Translations from the Asian Classics

Editorial Board

Wm. Theodore de Bary, Chair

Paul Anderer

Irene Bloom

Donald Keene

George A. Saliba

Haruo Shirane

David D. W. Wang

Burton Watson

THe SOunD OF THe KISS

or The Story That Must Never Be Told

Pigai Srannas Kaprodayamu

Translated from Telugu by Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman

COLumBIa UnIVerSITY PreSS NeW YOrK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2002 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50096-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pingali Surana.

[Kalapurnodayamu English]

The Sound of the kiss, or the story that must

never be told ; translated from Telugu by

Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman.

p. cm.

ISBN 0231125968 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 023112597-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

I. Title: Sound of the kiss. II. Title: Story that must never be told. III. Narayanaravu, Velceru, 1932 IV. Shulman, David Dean, 1949 V. Title.

PL4780.9.P49 K313 2002

894.827371dc21

2002025746

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

For Sanjay Subrahmanyam

aharahar-itihsa-vastu-

bahu-vidha-sambhra-dh-vibhita-ktikin

mahimnvita-v-kara-

nihita-lalita-kra-vg-vinihita-matikin

abhyudaya-paramparbhivddhig...

bhavyatan lla deamula prastutik kkucu mriy im-mah-

kvyamu suprasiddham agu gvuta nityamu sarvaloka-sam-

stavya-nija-smtin vlayu tava-ku kpan pavitra-

stra-vyasanti-dhanyam agu saj-jana-koiy anugrahambunan

This story will become famous in all countries. God, the dancing Krishna, has blessed it, and so have all learned people who are addicted to reading books.

Kaprodayamu 8.265

Many friends and scholars in India, Germany, and North America helped us in our efforts to translate Pingali Suranna. As usual with Telugu studies, our first difficulty wasin locating surviving copies of earlier printed editions of the text. Chekuri Rama Rao and Vasireddi Naveen provided us with Malladi Suryanarayana Sastris edition, the only one to document variant readings from manuscripts. Vishnubhotla Ramana sent us the two volumes of the Emesco edition with a preface and notes by Bommakanti Singaracarya and Balantrapu Nalinikanta Ravu. Vakulabharanam Rajagopal gave us speedy access to the rare Vavilla edition with annotation by Cadaluvada Jayaramasastri.

We are profoundly grateful to the early editors for their scholarly introductions and notes. Nonetheless, many questions about readings and interpretations remained. We had fruitful discussions with Prof. Kolavennu Malayavasini at Andhra University; with K. V. S. Rama Rao of Austin, Texas; and with Paruchuri Sreenivas in Grefrath, Germany, a source of unfailing bibliographic guidance and wisdom. To all of them, we offer thanks.

We are grateful for the many thoughtful suggestions about polishing the translation offered by Nita Shechet and the two anonymous readers for Columbia University Press. Students in a seminar on the Sanskrit novella at the Hebrew University in the spring semester of 2001 gave us, with their meticulous reading and enthusiasm as well as their insightful interpretations, our first assurance that the text can grip the attention of a contemporary audience.

We began work on the translation in the summer of 2000 in Jerusalem, in a flat thoughtfully provided by the Institute for Advanced Studies at the Hebrew University. That summers work was made possible by the resources put at our disposal by the University of Wisconsin in Madison. We brought the work to completion in the congenial milieu and open spaces of the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, where we had uninterrupted days to read and reread. We hope that all three institutions will find satisfaction in the fact that this unusual book is now accessible to a wider readership.

No less critical to this enterprise was the constant supply of superb sambar prepared daily by Sanjay Subrahmanyam, to whom we dedicate the translation.

No diacritical marks are used in the body of the text. Citations from Telugu and Sanskrit in the notes, the introduction, and Invitation to a Second Reading are marked in the usual scholarly style. For those who want to pronounce the names correctly, we give a list of characters, with full diacritic marks as well as brief linguistic guidance, as an appendix. All proper names and technical terms also appear in the index with full diacritical marking.

[ 1 ]

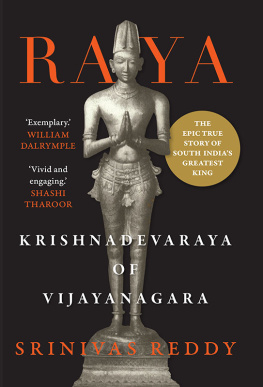

Great artists occasionally emerge together, all at once, like a goddess embodying herself in multiple forms. They may belong to a single extended moment, which they shape through their harmonic resonances in the direction of cultural innovation or breakthrough. This happened in Sophoclean Athens, for example; in Russia in the second half of the nineteenth century; in sixteenth-century Spain. It also happened in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century South India, in the area now known as Andhra Pradesh, where Telugu is spoken. In the early decades of the sixteenth century, under the patronage of a famous king, Krishna-deva-raya of Vijayanagara, Telugu poets produced masterpieces of narrative poetry, kvya, often playing with one another and echoing themes, styles, and a certain intensity of observation and description. The oustanding names are Krishna-deva-raya himself, his court-poets Peddanna and Mukku Timmanna, and, somewhat later, Tenali Ramakrishnadu and Bhattu-murtti. Together, they created a corpus of unique richness, quite distinct from any other literary production in premodern South Asia.

Toward the end of this period of volatile creativity, and still firmly rooted in the idiom of the time, a fertile poetic genius named Pingali Suranna took the impulse of literary invention in a wholly new direction. His master work, the Kaprodayamu, is translated here. We see this book as, in a certain sense, the first Indian novelthat is, as embodying the invention of a hitherto unknown genre, perhaps comparable in its sensibility and adventurous imagination to its roughly contemporaneous work in Europe, Cervantes Quixote, which is also often seen as the first modern European novel. In the Invitation to a Second Reading, we discuss the analytic features that we regard as essential to such a definition.

The Kaprodayamu is a thoroughly modern worka playful exploration of the limits of linguistic expressivity and of the ecology of available literary genres or forms; a complex psychologizing of the human mind; the elaborate working through of a plot that constantly twists and surprises the reader with its multiple perspectives and unconventional sensibility. At the same time, it is a long poem cast in the accepted modes of courtly poetry that were perfected by Surannas predecessors. Despite what we are so often told, modernity, in several specific senses, begins in South India in the sixteenth century, and this novel is one of its harbingers. It explodes nearly all the received wisdom about medieval Indian literaturefor example, the hackneyed and misleading insistence that character in premodern texts has no interiority or subjectivity and hardly undergoes change; the notion that all major texts in classical Telugu are simply translations or reworkings of Sanskrit models; the strange belief that language in these texts has no transparency and tends to the baroque or the verbose or the formulaic; the nineteenth-century accusation that classical poetic works were replete with nearly obscene sexual representations; and so on. Surannas book clearly reveals how wrong such views really are.