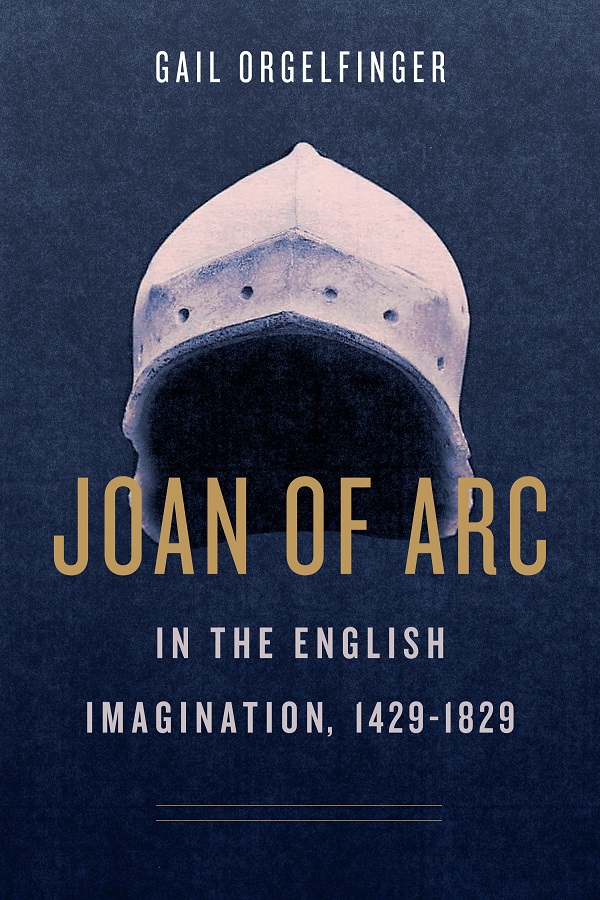

Joan of Arc in the English Imagination, 14291829

Joan of Arc in the English Imagination, 14291829

Gail Orgelfinger

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Orgelfinger, Gail Margaret, 1951 author.

Title: Joan of Arc in the English imagination, 14291829 / Gail Orgelfinger.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Explores representations of Joan of Arc in English culture from 1429 until the early nineteenth century, examining the factors that shaped retellings of her military successes and executionProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018044814 | ISBN 9780271082189 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Joan, of Arc, Saint, 14121431In literature. | English LiteratureHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC PR153.J63 O74 2019 | DDC 820.9/351dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018044814

Copyright 2019 Gail Orgelfinger

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z39.481992.

For my sister, another redoubtable Joan, and in memory of my mother.

CONTENTS

Map

Figures

My interest in Joan of Arc was initially piqued when I included excerpts from her trial testimony in a course titled The Literature of Chivalry. My students were fascinated by the words of a young woman around their own age whose life turned into legend. I became fascinated as well, and designed another course, Images of Joan of Arc. Because I taught in the English department, we focused on English and American texts about the Maid, and in the course of exploring this literature, I discovered a great deal of variety in English approaches to rewriting her story. My first debt of gratitude, then, goes to the many students at the University of Maryland, Baltimore CountyEnglish majors and nonmajors alikewho contributed their own questions and imaginations to our study of the Maid in England.

This book focuses on times gone by, but I could never have accomplished the research without the ongoing revolution in electronic resources. While I also consulted traditional monographs and articles, even microfilm, the generosity of some of the great world libraries and the efforts of individuals enabled me to read manuscripts and early printed books online in their original forms. Access to many of them was provided through the library system of the University of Maryland. Even in the twenty-first century, however, human beings remain essential for the exchange of ideas and for help and support with research. The reference and interlibrary loan staffs at the Albert Kuhn Library at UMBC were dogged and tireless in tracking down sources whenever I asked, and they succeeded every single time. Special thanks to Robin Moskal and Lidia Schechter of UMBC, as well as Paul Espinosa, Curator, George Peabody Library, Johns Hopkins University; Michael Zeliff at the McKeldin Library, University of Maryland, College Park; Catherine Maguire at the Maryland Law Library, Annapolis; and Abbie Weinberg of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

The English Department and Dresher Center for the Humanities at UMBC offered opportunities for me to speak about my early ideas and receive feedback. Funding provided by my department as well as by the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences enabled me to travel to present a number of papers exploring preliminary ideas for this book. Thanks especially to Dean Emeritus John Jeffries, and English Department Chairs Jessica Berman, Christopher Corbett, and Orianne Smith. My colleagues in the English and History departments, the Honors College, and the Medieval and Early Modern Studies Minor programnotably Raphael Falco, Thomas Field, James Grubb, Preminda Jacob, Susan McDonough, Kate McKinley, Michele Osherow, Anna Shields, and Simon Staceyalso offered much support and advice.

The International Joan of Arc Society, most of all its founder, Bonnie Wheeler, encouraged my work for over a decade. Other members of the societyand those who participated in its yearly sessions at the International Medieval Congress at Western Michigan Universitywarmly supported my efforts, and gave honest and valuable feedback: Jeremy Adams (who, sadly, died as I was completing the manuscript), Ann Astell, Stephanie Coker, Kelly DeVries, Nora Heimann, Nadia Margolis, Jane Marie Pinzino, Craig Taylor, Larissa J. Taylor, and especially Deborah Fraioli.

Throughout the long decade of thought and writing, Robin Farabaugh was a steadfast friend and excellent sounding board. Katherine Zapantis Keller and Amy Froide read the entire manuscript and gave me many fine suggestions. The anonymous reviewers for Penn State University Press helped me make this a better book than I could have accomplished on my own. Working with the Press has been a thoroughly rewarding experience, and I owe special gratitude to my editor Eleanor Goodman, who patiently listened to yearly updates and provided both frank and empathetic support.

Thanks are not adequate for my chief sustainer, supporter, and patient listener, Chuck Hanna, my husband and partner these forty years and more.

During the first session of her trial, Joan was asked her name and surname, and she answered, Where she was born she was called Jeannette, and in France, Jeanne; and she knew nothing of her surname. She did not use her fathers or mothers informal surnames, Darc and Rome. She did not call herself The Maid of Orleans. Thus, in a book about English perceptions of the Maid, I shall use the English version of her name, Joan, unless quoting directly from a French or Latin source or referring to a fictional character.

In general, I have silently expanded contractions in both Latin and English texts. Otherwise, except for replacing // with /th/, /vv/ with /w/ and substituting /j/ for /i/, /u/ for /v/, and vice versa for readability, I have retained original spellings.

Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own.

Fatal to England, Fortunate to France;

Of thone I curbd the surly Arrogance;

And with my Lance the tottring Throne sustaind

Of thother Realm, whose Freedome I regaind.

The smoakie Ordures of the burning Pile

Could not my spotless Innocence defile;

And my opprobrious Death more mischief brought

To those that causd it, then my Arm that fought.

Pierre Le Moyne, Sonnet, The Gallery of Heroick Women, 1652

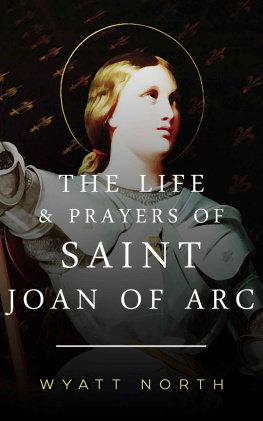

Standing tall in golden armor and gazing heavenward past the point of her raised sword, the statue of Coming just five years after the end of World War I, and three years after Joans canonization by the Catholic Church, this acknowledgment would seem to place a period on a centuries-long evolution of English opinion.