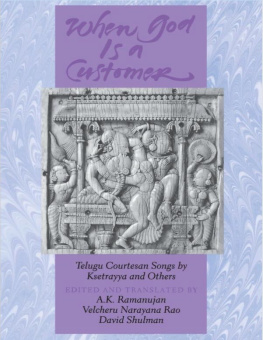

Ksetrayya - When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs

Here you can read online Ksetrayya - When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1994, publisher: University of California Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ksetrayya: author's other books

Who wrote When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

> IbYw1x

London, England 1994 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data When God is a customer: Telugu courtesan songs / by Ksetrayya and others; edited and translated by A. K. Ramanujan, Velcheru Narayana Rao, and David Dean Shulman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-520-08068-8 (alk. paper). ISBN 0-520-08069-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. 2. 2.

Telugu poetry-1800 History and criticism. 3. MusicIndia17th centuryHistory and criticism. 4. Music India18th centuryHistory and criticism. I.

Ksetrayya, 17th cent. II. Ramanujan, A. K., 1929-. III. IV. IV.

Shulman, David Dean, 1949- . PL4780.65.E5W47 1994 894.82713dc20 93-28264 CIP With deep sorrow we note the death of our beloved friend and co-author, A. K. Ramanujan, on July 13, 1993, when this book was in press.

Padams were composed throughout India, early examples in Sanskrit occurring in Jayadevas famous devotional poem, the Gitagovinda (twelfth century). 1 In South India the genre assumed a standardized form in the second half of the fifteenth century with the Telugu padams composed by the great temple-poet Tallapaka Annamacarya, also known by the popular name Annamayya, at Tirupati.2 This form includes an opening line called pallavi that functions as a refrain, often in conjunction with the second line, anupallavi. This refrain is repeated after each of the (usually three) caranam verses. Padams have been and are still being composed in the major languages of South India: Telugu, Tamil, and Kannada. However, the padam tradition reached its expressive peak in Telugu, the primary language for South Indian classical music, during the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries in southern Andhra and the Tamil region.3 In general, Telugu padams are devotional in character and thus find their place within the wider corpus of South Indian bhakti poetry. The early examples by Annamayya are wholly located within the context of temple worship and are directed toward the deity Venkatesvara and his consort, Alamelumanga, at the Tirupati shrine.

Later poets, such as Ksetrayya, the central figure in this volume, seem to have composed their songs outside the temples, but they nevertheless usually mention the deity as the male protagonist of the poem. Indeed, the gods titleMuvva Gopala for Ksetrayya, Venugopala for his successor Sarangapaniserves as an identifying signature, a mudra, for each of these poets. The god assumes here the role of a lover, seen, for the most part, through the eyes of one of his courtesans, mistresses, or wives, whose persona the poet adopts. These are, then, devotional works of an erotic cast, composed by male poets using a feminine voice and performed by women. As such, they articulate the relationship between the devotee and his god in terms of an intensely imagined erotic experience, expressed in bold but also delicately nuanced tones. Their devotional character notwithstanding, one can also read them as simple love poems.

Indeed, one often feels that, for Ksetrayya at least, the devotional component, with its suggestive ironies, is overshadowed by the emotional and sensual immediacy of the material. The Three Major Poets of the Padam Tradition Tallapaka Annamacarya (1424-1503), a Telugu Brahmin, represents to perfection the Telugu temple-poet. 4 Legend, filling out his image, claims he refused to sing before one of the Vijayanagara kings, Saluva Narasimharaya, so exclusively was his devotion focused upon the god. Apparently supported by the temple establishment at Tirupati, located on the boundary between the Telugu and Tamil regions, Annamayya composed over fourteen thousand padams to the god Venkatesvara. The poems were engraved on copperplates and kept in the temple, where they were rediscovered, hidden in a locked room, in the second decade of this century. Colophons on the copperplates divide Annamayyas poems into two major typessrngarasankirtanalu, those of an erotic nature, and adhyatmasankirtanalu, metaphysical poems.

Annamayyas sons and grandsons continued to compose devotional works at Tirupati, creating a Tallapaka corpus of truly enormous scope. His grandson Cinatirumalacarya even wrote a sastralike normative grammar for padam poems, the Sankirtanalaksanamu. We know next to nothing about the most versatile and central of the Telugu padam poets, Ksetrayya (or Ksetraya). His god is Muvva Gopala, the Cowherd of Muvva (or, alternatively, Gopala of the Jingling Bells), and he mentions a village called Muvvapuri in some of his poems. This has led scholars to locate his birthplace in the village of Muvva or Movva, near Kucipudi (the center of the Kucipudi dance tradition), in Krishna district. There is a temple in this village to Krishna as the cowherd (gopala).

Still, the association of Ksetrayya with Muvva is far from certain, and even if that village was indeed the poets first home, he is most clearly associated with places far to the south, in Tamil Nadu of the Nayaka period. A famous padam by this poet tells us he sang two thousand padams for King Tirumala Nayaka of Madurai, a thousand for Vijayaraghava, the last Nayaka king of Tanjavur, and fifteen hundred, composed in forty days, before the Padshah of Golconda. 5 This dates him securely to the mid-seventeenth century. Of these thousands of poems, less than four hundred survive. In addition to Muvva Gopala, the poet sometimes mentions other deities or human patrons (the two categories having merged in Nayaka times). 6 Thus we have poems on the gods Adivaraha, Kaci Varada, Cevvandi Lingadu, Tilla Govindaraja, Kadapa Venkatesa, Hemadrisvami, Yadugiri Celuvarayadu, Vedanarayana, Palagiri Cennudu, Tiruvalluri Viraraghava, Sri Rangesa, Madhurapurisa, Satyapuri Vasudeva, and Sri Nagasaila Mallikarjuna, as well as on the kings Vijayaraghava Nayaka and Tupakula Venkatakrsna.

The range of deities is sometimes used to explain this poets nameKsetrayya or, in Sanskritized form, Ksetrajna, one who knows sacred placesso that he becomes yet another peripatetic bhakti poetsaint, singing his way from temple to temple. But this explanation smacks of popular etymology and certainly distorts the poets image. Despite the modern stories and improvised legends about him current today in South India, Ksetrayya belongs less to the temple than to the courtesans quarters of the Nayaka royal towns. We see him as a poet composing for, and with the assumed persona of, the sophisticated and cultured courtesans who performed before gods and kings.7 This community of highly literate performers, the natural consumers of Ksetrayyas works, provides an entirely different cultural context than Annamayyas temple-setting. Ksetrayya thus gives voice, in rather realistic vignettes taken from the ambience of the South Indian courtesans he knew, to a major shift in the development of the Telugu padam. If Ksetrayya perhaps marks the padam tradition at its most subtle and refined, Sarangapani, in the early eighteenth century, shows us its further evolution in the direction of a yet more concrete, imaginative, and sometimes coarse eroticism.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs»

Look at similar books to When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book When God Is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.