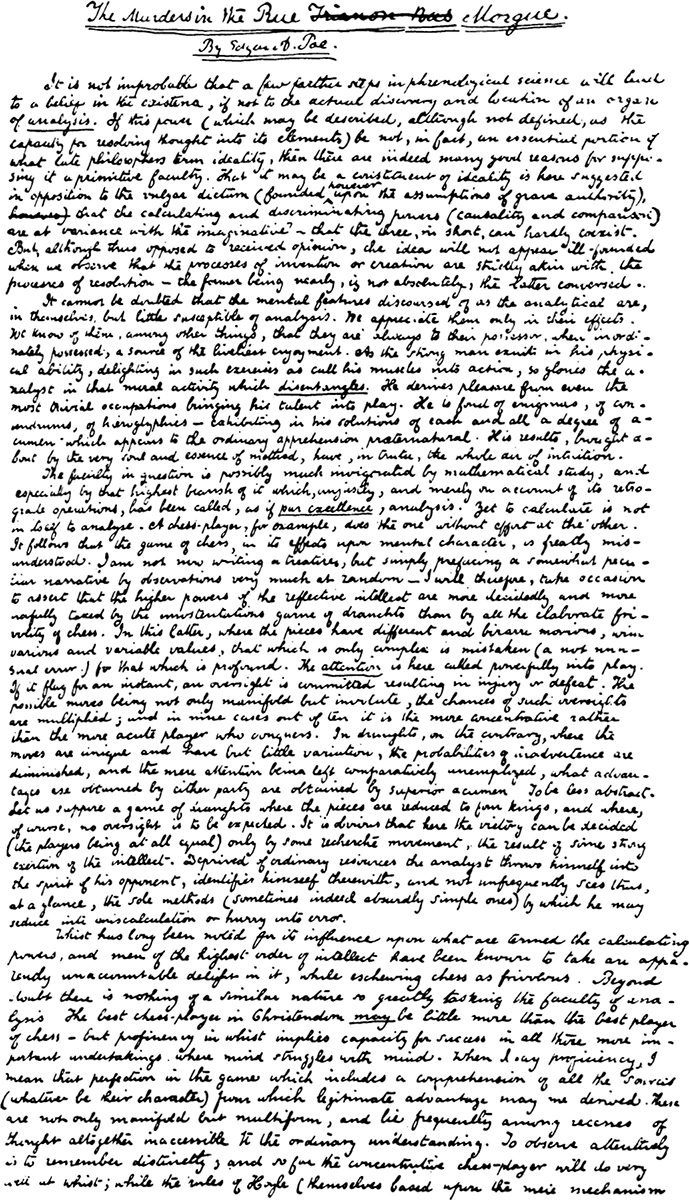

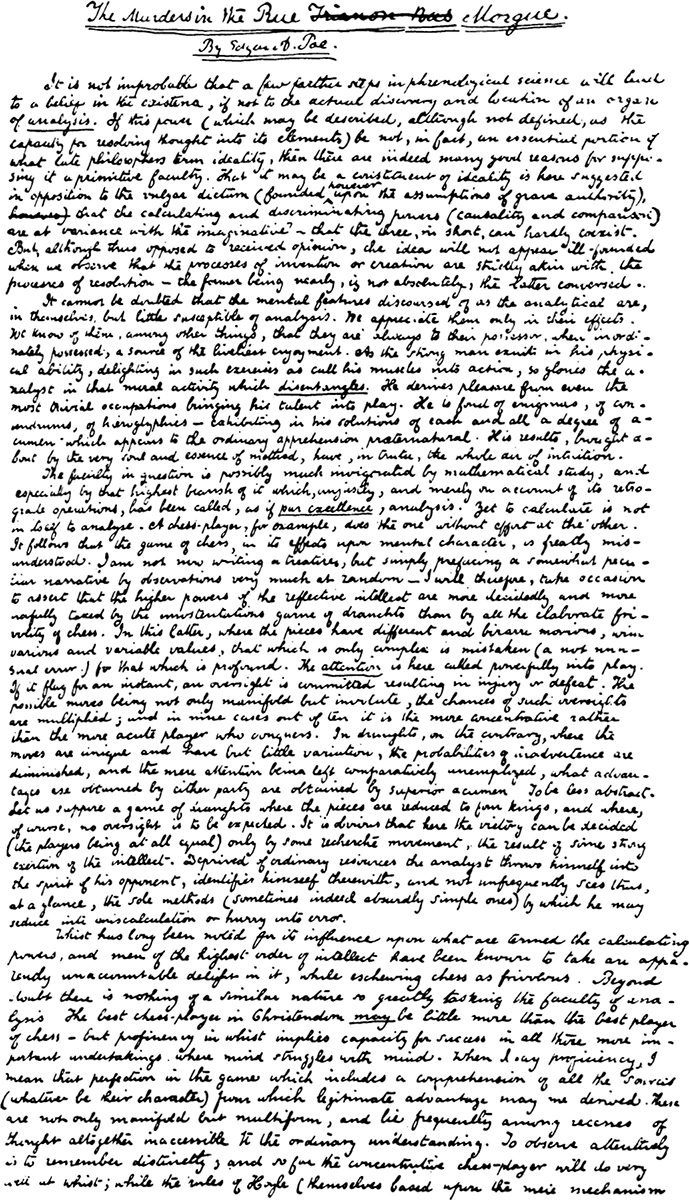

THE FIRST DETECTIVE STORY

First page of the original manuscript of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue."

(Reproduced by special permission of the Board of Trustees of the Drexel Institute of Technology, Philadelphia.)

To

M.S.H.

and

J.E.H.

Copyright

Copyright 1941 by D. Appleton-Century, Inc.

Copyright renewed 1968 by Howard Haycraft

Copyright 1951 by Mercury Publications, Inc.

Copyright renewed 1979 by Davis Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Reprinted by permission of the estates of Frederick Dannay and Manfred B. Lee and by arrangement with Curtis Brown, Ltd.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2019, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1951 by Mercury Publications Inc., New York, which was an updated and enlarged edition of the work first published by the D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., New York, 1941.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Haycraft, Howard, 1905-1991, author.

Title: Murder for pleasure : the life and times of the detective story/Howard Haycraft.

Description: Mineola, New York : Dover Publications, Inc., 2019. | "This Dover edition, first published in 2019, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1951 by Mercury Publications Inc., New York, which was an updated and enlarged edition of the work first published by the D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., New York, 1941"Title verso. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018037704| ISBN 9780486829302 | ISBN 0486829308

Subjects: LCSH: Detective and mystery storiesHistory and criticism. Detective and mystery storiesBibliography.

Classification: LCC PN3448.D4 H3 2019 | DDC 809.3/872dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037704

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

82930801 2019

www.doverpublications.com

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

FOREWORD

The detective story is the normal recreation of noble minds.

PHILIP GUEDALLA

* * *

My theory is that people who don't like mystery stories are anarchists. REX STOUT

WHEN Nazi Luftwaffe squadrons unleashed their wanton fury on London in the late summer of 1940, initiating to their own consternation a deathless epic of human courage and resistance, they also drove a city of eight million souls beneath the earth's surface for nightly refuge. After the first shock of a kind of battle new in the annals of warfare had passed, life underground began to take on some of the aspects of normality. One of the earliest harbingers of rehabilitation was the appearance of books in the fetid burrows while the bombs rained overhead. What volumes, asked curious Americans from the comfortable security of their homes, could men and women choose for their companionship at such a time? The answer was soon forthcoming in dispatches from the beleaguered capital, telling of newly formed "raid" libraries set up in response to popular demand to lend detective stories and nothing else. The implications contained in this circumstance, as applied to the underlying appeal of the detective novel, might easily constitute a superior essay in themselves (and are perhaps unfathomable at that). But surely no more striking illustration could be found of the vital position which this form of literature has come to occupy in modern civilized existence, for whatever reasons.

That detective stories are a mere hundred years old seems, in fact, beyond belief; in the same sense that imagining daily life without the telephone or the radio strains all credulity. For to-day it is a matter of sober statistical record that one out of every four new works of fiction published in the English language belongs to this category, while the devotion the form has managed to arouse in millions of men and women in all walks of life, the humble and the eminent, has become a latter-day legend.

No less a qualified authority than Mr. Somerset Maugham has recently ascribed this state of affairs to the fact that "the serious novel of to-day is regrettably namby-pamby." The charge is outside the province of the present volume and can not be examined here. But Mr. Maugham goes on, at least half seriously, to predict the day when the police novel will be studied in the colleges, when aspirants for doctoral degrees will shuttle the oceans and haunt the world's great libraries to conduct personal research expeditions into the lives and sources of the masters of the art.

Whatever the merits or likelihood of these suggestions, the surprising circumstance is that no adequate factual or analytical history of this movementso clearly the outstanding literary phenomenon of modern timesyet exists. There have been, of course, the excellent but brief critical studies by Dorothy Sayers, Willard Huntington Wright, and E. M. Wrong; and the longer but relatively inaccessible (and, it must be said, rather academic) treatises of H. Douglas Thomson, Rgis Messac, and Franois Fosca, the first published only in England and now out of print, and the latter two available only in French. These, together with a handful of prefaces, and a larger but widely scattered and uncoordinated body of magazine articles, and one or two "how-to-write-it" manuals, constitute the entire published literature on one of the most vigorous and virile types of all contemporary writing. A form which, to many readers, has come to occupy the solacing spot which Robinson Crusoe held in Gabriel Betteredge's affections: a "friend in need in all the necessities of this mortal life"the one dependable and unfailing anodyne in a world so realistically murderous that fictive murder becomes refuge and retreat!... The present book has been undertaken in the hope of at least partially remedying this deficiency: of providing a reasonably readable and useful outline of the main progress of the detective story from Edgar Allan Poe to the present moment.

Throughout the book, the reader will find, emphasis has been placed on the actual and factual rather than the theoretical phases of the subject; with side excursions, when space has permitted, into those fascinating if trivial problems of idiosyncrasy and mannerism so dear to the heart of the true enthusiast. In short, the underlying object of the work has been pleasurefor reader and writer alike.

In making any such book, the problem of exclusion must be, necessarily, more difficult than that of inclusion. The question of just what constitutes a detective story will be considered at some length in the body of the work. For the present we can do no better than repeat again John Carter's useful and often quoted dictum, as the basis upon which authors and their various works were accepted or rejected: "If we decide, as surely we must, that a detective story within the meaning of the act must be mainly occupied with detection and must contain a proper detective (whether amateur or professional), it is clear that mystery stories, crime stories, spy stories, even Secret Service stories, will have to be excluded unless any particular example can show some authentic detective strain."

Thus, the volume in hand has been restricted to the bona-fide, the "pure," detective story and its craftsmenas distinguished (to quote Carter again) from "mere mystery on the one hand, and criminology on the other." Regrettably, it has been impossible to discuss at length all the competent authors who come legitimately under even this rule. Their number has become so increasingly great within recent decades that only a veritable encyclopedia could deal with them adequately. Too, this volume is of necessity concerned less with literary merit per se than with setting forth the history and evolution of detective fiction as a recognizable form. This has made the basis of choice chiefly historical rather than appreciative. Hence, detailed discussion has been limited to those practitioners whose works, in the writer's opinion, have most significantly influenced the progress of the police romance throughout the years, either in technique or in popularity. The premise has sometimes meant the inclusion of authors of no very great distinction in themselves, and the omission of others (including many personal favorites) whose achievements, judged by purely literary standards, might be considered of a higher order. Nevertheless, the attempt has been made to recognize if only in the several lists and indexes most of the authors who have contributed ably and consistently to the form.

Next page