About the Author

Bruno David is Associate Professor in archaeology at the Monash Indigenous Centre, Monash University, Australia. His books include Hiri (with Robert Skelly, 2017), the World Archaeological Congress Handbook of Landscape Archaeology (co-edited with Julian Thomas, 2008), The Social Archaeology of Australian Indigenous Societies (co-edited with Bryce Barker and Ian McNiven, 2006), Landscapes, Rock-Art and the Dreaming (2002), and Inscribed Landscapes (co-edited with Meredith Wilson, 2002). In 1994 he was awarded the inaugural Antiquity Prize for his work on the archaeology of meaning in rock art, in 2007 the Australian Archaeological Association's Bruce Veitch Award for Excellence in Indigenous Engagement, and in 2013 the Ben Cullen Prize for writings on the social construction of caves and rockshelters. His current research involves working in partnership with Indigenous communities in northern Australia and Papua New Guinea, exploring the historical connections that people have formed with places and documenting the antiquity of rock art and its meaning to local communities today.

This famous series provides the widest available range of illustrated books on art in all its aspects.

To find out about all our publications, including other titles in the World of Art series, please visit www.thamesandhudson.com. There you can subscribe to our e-newsletter, browse or download our current catalogue, and buy any titles that are in print.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art

Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods

The Complete World of Human Evolution

The Complete Ice Age: How Climate Change Shaped the World

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

. Head of a rhinoceros from The Three Rhinoceroses Frieze in the cave of Rouffignac, France. The art remains undated, but through stylistic associations with other, dated Ice Age sites of Western Europe is thought by some researchers to be about 15,000 years old.

For my dear little boy Jasper, who brings joy all day long

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 as Cave Art

ISBN 978-0-500-20435-1

by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

and in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

Cave Art 2017 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

This electronic version first published in 2017 by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

This electronic version first published in 2017 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

eISBN 978-0-500-77381-9

eISBN for USA only 978-0-500-77382-6

To find out about all our publications, please visit

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

: 15,500-year-old cave painting of a bison in the Salon Noir, Niaux Cave, French Pyrenees.

Photo: Pascal Goetgheluck / Science Photo Library

Contents

In theory, artists can depict anything they wish, but they dont. Claire Smith, former President of the World Archaeological Congress

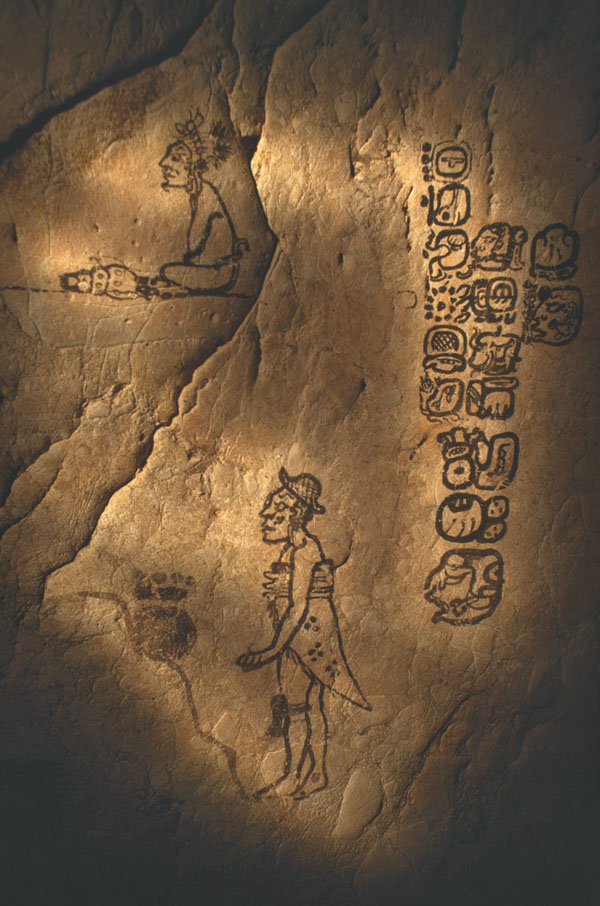

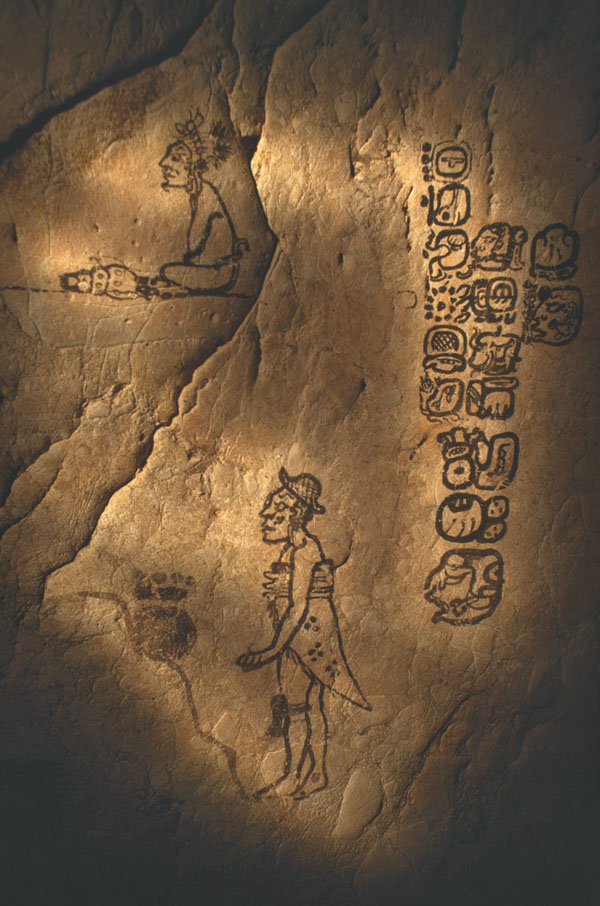

In 1979 a remarkable discovery deep in the jungles of Guatemala revealed to the world a hitherto unknown underground realm of Maya art. The cave of Naj Tunich [] gave testimony to a sacred landscape that had remained preserved for centuries. Maya ethnography and ancient writings enabled the art and rituals to be deciphered, a knowledge to which we will return in the final chapter of this book.

. Entrance to the cave of Naj Tunich, Guatemala, where a previously unknown subterranean world of Maya art and religious performance was rediscovered in 1979.

).

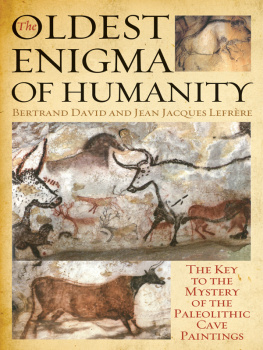

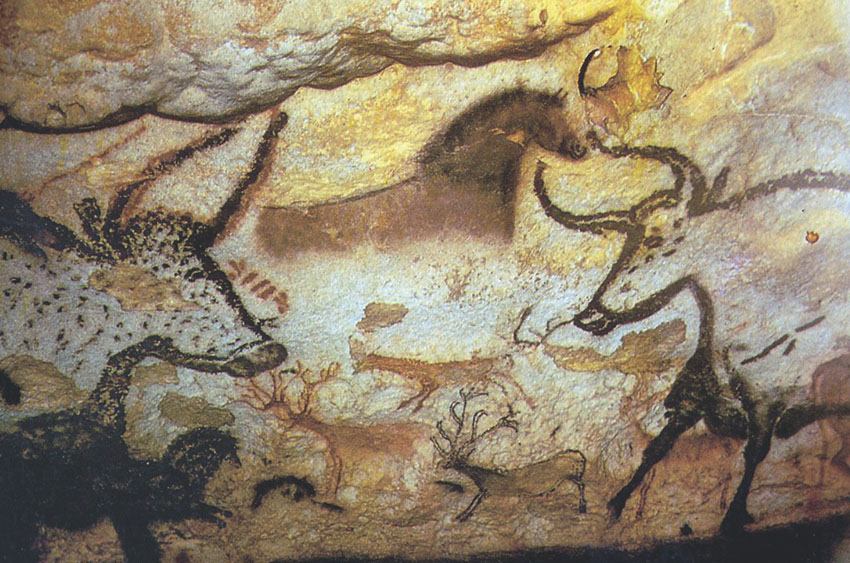

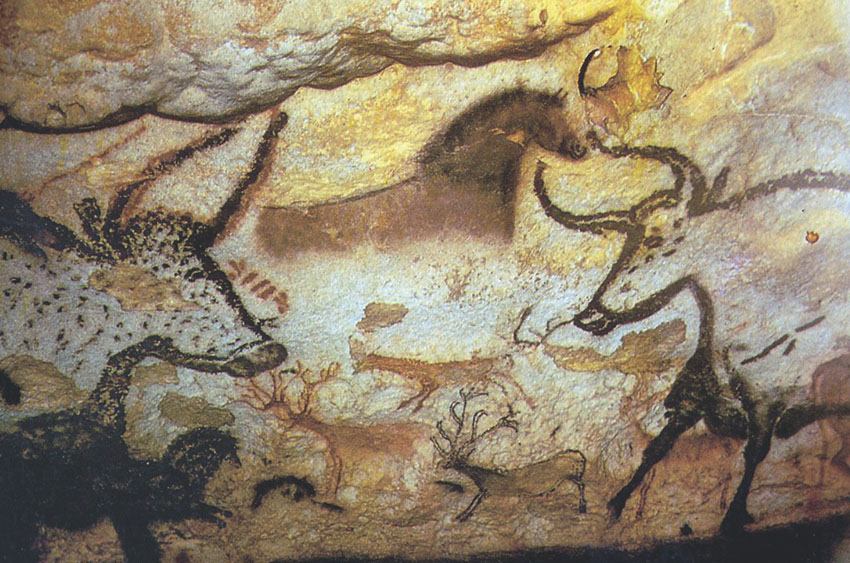

In that same year, on the other side of the Atlantic, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) added a number of well-known French Ice Age caves richly decorated with rock art dating back some 12,000 years and more to its World Heritage List. Among these was the crowning jewel of the French Upper Palaeolithic, the cave of Lascaux with its ochre red, yellow and black pantheon of painted bulls, horses ]. But unlike Naj Tunich, those French sites had no ethnography of any kind, no way of making sense of what the art meant to people so many thousands of years ago.

. Upper Palaeolithic paintings dating to the Ice Age in the Hall of Bulls, Lascaux, France.

After decades of enquiry, sometimes with considerable insights, we continue to ask: who made these fantastic paintings, deeply buried in the hollows of the earth, and why? The artists of Naj Tunich and Lascaux belonged to very different worlds and very different times, and they came from cultures utterly unlike our own. Understanding their artwork thus necessitates understanding not just the artists as individuals who painted, but also the cultures from which they came. While to some degree the works of art can be seen as the creations of individual artists, they cannot be reduced to the genius of entirely free minds, of blank slates, because how people choose to do things is to some degree conditioned by their cultural traditions. Furthermore, while an artist can decide to make or do something, the end product is rarely exactly what was anticipated at the start of the work. What we see in the art that adorns the cave walls of Naj Tunich and Lascaux, as with cave art all over the world, is as much the product of subliminal cultural forces that shaped how people once saw the world as it is the intentions of individual artists. And what we see in those caves also reflects how we ourselves, as observers, have been conditioned to see.

Many theories have been developed over the past 150 years to explain cave art. These have tended to be Grand Theories that tried to make sense of the art by reference to a single, overarching logic. Back in the nineteenth century, when cave art first began to be rediscovered in Spain and France, it was generally thought that the art was made for its own sake art for arts sake as presumably ancient humans were too primitive for higher kinds of reason. Then notions of totemism and hunting magic became prevalent, as the world views and religious practices of living Indigenous peoples came to be documented, those new inspirations being applied to the art of Ice Age Europe. But as Indigenous communities continue to remind us today, their cultures, their artistic practices, relate to their own ways of doing things, to their own, very particular histories, not to that of others with whom they have never had any direct or even indirect contact in other parts of the world (see as the 1970s had done. Yet the new explanations again came to marginalize peoples, cultures and ways of being, and as much so as the earlier Grand Theories had done, for these new explanations were also Grand Theories that paid no real attention to the reasons why particular cultures had made art in the distant past, or, in the case of most Indigenous groups across the world, why they made art recently or continue to do so today. They did not give voice to the practices and motivations of the very people who had made the art, where this was known. This is often the fate of Grand Theories that do not address or neatly fit into the ways of all.