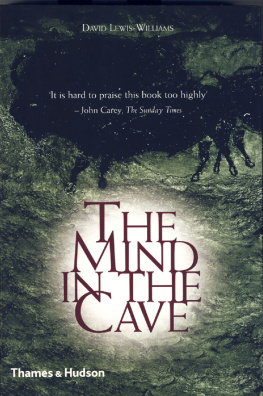

The Mind in the Cave

DAVID LEWIS-WILLIAMS

The Mind in the Cave

CONSCIOUSNESS AND THE ORIGINS OF ART

Copyright 2002 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

This ebook edition first published in 2011

First published in the United Kingdom in 2002 by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

www.thamesandhudson.com

First published in 2002 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN for USA and Canada: 978-0-500-77044-3

UK and the Rest of the World: 978-0-500-77030-6

Contents

Preface

Mankind always sets itself only such problems as it can solve; since, looking at the matter more closely, it will always be found that the task itself arises only when the material conditions for its solution already exist or are at least in the process of formation.

KARL MARX, A CONTRIBUTION TO THE CRITIQUE OF POLITICAL ECONOMY(1859)

The publication of this book marks the end of a century of research on Upper Palaeolithic art and the beginning of another. It was in 1902 that Emile Cartailhac, an influential French archaeologist who had vehemently contested the authenticity of the finds that had been made in the French and Spanish caves, recanted and published his now-famous article Mea culpa dun sceptique. The widespread, though not complete, scepticism that had denied the prehistoric people of the Upper Palaeolithic period the ability to produce art at once fell away. At a stroke, the study of Upper Palaeolithic art became respectable, and a new academic industry was born.

Now, just over a century later, we ask how much we have learned since Cartailhac changed his mind. Certainly, our knowledge of the facts of Upper Palaeolithic art has increased enormously. We know of far more sites, both underground and in the open air; we have detailed inventories of the images in most of the major sites; many caves have been surveyed, and we have maps showing the precise location of each and every image; we know the dates of many of the images; we have huge collections of beautifully made portable art; caves and rock shelters have been meticulously excavated; we even know the ingredients of some of the paints that the ancient images-makers used. Yet, despite all this information, we seem no closer to knowing why the people of that period penetrated the deep limestone caves of France and Spain to make images in total darkness in addition to those in daylight areas and on pieces of portable stone, bone, ivory and antler. We do not know what the images meant to those who made and those who viewed them. At least, there is no unanimity on these key points, and the greatest riddle of archaeology how we became human and in the process began to make art continues to tantalize.

Many researchers, especially those in France and Spain, believe that still more facts are required before we can theorize. But how will we know when we have enough data to begin work on explanation? Will our data reach a critical mass, implode and automatically reconfigure as an explanation? Hardly. Or is it not so much a matter of quantity of data as some crucial piece of information, some exceptionally perceptive observation still to be made in the caves, that will cause all the other accumulated data to fall into place and provide us with a persuasive explanation? We may as well search for the Holy Grail.

Although Karl Marx may be overly optimistic in the epigraph to this Preface, I believe that a century of research has indeed provided us with enough data, the material conditions, to hazard a persuasive, general explanation for a great deal of not all Upper Palaeolithic art, and, moreover, to explain some hitherto inexplicable features of the imagery and its often bizarre contexts. What is now needed is not yet more data (though more data are always welcome), but rather a radical re-thinking of what we already know.

This is not to say that each and every question can now be answered; we do not have to explain everything in order to explain something. Rather, we can form a broad idea of why Upper Palaeolithic people made images and, especially, what drove them into the dark caves to make hidden images. We can go further: moving beyond such generalizations, we can understand some precise specifics about caves and images. Yet, I repeat, there is still much to find out. This book does not attempt to answer each and every question that may be asked. The explanation that I propose is not a ringing down of the curtain on Upper Palaeolithic art research. On the contrary, it will, as I make plain in chapter after chapter, open up new and more searching questions.

What is missing today is not a massive collection of data or some crucial but lost piece of a jig-saw puzzle. We need a method that will make sense of the data that we already have. Methodology, the study of method, is the crucial issue. Methods should not be confused with techniques, such as radiocarbon dating, computer analysis, or the making of accurate copies of images. Method is the mode of argument that a researcher uses to reach explanatory statements. Today all researchers agree on the need for accurate techniques of dating and so forth, but they do not agree on what form of argument is likely to reach a convincing conclusion. As a result, communication between researchers who are trying to explain the phenomenon of Upper Palaeolithic cave art is at a low ebb. Misunderstandings abound, pile up and topple over into vilification. Small wonder, then, that many researchers today are resolute agnostics. They distance themselves from the explainers and concentrate on data collection.

A lack of methodology in Upper Palaeolithic art research has led to confusion of priorities. We need to have a clear idea of which questions need to be answered before others can be essayed; we need to know which questions, fascinating though they may be, can be safely left alone without impeding the progress of our explanation. This is what I try to do in this book: I circumnavigate many a reef on which debate has foundered and move on to the crucial questions that we can answer.

I begin by outlining the way in which the nineteenth-century discovery of Upper Palaeolithic art, together with the massive impact of Charles Darwins work on evolution, radically changed the way in which we think about ourselves and our place in nature and history (Chapter 1). Indeed, it is hard to overestimate the effect of these changes in Western thought.Yet, as I repeatedly point out in later chapters, pre-Darwinian ways of thinking and belief in the existence of a non-material realm, though greatly reduced, have not disappeared. At a gross level, there are still Creationists who argue for a single, miraculous moment when all of life and earth as we know it came into being by divine edict. The explanation for this uncomfortable dichotomy in modern thought lies, I argue, deep in the human brain.

To prepare for a discussion of the working of the brain, I describe the discovery of Upper Palaeolithic art (Chapter 2) and some of the highly charged debates of the time. These controversies have cast long shadows. I then examine a series of successive explanations that writers have advanced to account for this art (Chapter 3). Each was, in a sense, of its own time, for we cannot easily escape from the social and philosophical context in which we live. No doubt that contextuality is also true of the explanation that I advance. But I contest the forms of relativism,popular in some quarters today,that deny the very possibility of getting nearer and nearer to a past that really happened in the way that it did.