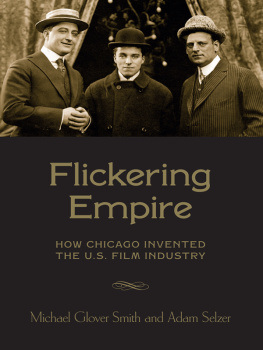

Flickering Empire

Flickering Empire

HOW CHICAGO INVENTED THE U.S. FILM INDUSTRY

Michael Glover Smith and Adam Selzer

A Wallflower Press Book

Published by

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright Michael Glover Smith and Adam Selzer 2015

All rights reserved.

E-ISBN 978-0-231-85079-7

Wallflower Press is a registered trademark of Columbia University Press

Cover image:

Charlie Chaplin with Francis X. Bushman and Broncho Billy Anderson.

Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

A complete CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-231-17448-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-17449-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-85079-7 (e-book)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

For Jillian and Ronni

Table of Contents

by Susan Doll

T he authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals and institutions for their generous help during the writing of Flickering Empire: Yoram Allon and everyone at Wallflower Press; Lisa Wagner for her invaluable advice, editorial work and tireless championing of this book from the beginning; George Walsh for his proofreading, editing and good taste in French bakeries; Jeff Look, the great-nephew of Colonel William Selig, for having us over for dinner and allowing us access to the family archives; Diana Dretske and the Lake County Discovery Museum in Wauconda, IL; the Chicago History Museum; the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.; Gary Keller, Vice President, Essanay Centers and Strategic Initiatives at St. Augustine College; and the residents of 3900 N. Claremont Avenue.

Michael Glover Smith wishes to acknowledge: my wife Jill whose love and support made this project possible; Adam for showing me the ropes in researching and writing non-fiction; my father David; my mother Corrine (who accompanied me to the Chicago History Museum in 2010 a trip that proved to be an important part of the genesis of this book); my brother Drew (who read an early draft of the manuscript and offered helpful feedback); Susan Doll and Sara Vaux for their friendship and mentorship in the field of Film Studies; and all of my colleagues and students at Oakton Community College, Harold Washington College, the College of Lake County and Triton College.

Adam Selzer wishes to acknowledge: the kind staff at the George Eastman House in Rochester who arranged for screenings of a handful of early films that could be seen nowhere else, and the organizers of the Teen Book Fest in Rochester who sponsored my trip there. To Ronni for putting up with my endless rambling, to Aidan for sitting through my experiments to see whether nine-year-olds still find century-old slapstick funny (results: affirmative!), and to Mike, whose hard work and dedication made the project possible. Thanks also to Hector Reyes, my partner in podcasting, for accompanying us on our expeditions to the remains of the old studios.

by Susan Doll, PhD

I lived in Chicago for 25 years, and, in that time, I discovered it to be a city of contradictions. It is a city that earned fame for the contributions of progressive thinkers in social sciences, education, and religion, but ignominy for its legacy of political corruption. A beacon for clever entrepreneurs such as Cyrus McCormick and Aaron Montgomery Ward, Chicago also attracted con men like Joseph Yellow Kid Weil. Righteous Billy Sunday, who preached about the evils of alcohol during Prohibition, is buried in a Chicago suburb called Forest Park, five miles due east from the Hillside grave of ruthless Al Capone, who became rich and infamous for selling illegal liquor during the same period of time. A city on the make, to quote writer Nelson Algren, Chicago was the perfect place for the burgeoning film industry to develop and prosper.

Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry offers the full story of Chicagos enormous contributions to the history of cinema. Like Chicago, the film industry was a modern wonder that attracted as many notorious characters as it did innovative entrepreneurs. And, sometimes those contradictory impulses were represented in the same person! Readers will learn about Colonel William Selig, who not only was a phony medium in Dallas when he saw his first motion picture but also was a phony colonel. Selig returned to Chicago to jump into the business of manufacturing motion-picture equipment, in which enterprise he became a key figure. The 1893 Worlds Columbian Exposition is a celebrated event in Chicagos history and also a notorious one, because of the escapades of serial killer H.H. Holmes, though Flickering Empire focuses on the fairs influence on the beginning of the film industry. It was at the fair where George Spoor, Seligs rival for many years, saw the Tachyscope, a rotating wheel with photographs mounted around the periphery. When spun, the images were animated, suggesting the illusion of movement, which intrigued Spoor.

The failures and successes of Chicagos film pioneers are not the only scandalous events in early cinema history recalled in Flickering Empire. Readers will discover the truth behind Thomas Edisons role in the invention of the motion-picture camera and the establishment of the cinema industry. Authors Michael Glover Smith and Adam Selzer provide details of Edisons penchant for taking credit for the innovations of his assistants, including the work of W.K.L. Dickson, the man who made the inventors ideas for a camera that captured movement actually work. They expose Edisons ruthless tactics in suing rivals for control of film production and distribution, his bootlegging of European films, and even his lack of interest in improving the production values of his films. Edisons tactics stunted the development of the industry on the East Coast, which helped studios and distributors in Chicago to expand and dominate production and distribution for a short while.

The authors effectively paint the big picture of the pioneering days of cinema history and then carefully place Chicagos major contributions within it. But the devil is in the details, and their incredible research in primary sources pinpoints dates, people, and films to carefully support their argument about the central role of Chicago-based film entrepreneurs and the superior production values of their movies. Indeed, the detailed descriptions of films in the chapters on the Essanay and Selig Polyscope Studios are among the most fascinating segments in a book written in a direct, entertaining style. In 1907, cross-eyed comic Ben Turpin, later a part of Mack Sennetts Keystone Studios, skated his way into a movie career in Essanays first official movie,