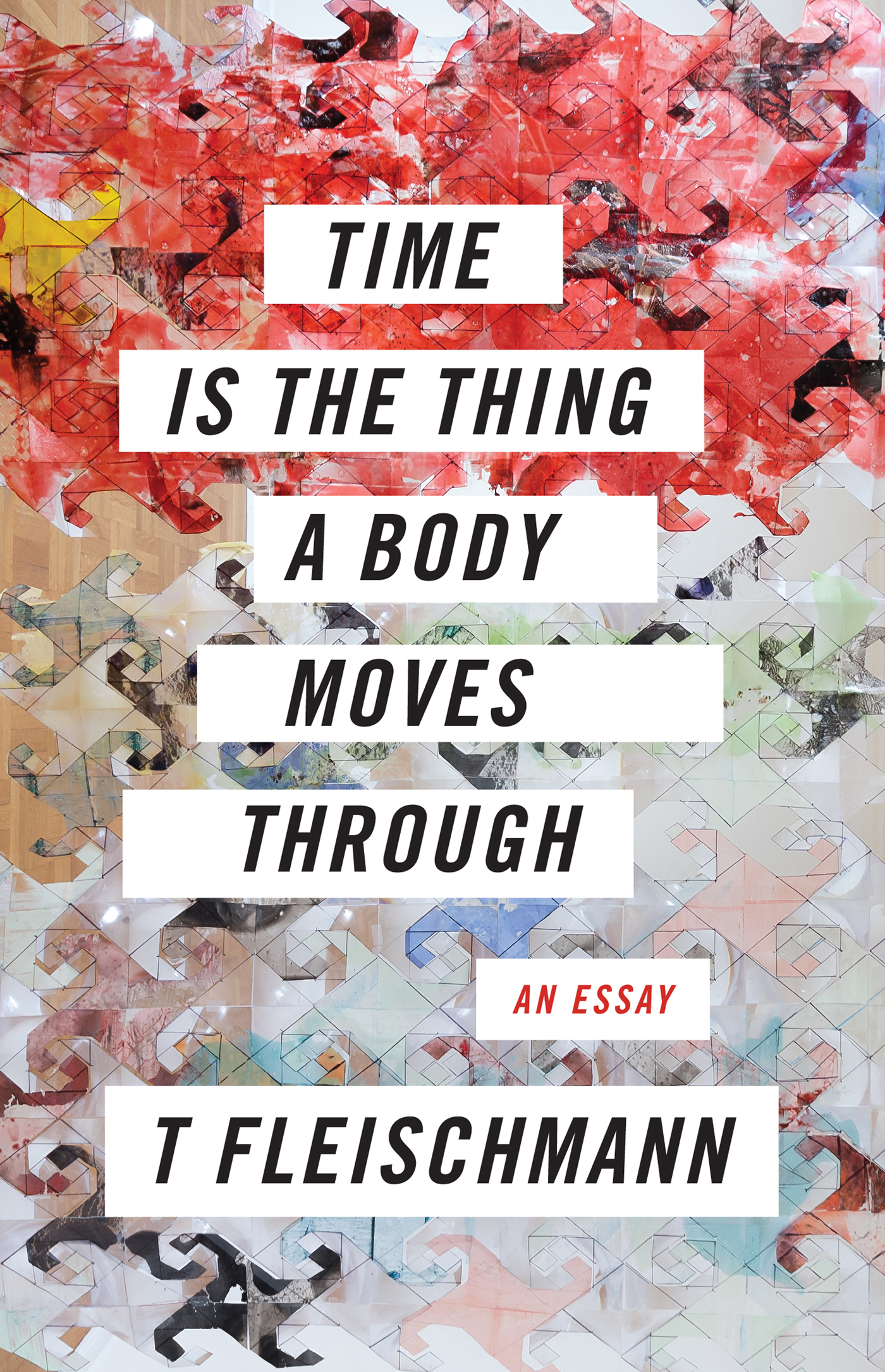

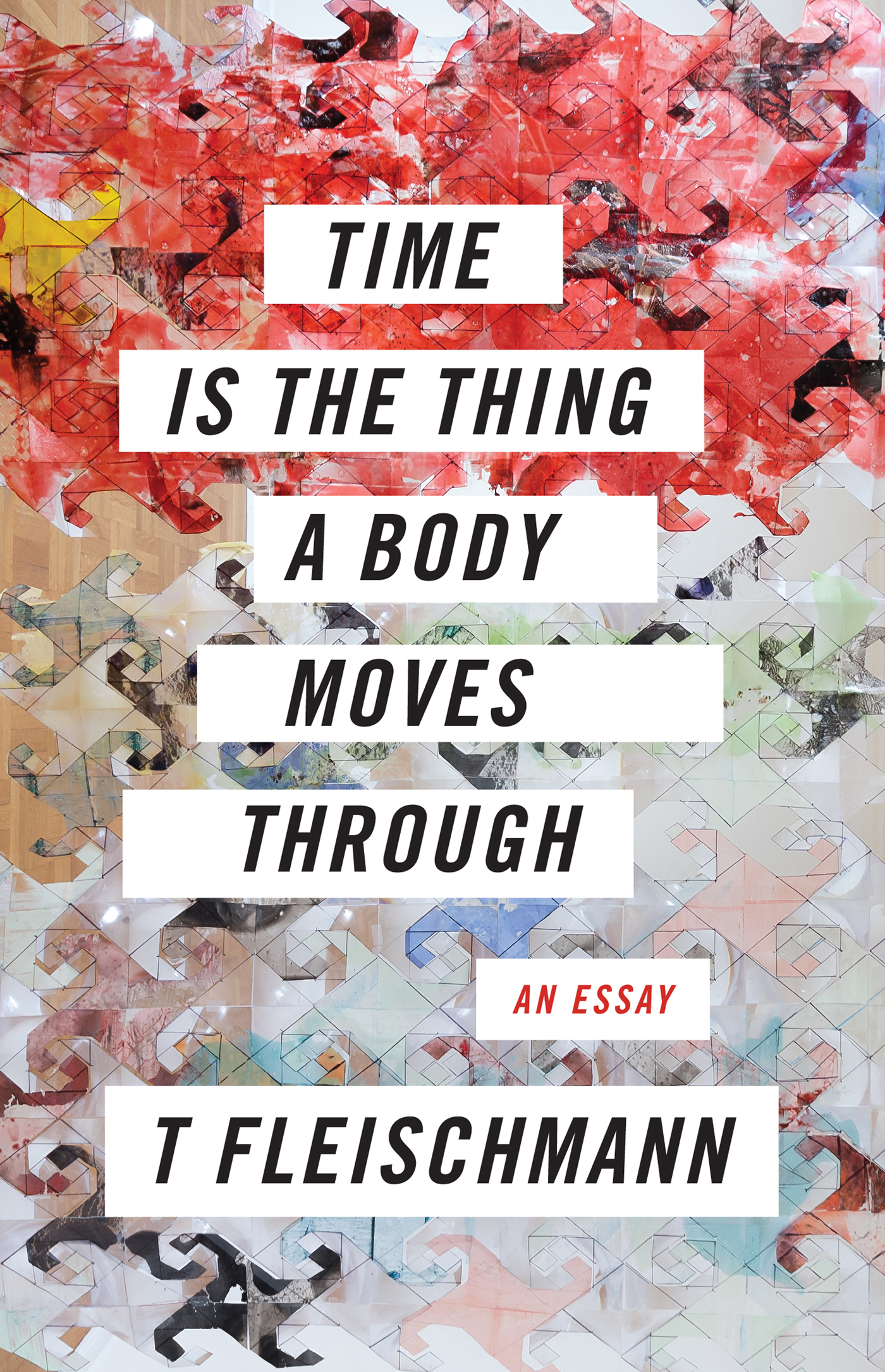

TIME IS THE THING A BODY MOVES THROUGH

TIME IS THE THING A BODY MOVES THROUGH

T FLEISCHMANN

Copyright 2019 by T Fleischmann

Cover art, Ommatidium Oma-tittie-ah Quilt, 2016 by Stevie Hanley

Photograph of cover art by Robert Chase Heishman

Cover design by Kyle G. Hunter

Book design by Rachel Holscher

Author photograph May Allen

Coffee House Press books are available to the trade through our primary distributor, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution, .

Coffee House Press is a nonprofit literary publishing house. Support from private foundations, corporate giving programs, government programs, and generous individuals helps make the publication of our books possible. We gratefully acknowledge their support in detail in the back of this book.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Fleischmann, T., 1983 author.

Title: Time is the thing a body moves through / T Fleischmann.

Description: Minneapolis : Coffee House Press, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018040653 (print) | LCCN 2018059169 (ebook) | ISBN 9781566895552 (ebook) | ISBN 9781566895477 (trade pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Fleischmann, T., 1983 | Authors, American21st centuryBiography

Classification: LCC PS3606.L453 (ebook) | LCC PS3606.L453 Z46 2019 (print) | DDC 818/.603dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018040653

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 191 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

TIME IS THE THING A BODY MOVES THROUGH

CONTENTS

SUMMER

I leave Buffalo when the moon is still out, and on the long bus ride south I find myself unable to read. I often cant read on transit, the presence of so many other people demanding a half-attention that interferes with the attention a book requires. Instead, I look at Scruff, where the hills and plateaus offer just blips of men. Most of them are stationary, so the buss crawl puts them at steadily increasing or decreasing proximities, of two hundred miles and then one hundred and eighty, of one hundred and eighty and then one hundred and sixty, of eighty and then ninety. One guy seems to travel a similar path, a similar speed, either following me or preceding me, thirty-one miles away, thirty, thirty-one.

On the grid I keep checking an account that features three gray-haired men, their arms around one another, each a bottom. Top who wants to join our family. Who does like to play games and believes you can love more than one person. Is ok with having sex only inside our group and so on. Further into the profile, each describes himself, although these short paragraphs seem only to further conflate their livesthey all like hanging out, dogs, and especially their pugs. I like to read, write, and relax with my boyfriends, one says. Another, in a typo, says he likes to cook and do choirs. They are all smiling, beaming really, but the one in the middle of their embrace, the shortest one, his smile is the widest.

Bottoms seeking their top, I imagine them all in a king-sized bed, asses in the air, waiting. And when the two met the third: the realization that he, too, was a bottom, and the disappointment that must have given way to familial, romantic love. Does the newest bottom fear he is there only to heighten the appeal to their eventual topnot there as a he, but as one of them? He must run to the other rooms to get the lube, their double-headed dildos (but this an intense joy, so a top might puncture it; it is good they are isolated on this plateau).

I came to Buffalo to see my friend Simon in his new home, but also to visit him, a guy I love in my own weird way, without the potential of sex charging our time. Well never have sex again then, well just take that off the table, I said over the phone a month earlier, years of occasional fucking ended with relief instead of histrionics. These expectations cleared up, I arrived to find his body the same muscled, pale thing it had always been, his smile the same quick grin and his jokes the same bleak insights. I settled into this new arrangement, although the relief from touch felt to me like an ache, or like the auditory hallucination that would linger after I listened to the same song on a loop all afternoon.

We wandered the streets of Buffalo gay pride as two close friends, friends who knew each other to be just that as we played pool, which we did, poorly and drunkenly. We held the doors open for one another and lit our own cigarettes. I insisted on a fancy meal, my treat, and we followed cocktails with cocktails, and when our feet touched under the table it seemed only to underscore what we would not be doing that evening, rather than tantalizing the possibility of what we might do. We still laughed and we still complimented each others shirts and we still talked books on our long walks. Friendship was an easy enough place, our relation to one another locatable in languagea friend visiting from out of town, Simon explained to the men who hit on him at bars. But we had always been friends, a word that reduced our odd joining to something less than what it was.

Before boarding the bus, I sat on Simons bed and he sat a few feet away, at his kitchen counter. We shared a carafe of coffee with Democracy Now! humming on a radio by the window. We talked about his large taxidermy dog, Germanard, a German shepherd who had died protecting his former owner during a home invasion and that Simon had put in storage. He got ready as I got ready, and he went off to the coffee shop where he worked, and I went to the bus, leaving while the morning held its chill, then taking my jacket off and crumpling it into a pillow to use on board.

Scruff offering me nothing, I scrunch up into my laptop and open the thing Im writing, a project I began in the erotic vibrations of my friendship with Simon several years ago. Its not that I believed our relationship transcended anything, exactly, or that it would become anything but what it waswe were always clearly a pair, we two friends. I was writing instead to see where my excess of desire would go, when a simple thing like falling asleep with my arm across a guy I loved meant I would buzz with anticipation of falling asleep all day. I tried to write in such a way that there would be room for that buzzing along my words, even if I did not always find room for it in my life.

For the month of July, I stay in a room in an apartment in the

Lefferts Gardens neighborhood of Brooklyn.

There are two other people who live here, one a close friend

and one an acquaintance.

I share the room with a third friend, Simon.

He, like me, thinks often of the breaking of ice or glass.

In the living room is a small round table with a lamp at its center.

Surrounding the lamp is a pile of individually wrapped candies,

thirty or forty maybe, all of them a crisp and glistening blue.

They are quiet until you touch them, and then they crinkle.

The first time I walked up to Untitled (Portrait of Ross in

L.A.) I stood before the piece by Felix Gonzalez-Torres for two

or three minutes, a few feet back.

A friend had earlier explained it to me, so I knew I was

allowed to step forward and take a piece of the candy.

I selected one wrapped in bright yellow foil.

I knelt, lifted it, and fingered it for a moment before

unwrapping.

I placed it in my mouth.

I sucked at the candy as I continued to look at the pile, slightly

Next page