EARLY ROCK ART

OF THE AMERICAN WEST

EARLY ROCK ART

OF THE AMERICAN WEST

THE GEOMETRIC ENIGMA

EKKEHART MALOTKI

ELLEN DISSANAYAKE

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle

Early Rock Art of the American West was made possible in part by generous gifts from Nancy Aiken, Dorothe and Horst Antes, Peter Blystone, Nina Bowen, Betsy and John Darrah, Harold Fromm, the Bertram S. and Ruth M. Grand Charitable Gift Foundation, Carter Hagerman, Joseph and Karen Hendrickson, Jim I. Mead, Keith and Pieter Schaafsma, Roger Seamon, Christina Singleton, Charles and Susan Routh, Pat Soden, and Marilyn Trueblood.

Copyright 2018 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in South Korea

Design by Laura Shaw Design

Composed in NCT Granite, typeface designed by Nathan Zimet; and Intro Rust, typeface designed by Ani Petrova, Svet Simov, and Radomir Tinkov

222120191854321

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Photographs are by Ekkehart Malotki unless otherwise noted.

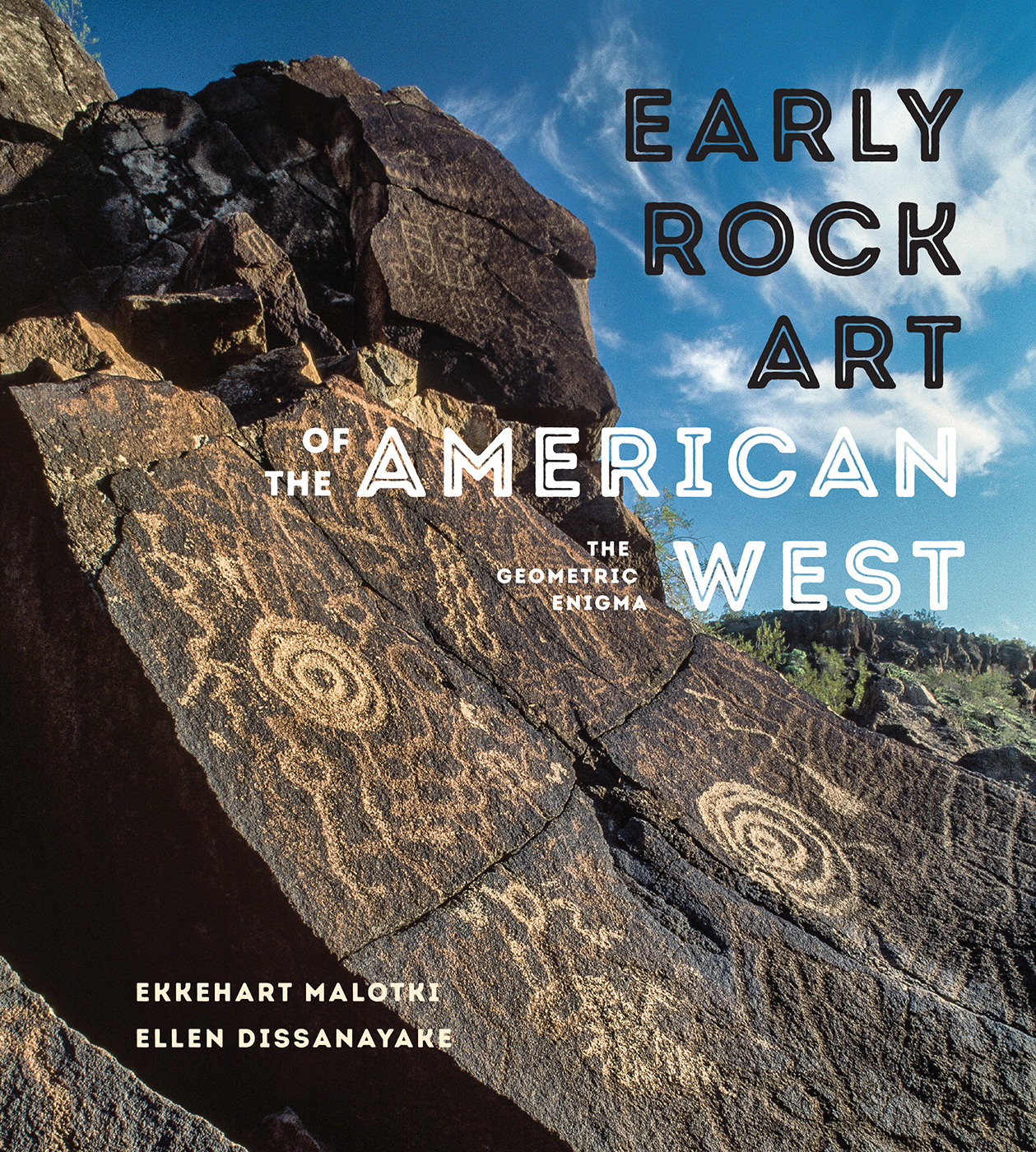

Frontispiece: Classic Carved Abstract Style petroglyphs from Arizona, exemplifying the earliest rock markings of the American West

University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Malotki, Ekkehart, author. | Dissanayake, Ellen, author.

Title: Early rock art of the American west : the geometric enigma / Ekkehart Malotki and Ellen Dissanayake.

Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017050791 (print) | LCCN 2017051145 (ebook) | ISBN 9780295743622 (ebook) | ISBN 9780295743608 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780295743615 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Indians of North AmericaWest (U.S.)Antiquities. | PetroglyphsWest (U.S.). | Picture-writingWest (U.S.) | Rock paintingsWest (U.S.) | West (U.S.)Antiquities.

Classification: LCC E78.W5 (ebook) | LCC E78.W5 M27 2018 (print) | DDC 709.01/130978dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017050791

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

TO ALL THE PALEOAMERICANS, WHOSE PRICELESS LEGACY OF ROCK ART

OFFERS US AN EVER-PRESENT SOURCE OF MYSTERY AND MARVEL

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EKKEHART MALOTKI

Reflecting on how this book came to be, I see the fortuitous conjunction of several factors and events. Communing photographically with rock art sites and trying to capture the essence of petroglyphs and pictographs in their surroundings has been a passion of mine for many years. After completing my comprehensive overview of Arizonas wealth of rock art in 2007, I felt the need for a new undertaking that would allow me to roam the desert-, mountain-, and canyon-scapes of the American West in search of rupestrian paleoart.

Two years earlier I had experienced an unforgettable high in my rock art life when, in the company of French prehistorian Jean Clottes, I had the great privilege of standing in front of the fabulous Ice Age bestiary of Grotte Chauvet-Pont dArc. Marveling at the breathtaking images, I was struck by the fact that such naturalistic depictions, with a few exceptions, appeared to be completely absent at any of the earliest rock art sites in the American West. Surely we can assume that the first Paleoamericans arrived on a continent teeming with Pleistocene megafauna. If so, why had they refrained from painting or engraving images of these animals, some of which they depended on for food, and others that were dangerous and had to be feared? Why did they choose instead, almost exclusively, to make purely abstract-geometric motifs? These questions seemed worth probing.

Furthermore, what accounted for the uniformity of all those archetypal geometric designs? Similar motifs have been found on every continent, with the exception of Antarctica. Was it thinkable that all of them were created by trancing shamans, as advocated by David Lewis-Williams? Disenchantment with this explanatory hypothesis had already taken root in me while considering and discussing Arizonas geometric paleoart. In addition, I now also had the opportunity to observe my grandson, Emil, as his drawing behavior developed like that of all young children. He certainly was not a little shaman, experiencing an altered state of consciousness as he created his dots, lines, and circle elements. What inspired him to do so?

I meanwhile had also been exposed to two eye-opening publications, What Is Art For? and Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes From and Why, by Ellen Dissanayake. Ellen is hard to label. An interdisciplinary scholar, she bases her ideas on knowledge derived from the fields of ethology, evolution, cultural anthropology, neuroscience, developmental psychology, theory and practice of the various arts, and now, for this book, paleoarchaeology and cognitive archaeology. Her insight that art is an innate behavior that had been critical in the evolutionary process of human survival, sparked in me a flash of comprehension tantamount to an epiphany. Ellen first defined artful behavior as making special and later coined the term artifying as a more academically acceptable synonym. This concept offered a useful, all-encompassing framework for considering the multitude of iconographic expressions of the rock art I knew. Among the tens of thousands of impressive paintings and engravings that populate the western landscape, there are a million more that do not meet the modern art criteria of beauty and outstanding aesthetic appeal, but which nevertheless demonstrate artful behavior, or artifying. Here was an epistemological approach that would be useful in dealing with the abstract paleoart of the American Westan approach that regarded rock art not as something to be viewed like paintings in an art gallery but understood as the residue of ceremony and ritual in which performance (doing and making) mattered more than the resulting graven or painted image.

Encouraged by the fact that Ellen had agreed to read my manuscript on Arizonas rock art and then actually wrote a blurb for the book, I offered to introduce her, who had visited some of the well-known French caves including Lascaux, to the world of open-air rock art by taking her to some of my favorite petroglyph and pictograph sites in northern Arizona. The rest is history, and the results are reflected in the individual chapters of this book. The decision to collaborate on the book would provide Ellen, as one concerned with the arts of all kinds in all times and places, with the opportunity to delve into a new field, rock art. For me it would be an opportunity to indulge in my favorite pastime: the pursuit of rock art research and photography. Clearly, during the past three decades, some of the happiest hours of my life were spent engaging photographically with a newly discovered rock art painting or engraving. Such close encounters with rupestrian images were further enhanced when I was joined by friends who shared my enthusiasm. One of my most memorable occasions of this kind occurred when I was able to introduce my son Patrick, his wife, Julia, and my two grandchildren, Emil and Annelie, to Utahs Upper Sand Island panel with the two exceptional mammoth depictions.