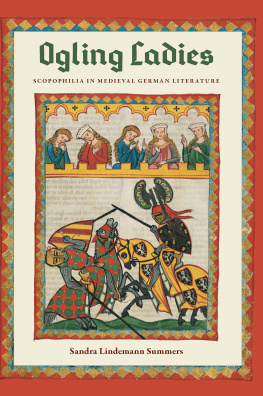

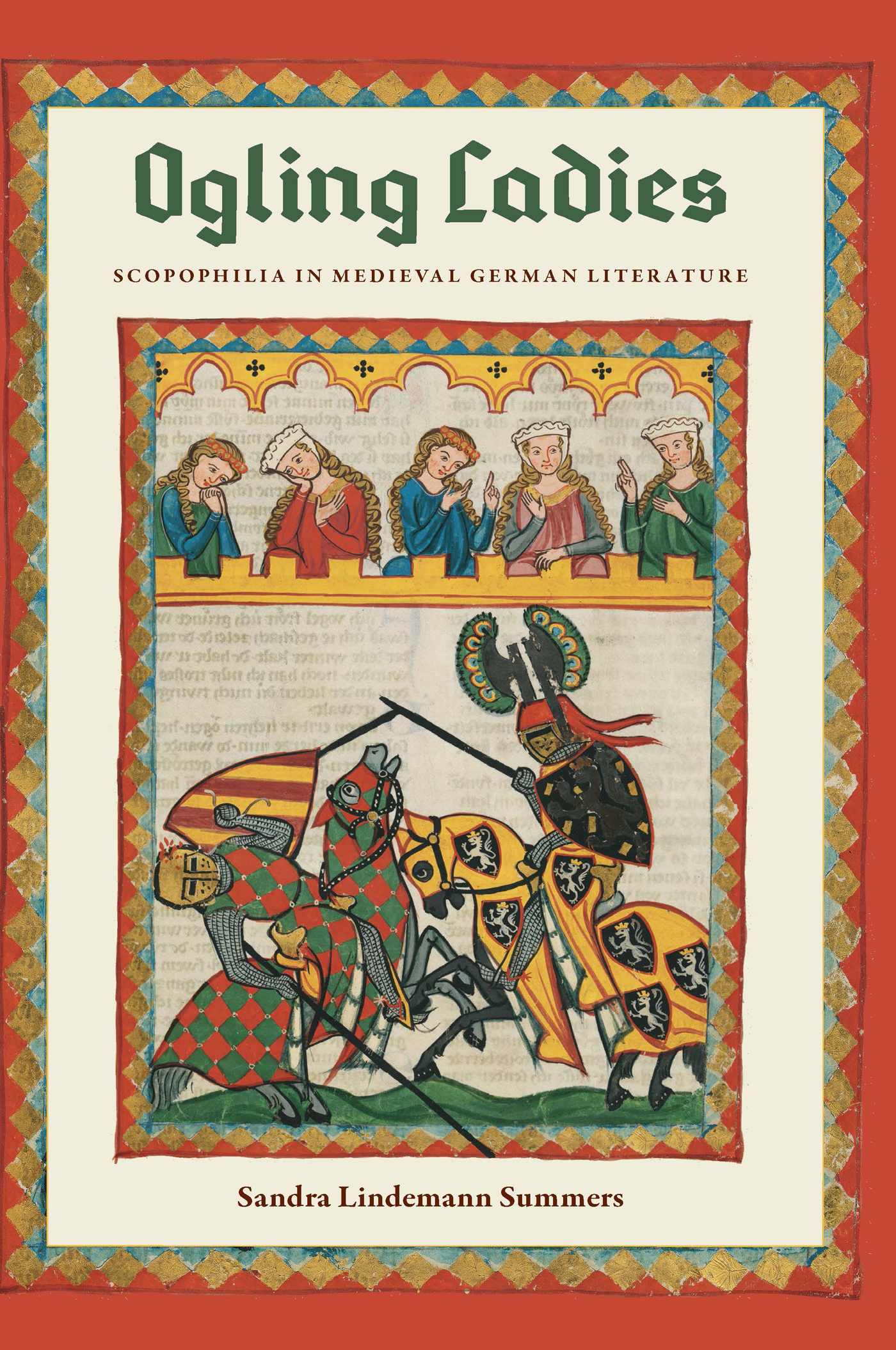

Ogling Ladies

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA

Florida A&M University, Tallahassee

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton

Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers

Florida International University, Miami

Florida State University, Tallahassee

New College of Florida, Sarasota

University of Central Florida, Orlando

University of Florida, Gainesville

University of North Florida, Jacksonville

University of South Florida, Tampa

University of West Florida, Pensacola

Ogling Ladies

SCOPOPHILIA IN MEDIEVAL GERMAN LITERATURE

Sandra Lindemann Summers

University Press of Florida

Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton

Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers/Sarasota

Copyright 2013 by Sandra Lindemann Summers

All rights reserved

Published in the United States of America. Printed on acid-free paper.

The publication of this book is made possible in part by a grant from the Department of German and Slavic Languages at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

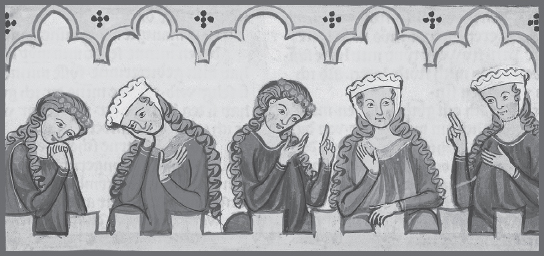

All images reproduced courtesy of the University of Heidelberg Library.

This book may be available in an electronic edition.

First cloth printing, 2013

First paperback printing, 2019

24 23 22 21 20 196 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Summers, Sandra Lindemann, 1963

Ogling ladies : scopophilia in medieval German literature / Sandra Lindemann Summers.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: An analysis of medieval literature through an exploration of the female gaze.

ISBN 978-0-8130-4418-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8130-6421-5 (pbk.)

1. German literatureMiddle High German, 10501500History and criticism.

2. Voyeurism in literature. 3. Women in literature. 4. Gaze in literature. I. Title.

PT179.S96 2013

830.9'3538dc232012046696

The University Press of Florida is the scholarly publishing agency for the State University System of Florida, comprising Florida A&M University, Florida Atlantic University, Florida Gulf Coast University, Florida International University, Florida State University, New College of Florida, University of Central Florida, University of Florida, University of North Florida, University of South Florida, and University of West Florida.

University Press of Florida

2046 NE Waldo Road

Suite 2100

Gainesville, FL 32609

http://upress.ufl.edu

To my mother, Doris Lindemann

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

An ogling woman featured in a recent television commercial: A mechanic in tight jeans is bending over a car engine while a woman standing across the street stares at his behind. In the next scene, the same woman appears in her living room with her husband, a balding, middle-aged man. She hands him a shopping bag containing the same jeans worn by the mechanic. She impatiently and breathlessly demands: Put these on. Now. I conducted an unscientific poll among friends and found that both male and female viewers of the commercial thought it funny. But what if the gender roles were reversed? What if the ogling character were a husband who surprises his wife with a skirt he had seen on a more attractive woman? Such a commercial does not exist, because it would be offensive and, more importantly, it wouldnt sell the product. Simply put, people perceive the male gaze and the female gaze as two entirely different things.

Gazing female characters caught my eye when I translated Hartmann von Aues Iwein from Middle High German into English. Especially surprising was a passage describing a young girl in the act of ogling the naked, unconscious knight Iwein. I had previously assumed that the courtly lady and not the knight would be the object of the gaze. I became curious about the gender dynamics between the characters and wanted to know more. Were there other scenes where women ogled men, where male characters, knowingly or unknowingly, became scopophilic objects of the female gaze? The answer is a resounding yes. Medieval texts are inhabited by a host of females taking pleasure in ogling male bodies.

It is my belief that this exploration of the medieval female gaze transcends medieval scholarship; it affects our understanding of the broader problematic of gender perceptions and social structuring in Western civilization. My goal as a feminist medievalist is to use medieval texts to illuminate and lay bare structures of patriarchy, documenting how they were implemented, how they worked, and why. By reading the medieval cultural artifacts through a psychoanalytic lensa strategy I explain in the introduction to this bookI will show that the representation of the female gaze is broadly split into an approved/approving motherly gaze and an undesirable critical/sexual gaze. Guiding and containing the female gaze through normative and prescriptive writing formed a complex and sometimes contradictory substructure of medieval patriarchy where women had limited agency and were traded as exchange objects.

Acknowledgments

I warmly thank Ann Marie Rasmussen, who is the main reason why I fell in love with medieval German literature. Her input and support were essential to this project from its inception to its completion. I would like to acknowledge the University Library of Heidelberg, where I was generously granted access to rare medieval manuscripts and received permission to reprint the wonderful Manesse miniatures. I thank my acquiring editor at University Press of Florida, Amy Gorelick, for her creative input and, of course, for selecting this book for publication. Jonathan Lawrence deserves special thanks for his meticulous work in editing the manuscript for publication. I sincerely thank the chair of the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages at the University of North CarolinaChapel Hill, Clayton Koelb, for supporting this project. The friendship of Halcyon Rigdon sustained me during the editorial process. Last, I owe gratitude to my husband, Thomas Stran Summers, and my daughter, Berta Jane Summers, for proofreading the original manuscript, and to my son, Erik Stran Summers, for discussing ideas on long walks with our dog Max.

Introduction

In the European Middle Ages, people did not perceive looking as a harmless, passive pastime. To the contrary, the harm that a persons gaze could cause was greatly feared; a stare was understood as an act of aggression. To be clear, the notion of the gaze as a destructive force predates medieval texts. Beautiful Narcissus, for instance, tragically loses his life because his eyes remain fixed on his own reflection for too long. Orpheus cannot control himself and defies the gods command not to look at his beloved Eurydice in Hades, losing her forever. Yet the most poignant Greek mythological example of the destructive power of the gaze is the Gorgon Medusa, who kills onlookers through a redoubled death stare. Her own dead eyes look at the mortified gazer; the twin horrors of being seen by the Gorgon while beholding her horrific severed head turn the victim to stone.

Beginning in antiquity, spanning medieval and early modern times, people, especially women, who stared openly and directly at others ran the risk of being accused of casting the evil eye. The evil-eye belief, found in many parts of the world, is the superstition that looking at someone or something can cause injury and damage; it is conceptually and linguistically linked to envy, which is the suffering felt over another persons good fortune. The

Next page