Acknowledgments

We thank colleagues and friends who usefully commented on parts of the text: Janette Deacon, Jeremy Hollmann, Peter Mitchell, Tom Challis, Larry Loendorf and David Pearce. Victor Biggs took us to many sites particularly those first copied by George Stow in the Eastern Cape. He and his wife Linda extended great hospitality to several field teams. Jeremy Hollmann accompanied Sam Challis to trace the Rain Snake Shelter at Sehonghong, Lesotho, and shared with us his thoughts and images of swift-people in the Western Cape. Sven Ouzman took Sam Challis to the Free State and Eastern Cape, and in particular to the site that may have inspired George Stows Blue Ostriches. Mark McGranaghan and Jamie Coreth took time from their studies at Oxford University to help conduct fieldwork in the Free State and Eastern Cape. Natalie Edwards helped create the image of the South African Rosetta Stone. Dirk and Lynette Kotze arranged site visits to several farms in the Rouxville area of the Free State. Louis Alberts helped us to search for the lost Stow site on the Aasvolberg, Zastron. We also thank landowners and field contacts: Russell Suchet, Willem and Christine Cronje, Liesel Foster, Dawn Green, Jan van Ronge, Will and Gill Pringle, Steve Bassett, Tommie Jordaan, Jack and Kollie Botha, Vaughan Victor and Qamo Thoola. Kevin Crause at the Fingerprints In Time project generously shared with us some of the results of the image-enhancing techniques that he has developed for clarifying very faint rock paintings. Azizo da Fonseca and David Duns of the South African Rock Art Digital Archive (SARADA) assisted greatly with the provision of images housed at the Rock Art Research Institute (RARI) and with permissions from other collections. We thank our colleagues at the Rock Art Research Institute: Benjamin Smith, David Pearce, Catherine Namono, John Wright, Edith Mkhabela, and colleagues Karim Sadr, Iain Burns, Peter Mitchell, Siyakha Mguni and Paolo dos Santos. Individual friends and family who have given their support to RARI and to this project: Susan Ward, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. Sam Challis thanks his wife, Kristy.

The Rock Art Research Institute is funded by the National Research Foundation, the University of the Witwatersrand, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and African World Heritage Fund.

We thank the editorial team at Thames & Hudson for their unfailing support, critical eye and meticulous editing. They brought order and consistency to our chaotic efforts and saved us much embarrassment.

COLOUR PLATES

Pl. 1 A line of eland antelope moves past low cliffs with painted rock shelters and up into the San spiritual hinterland that lies beyond the high peaks.

Pl. 2 In the 18th and 19th centuries travellers and explorers, such as the artist Thomas Baines, came across the impoverished remnants of San groups.

Pl. 3 Today, San groups living on the fringes of more complex economies still practise the trance, or healing, dance. As the women clap the rhythm, the feet of the dancing men make a rut in the sand.

Pl. 4 In the Drakensberg mountains large rock shelters beneath sandstone cliffs were occupied by the San, and they made their paintings there.

Pl. 5 On a rock in the shelter shown in the San painted a multitude of eland. Why did they think it necessary to depict so many eland?

6 In this dance clapping women stand on either side of dancing men who bend forward and support their weight on dancing sticks.

Pl. 7 A painting of a circular trance dance. The curved line may represent the dance rut or a hut in which there is a sick person and three clapping women. The pointing finger indicates the shooting of supernatural potency.

Pl. 8 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. The San painted it in various ways. It is here represented in lateral view. (see also ).

Pl. 9 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. The San painted it in various ways. In this painting, it is depicted in lateral view. (see also ).

Pl. 10 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. The San painted it in various ways: here with its head turned to look backward.

Pl. 11 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. In this painting, the San have represented it lying down.

12 Transformation is a theme in San rock art. Flying creatures are common. In this painting, a figure with a white face has emanations from the back of its neck. Its arms have white feathers.

13 Transformation is a theme in San rock art. Flying creatures are common. The swift-person in this image has a forked tail and complex wavy lines in its body.

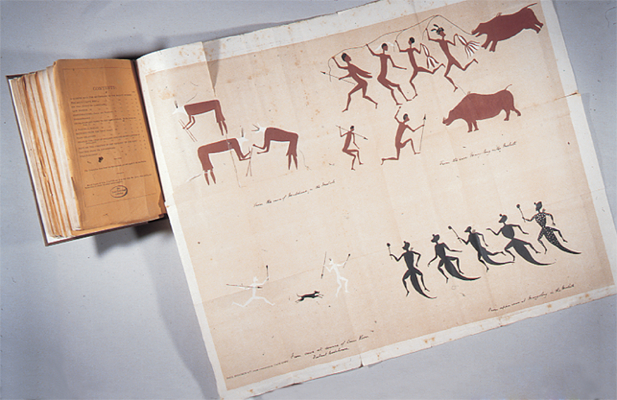

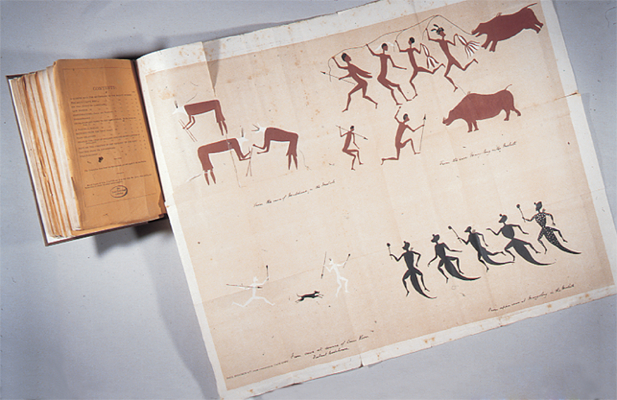

14 Joseph Orpens article A glimpse into the mythology of the Maluti Bushmen, published in 1874, illustrated four groups of San rock art images. The Sehonghong rain-capture scene [see ] is in the top right corner of the fold-out.

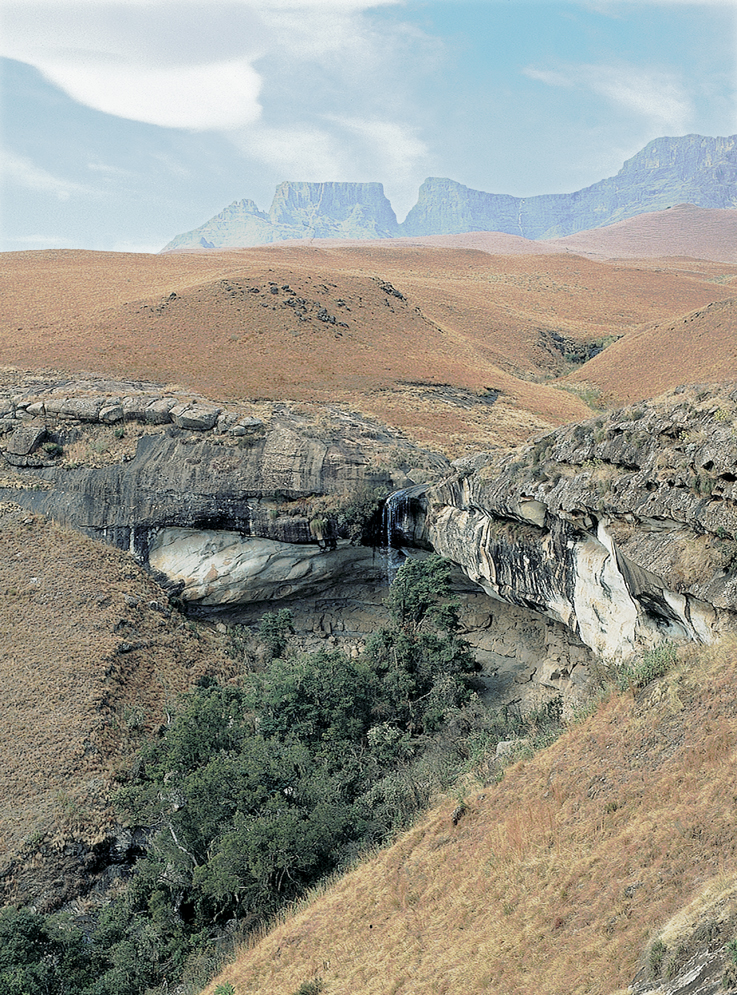

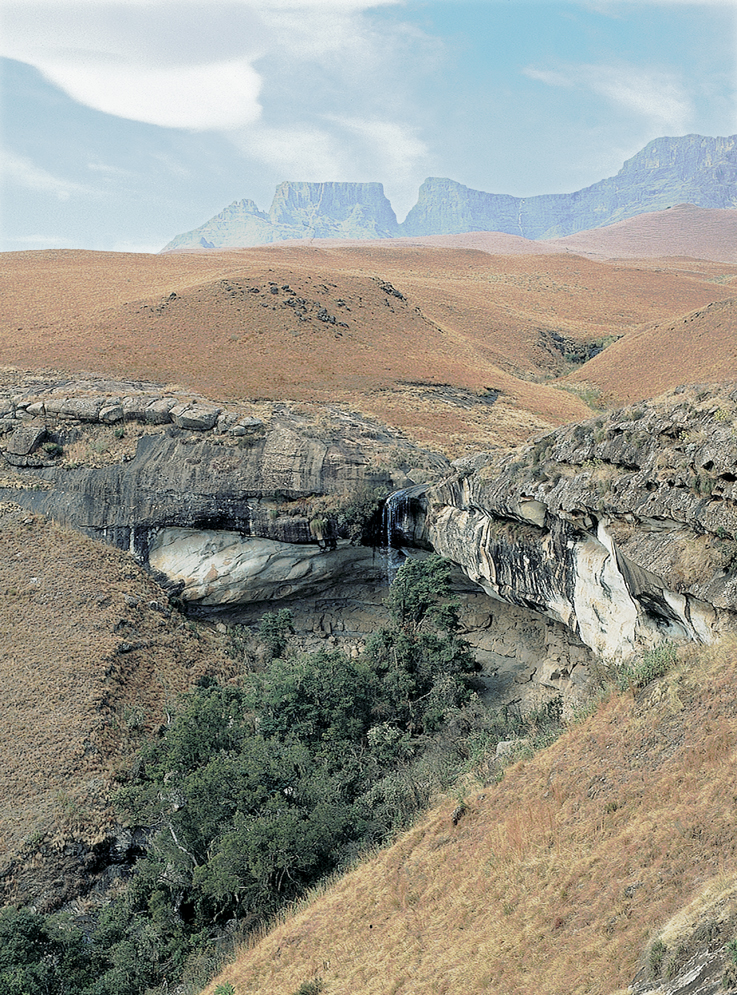

15 The high Drakensberg over which Orpens expedition climbed in 1873.

16 One of George Stows 1870s copies of rain-animals (see also ). It was through these copies that the Bleek family first learned of San beliefs about rain-making.