bringing their superior technology and wisdom to the natives of Germany and Scandinavia. The incomers culture overwhelmed that of the earlier inhabitants, who adopted the language of the new arrivals, and, after the death of the first immigrant generation, began to worship them as gods.

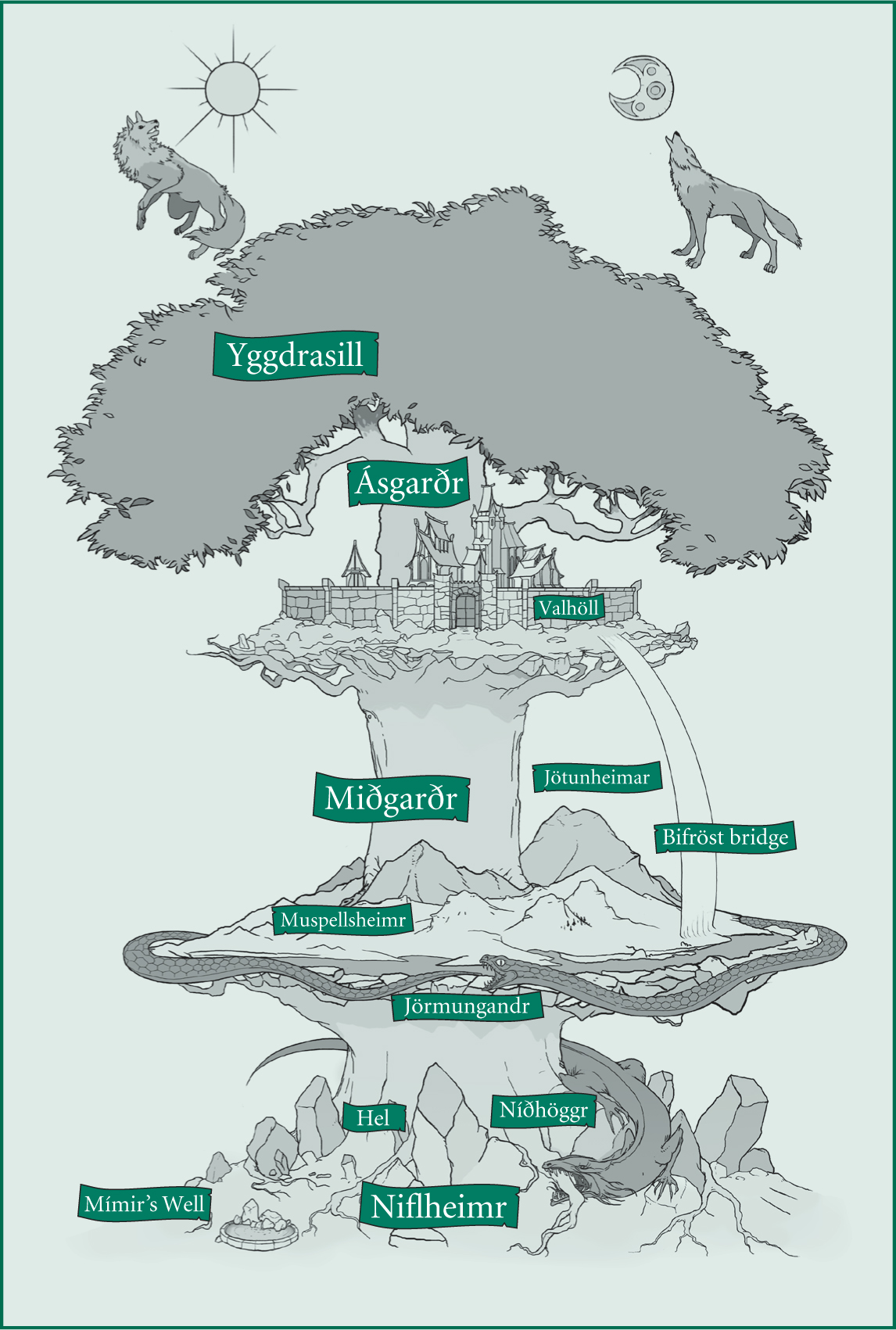

Snorris explanation of how traditional Norse poetry worked in his Edda required a good deal of mythological background information, and so he created a framework that made clear that while no one now might worship the pagan gods who were, anyway, nothing but a cunning tribe of Near Eastern migrants the stories associated with them were both meaningful and entertaining. He therefore prefaced his treatise on poetics with a tale about King Gylfi of Sweden who was doubly beguiled; first by the goddess Gefjun, as related in , and a second time when Gylfi realized too late that hed been tricked and set out for sgarr, where he knew the sir lived. Gylfi intended to find out more about these deceivers; he was admitted to the kings hall and there he met three figures called Hr, Jafnhr and rii (High, Just-as-High and Third). In a long question-and-answer session, Gylfi discovered a great deal about the gods, about the processes of the creation of the universe and of humanity, about the end of the world, ragnark, in which the gods and giants would battle one another, and finally how the earth would be made anew. And, advising Gylfi to make good use of what he had heard, Hr and his two colleagues, the mighty hall and the imposing fortress, all vanished. Gylfi returned home to relay to others what hed learned.

The Icelandic Scholar, Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson (11791241) belonged to a prominent Icelandic family and was deeply involved in the turbulent politics of Iceland and of Norway. He composed a treatise on poetics, known as the Prose Edda, which consists of four parts: a long poem illustrating various kinds of poetic metres called Httatal (List of Metres); Skldskaparml (The Language of Poetry), an explanation of the metaphorical figures known as kennings (see ); a

Next page