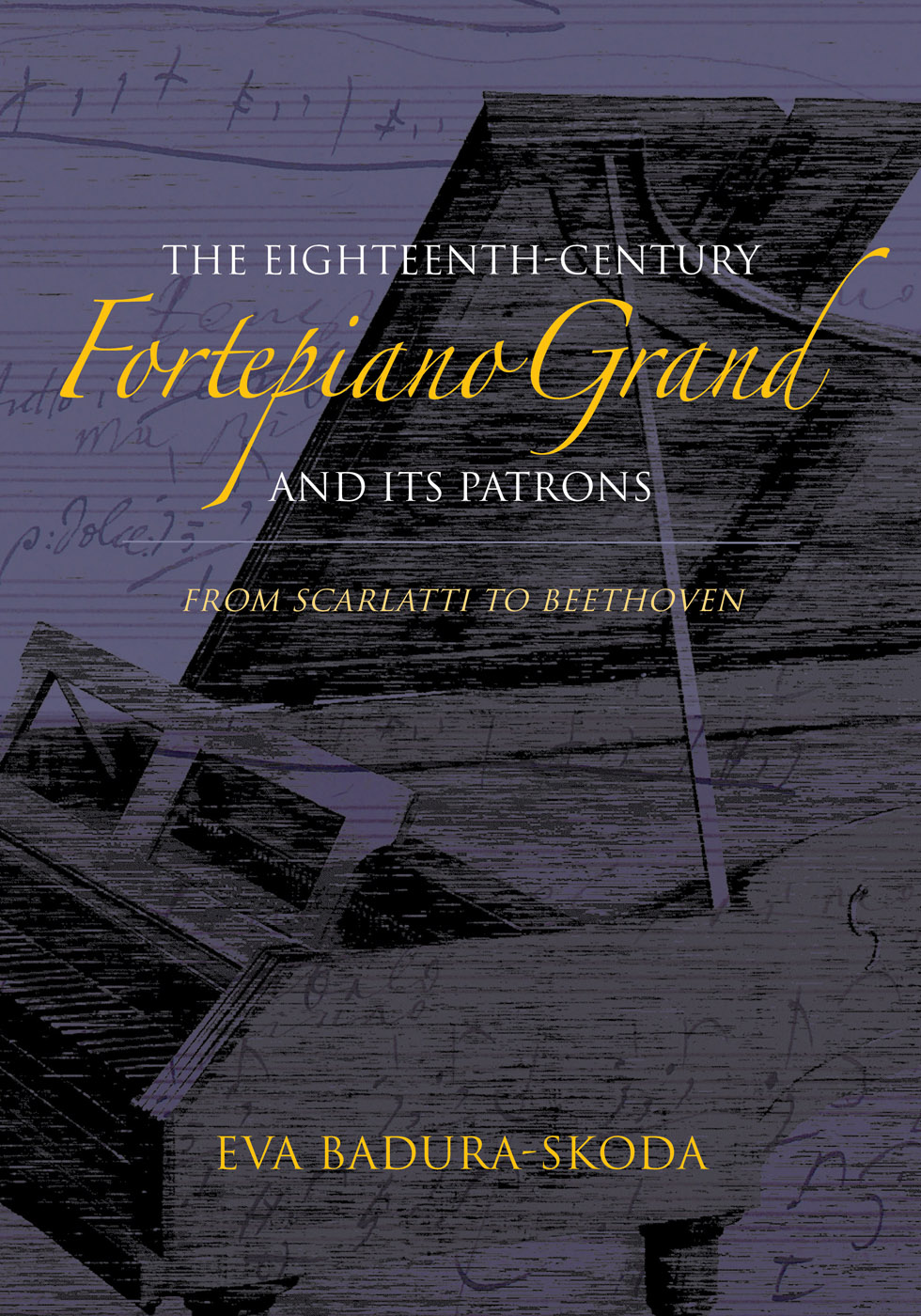

THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORTEPIANO GRAND and ITS PATRONS

THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY Fortepiano Grand AND ITS PATRONS

FROM SCARLATTI TO BEETHOVEN

EVA BADURA-SKODA

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by Eva Badura-Skoda

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Badura-Skoda, Eva, author.

Title: The eighteenth-century fortepiano grand and its patrons from Scarlatti to Beethoven / Eva Badura-Skoda.

Description: Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019218 (print) | LCCN 2017021199 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253022646 (e-book) | ISBN 9780253022639 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: PianoHistory18th century.

Classification: LCC ML 650 (ebook) | LCC ML650 .B33 2017 (print) | DDC 786.2/1909dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019218

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18 17

CONTENTS

PREFACE

ONE PURPOSE OF THIS BOOK is to draw the attention of musicians and music historians to the implications and consequences of misunderstandings of terms and some other misperceptions. Another is to present historical insights that are results of my lifelong interest in eighteenth-century music and its performance and of my care for a collection of historical keyboard instruments. This book, however, is not intended to become a History of the Piano-Forte in the Eighteenth Century. A reader should not expect therefore to find here such a comprehensive historythe book does not pretend such completeness. In addition, I should mention that my historiographical approach is not a mere positivistic one; my intention has always been to question the plausibility of various assumed but somehow odd research results as presented in some books or articles. Documents can be sometimes misleading if taken too literally or misunderstood in another way. Problems stemming from terminological ambiguities caused by incomplete source survival are sometimes difficult to understand and to explain; it needed a repeated careful study of all known sources as well as considerations of plausibility to explain the proposed solutions for obvious riddles not yet generally considered solved. Some of those riddles require a new discussion.

This book was planned many years ago. In an article that appeared in 1980, Prolegomena to a History of the Viennese Fortepiano,eighteenth century is not correct; in the twentieth century these terms referred to plucked instruments only, but in the eighteenth century they referred solely to the outer form of stringed keyboard instruments, a fact I understood from studying many eighteenth-century documents. Especially during the first half of the eighteenth century this form was that of a harp or a wing (in German, Flgel). Besides, before 1750, there must have been a common understanding that all wing-shaped pianofortes, or Flgel, belonged to the family of harpsichord instruments. The term hammer-harpsichord was in use in England during Charles Burneys lifetime. For a book written in English it is therefore appropriate to point to this clearly expressed fact in Burneys writings. Burneys use of harpsichord helps us understand that it referred to harpsichords with quills as well as harpsichords with hammers (or hammer-harpsichords as Burney called the new pianofortes in his historical survey). These two kinds of harpsichords were usually both called simply harpsichords. The very term hammer-harpsichord certainly proves that there is a difference between Burneys understanding of the term and that of the many modern musicians and musicologists who still wrongly assume that an eighteenth-century harpsichord had only quills plucking the strings and could not possibly have had hammers touching the strings. The eighteenth-century meaning of harpsichord in its broader generic sense as a large stringed keyboard instrument, regardless of whether it had quills or hammer actions or both, has been acknowledged in the meanwhile by an increasing number of musicologists and also by some musicians; but the great majority of present-day musicians are still not aware of this fact and its implications. Therefore, I decided to begin the introduction to this book with Burneys statements that demonstrate clearly the differing eighteenth-century meaning of harpsichord, thus making apparent that it is not my subjective personal belief but a historical fact and an objectively proven reality. In Burneys time harpsichord could also mean a hammer-harpsichord.

When in 1980 I tried for the first time to publish facts that I thought proved beyond doubt that for eighteenth-century musicians such terms as harpsichord or cembalo simply referred to their wing-shaped form of stringed keyboard instruments, regardless of whether the strings were plucked or made to vibrate with the help of tangents or hammers, I was myself not yet aware of the important implications of this misunderstanding among musicians. Indeed, it took me many years to see how this terminology had caused far-reaching misunderstandings. Often a slightly distorted and lopsided historical view (Geschichtsbild) was one of the unfortunate results of the misunderstanding. Today, even those colleagues who concur with the fact that the mentioned terms have a different meaning in modern times than they had in the eighteenth century do not realize that some relevant strong (though often unconscious) prejudices were created long ago by the misperception and are still influential. What does the title of a composition such as Harpsichord Sonata or Sonata da Cembalo mean? We all (me included) still have to fight our probably unnoticed subconscious assumption that a harpsichord is an instrument with quills when asking ourselves which eighteenth-century sonatas were obviously composed for quilled harpsichords and which may have already been intended to be played primarily on a hammer-harpsichord if such an instrument was available. Traditional understanding is a mighty force against any change of perception. This books writing and its long gestation will not have been in vain if in the future, when we encounter the terms harpsichord, clavecin, or cembalo in an eighteenth-century context, we will force ourselves to ask whether perhaps a hammer-harpsichord was meant; in a few cases we might feel obliged to change our old perception.

I considered it necessary to discuss the consequences of this evidence of a wrong perception in a book and not only in an article because there are still far too many musicians and music lovers around who have no idea about this eighteenth-century terminology problem. During the last decades, however, other tasks and problems had left me little time for planning the final outline for a book. A few chapters, written before 1990, became shorter articles and informed a script for a TV documentary,

Next page