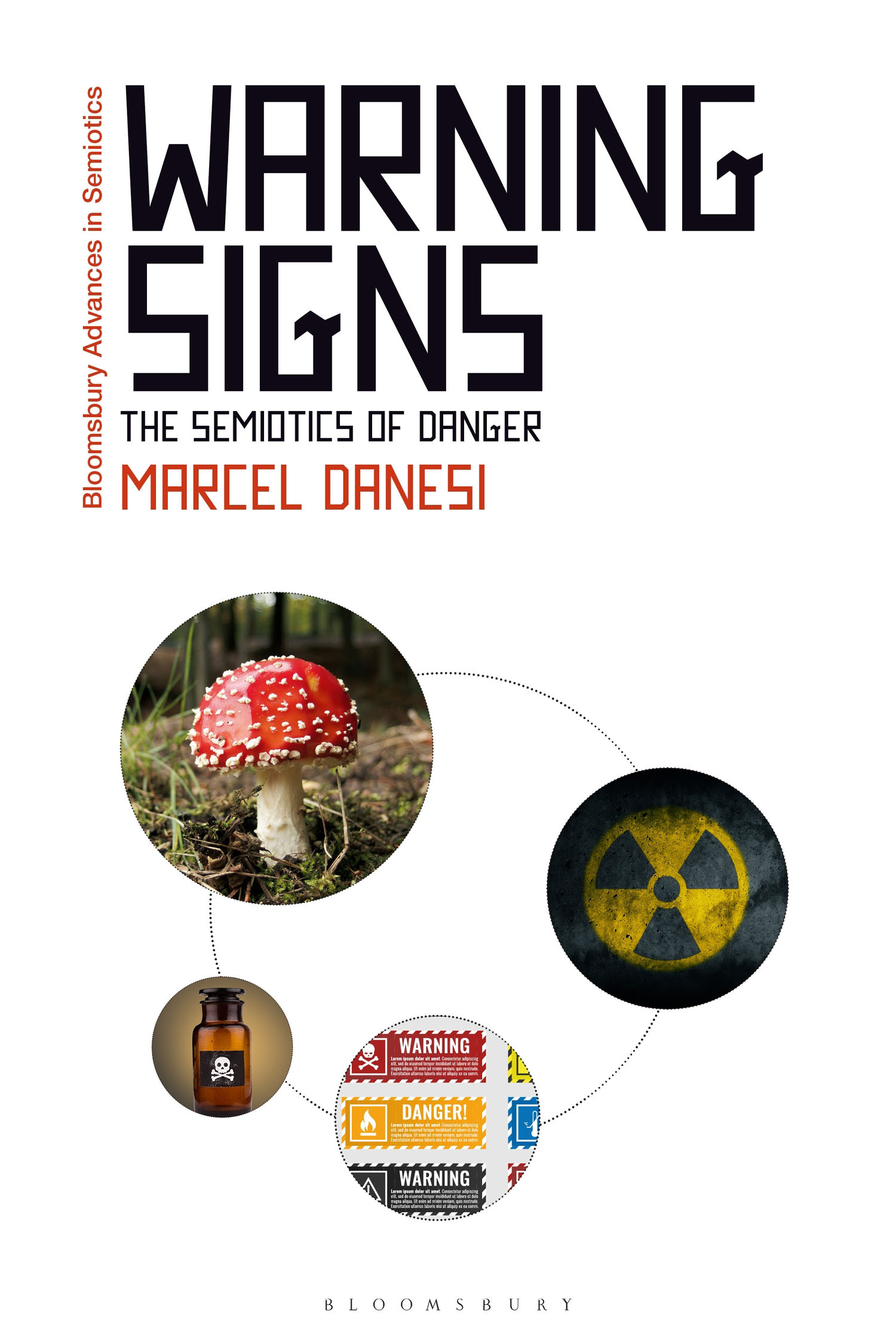

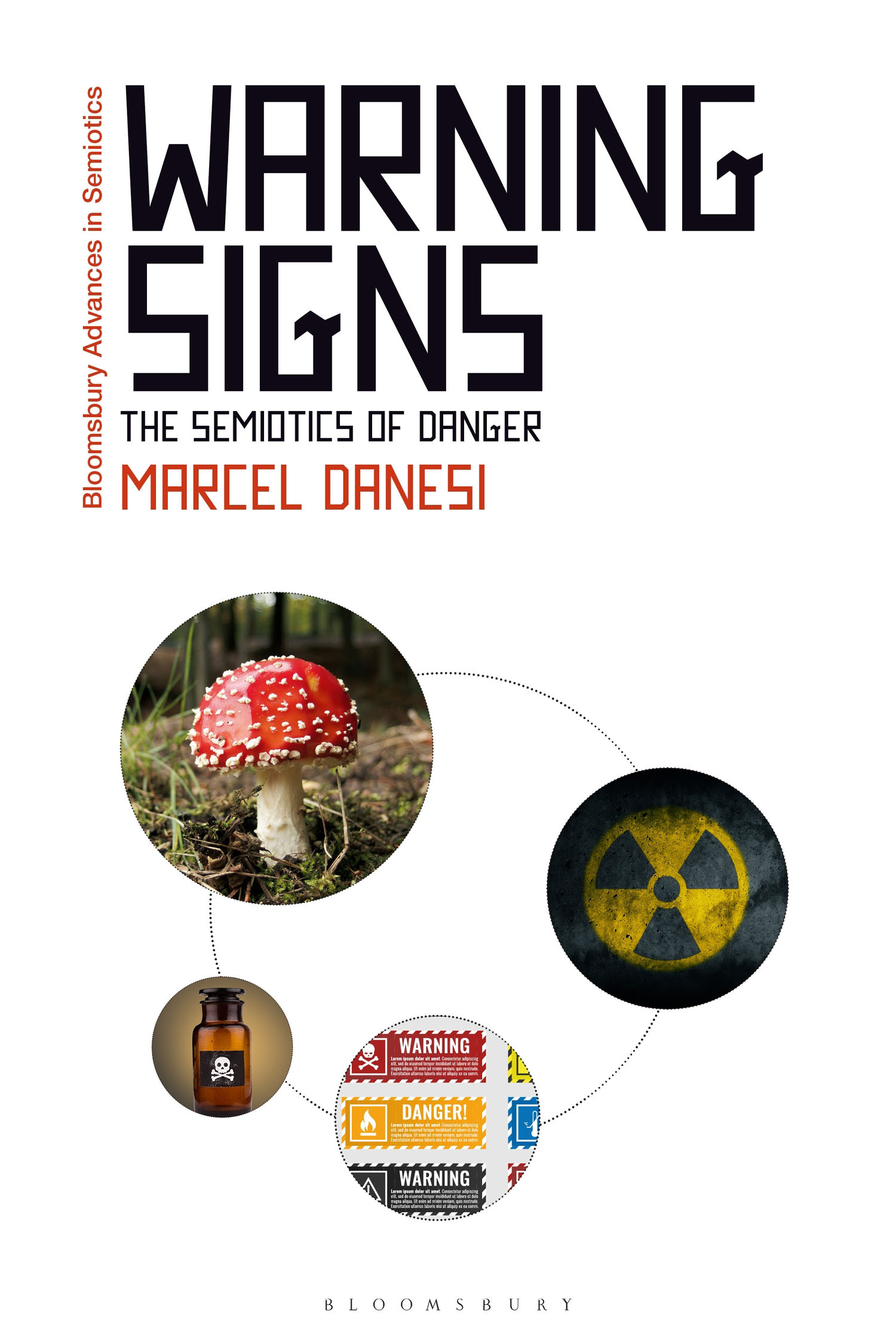

Warning Signs

BLOOMSBURY ADVANCES IN SEMIOTICS

Semiotics has complemented linguistics by expanding its scope beyond the phoneme and the sentence to include texts and discourse, and their rhetorical, performative, and ideological functions. It has brought into focus the multimodality of human communication. Bloomsbury Advances in Semiotics publishes original works in the field demonstrating robust scholarship, intellectual creativity, and clarity of exposition. These works apply semiotic approaches to linguistics and non-verbal productions, social institutions and discourses, embodied cognition and communication, and the new virtual realities that have been ushered in by the Internet. It also is inclusive of publications in relevant domains such as socio-semiotics, evolutionary semiotics, game theory, cultural and literary studies, humancomputer interactions, and the challenging new dimensions of human networking afforded by social websites.

Series Editor: Paul Bouissac is Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto (Victoria College), Canada. He is a world-renowned figure in semiotics and a pioneer of circus studies. He runs the SemiotiX Bulletin [www.semioticon.com/semiotix] which has a global readership.

Titles in the series include:

Cognitive Semiotics, Per Aage Brandt

Computational Semiotics, Jean-Guy Meunier

Music as Multimodal Discourse, edited by Lyndon C. S. Way and Simon McKerrell

Peirces Twenty-Eight Classes of Signs and the Philosophy of Representation, Tony Jappy

Semiotics of the Christian Imagination, Domenico Pietropaolo

The Languages of Humor, edited by Arie Sover

The Semiotics of Caesar Augustus, Elina Pyy

The Semiotics of Clowns and Clowning, Paul Bouissac

The Semiotics of Emoji, Marcel Danesi

The Semiotics of Light and Shadows, Piotr Sadowski

The Semiotics of X, Jamin Pelkey

The Social Semiotics of Tattoos, Chris William Martin

Contents

Explosion image.

Hazard pictogram.

Revised hazard pictogram.

GHS hazard pictogram.

Cave of Beasts, Gilf Kebir, Libyan Desert.

Vesuvius Erupting at Night, William Marlow.

Trefoil pictogram.

The Scream, Edvard Munch.

US Department of Energy danger symbol, 2004.

Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, Edvard Munch, 1919.

Girls on the Pier, Edvard Munch, 1904.

Radiation warning pictogram.

WIPPs warning text.

WIPPs information center.

Line drawing (Hudson 1960).

Tombstone warning, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Egypt.

Hunger stone, Dn, Czech Republic,

Part of the Rk runestone, deshg in stergtland, Sweden.

Japanese tsunami stone, Aneyoshi.

Hopi prophecy rock, Oraibi, Arizona

Hopi prophecy etching (Waters 1963).

Cueva de las Manos, Santa Cruz Province, Argentina.

Cave painting, Lascaux, France.

Cueva de la Pileta, Mlaga, Spain.

Aztec ritual for flooding, Diego Durn.

Noahs Ark, Gerona Beatus, 975 CE .

Apocalypse, Biblia Pauperum, c. 131517

Disastro naturale, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1517.

Alluvione, Michelangelo Buonarroti, c. 1508.

Esto es lo verdadero, Francisco Goya, 1820.

Skull and crossbones symbol.

Biohazard pictogram, Dow Chemical, 1966.

Neolithic triskelion.

Hypothetical semantic differential for climate change.

cave art, Sulawesi.

Covid watch pictogram.

Coronavirus emoji.

Coronavirus illustration, Centers for Disease Control.

Danse of Death, Michael Wolgemut, 1493.

Signs of danger are everywhere. Some are human-made ones designed as specific warnings, such as the typical labels indicating the presence of poison in bottles or the hazard placards alerting people to the presence of toxic waste at specific locales. Others are immanent in the environment, including extreme meteorological events such as hurricanes and tsunamis, which are natural warning signs of danger to human life. How do we understand warnings and the dangers they represent? What do they tell us about the sense of danger itself? How have humans perceived and dealt with danger across time and across cultures? Are paintings on prehistoric cave walls the first recorded images of danger and fear? Are ancient flood myths cautionary warning tales of human destructive activities?

These are the kinds of questions that fall directly under the analytical rubric of semioticsthe science of signs. But, as far as can be told, this discipline has been used only once in the past to study danger and warning sign systems explicitlynamely by the late American semiotician, Thomas A. Sebeok, who was commissioned by the US Department of Energy in 1981 to come up with a set of recommendations for designing effective warning signage to be placed at the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste depository site in Nevada that would withstand the test of time, remaining understandable to people 10,000 years into the future, given that the radioactive waste at the site would remain dangerous until then. Sebeoks recommendations were published in a report in 1984 (Communication Measures to Bridge Ten Millennia)a report that is still being discussed to this day, perhaps because of some of its seemingly quirky suggestions (as will be discussed in this book). Significantly, it was instrumental in laying the groundwork for a new branch or subfield of semiotics to emerge, nuclear semiotics, bolstered by the publication of a special 1984 issue of the German periodical, Zeitschrift fr Semiotik, dedicated to the study of the different ways in which warning signage could be made effective and enduring across long stretches of time in the future.

However, very little has been done in this subfield since then, with only a handful of studies having come forth that utilize semiotics in the context of the dangers that environmental crises pose to human survival (for example, Leone 2012 and Abbati 2019). It was not, actually, the initial goal of nuclear semiotics to extend its purview in this way. However, because Sebeok examined methods for making signs withstand meaning decay and how danger can be communicated effectively, a broader reach of nuclear semiotics was implicit from the outset. The objective of this book is, in fact, to extend the reach of nuclear semiotics, applying it to the general study of danger and warning signage, in the hope that it can provide relevant insights on current crises, such as climate change and the rise of infectious diseases, from the angle of how they are perceived and represented (in language, in images, in stories, and so on). This line of inquiry may, itself, suggest ways of devising meaningful social action to curb the destructive human activities that may have brought them about. As far as I know, nuclear semiotics has rarely been envisioned in this wayas a means to suggest a course of action that will hopefully be beneficial to enhancing human survival. While this might seem to be an extravagant claim, the argument will be made throughout this book that it is not.

The fear of extinction that people have always faced has been an unconscious archetypal theme in all representational modes, from the early cave-wall drawings and ancient flood myths to subsequent narratives and poetry. All these semiotic artifacts have withstood the test of time, in line with what Sebeok himself emphasized. The warnings placed on ancient Egyptian tombs, alerting visitors of the dire consequences they would face if they entered them, are as understandable today as they were when they were created. The tales of apocalyptic scenarios portrayed in the ancient myths, harboring warnings of impending doom and existential uncertainty, similarly resonate with us to this day. As Alaszewski (2015: 205) has aptly put it: All societies have [had] to cope with uncertainty, the essential unpredictability of the future and account for past misfortunes. In his fieldwork with the Trobriand Islanders, the Polish-born British anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski (1922) discovered the importance of rituals, stories, and sayings as part of an unconscious folkloric code for coping with uncertainty. Much can be learned from studying such codes from the past, since they persist in different forms to this day (Douglas 1966). Science is also a strategy for taming uncertainty, based on empirically-testable predictions rather than mythical ones. Epidemiologists, for example, correlate the incidence of a pandemic disease to its spatial, temporal, and social distribution, so as to provide a statistical basis for anticipating or preventing future incidences of the disease. Nevertheless, as will be discussed throughout this book, reliance on folkloric-mythical-symbolic codes as effective warning systems has not disappeared in an age of science, as Sebeok emphasized in his 1984 report.

Next page