Pink Moon

Praise for the series:

It was only a matter of time before a clever publisher realized that there is an audience for whom Exile on Main Street or Electric Ladyland are as significant and worthy of study as The Catcher in the Rye or Middlemarch. The series, which now comprises 29 titles with more in the works, is free-wheeling and eclectic, ranging from minute rock-geek analysis to idiosyncratic personal celebration The New York Times Book Review

Ideal for the rock geek who thinks liner notes just arent enough Rolling Stone

One of the coolest publishing imprints on the planetBooks/ut

These are for the insane collectors out there who appreciate fantastic design, well-executed thinking, and things that make your house look cool. Each volume in this series takes a seminal album and breaks it down in startling minutiae. We love these. We are huge nerdsVice

A brilliant serieseach one a work of real loveNME (UK)

Passionate, obsessive, and smartNylon

Religious tracts for the rock n roll faithfulBoldtype

[A] consistendy excellent seriesUncut (UK)

Wearent naive enough to think that were your only source for reading about music (but if we had our waywatch out). For those of you who really like to know everything there is to know about an album, youd do well to check out Continuums 33 1/3 series of booksPitchfork

For reviews of individual titles in the series, please visit our website at www.continuumbooks.com and 33third.blogspot.com

Also available in this series:

Dusty in Memphis by Warren Zanes

Forever Changes by Andrew Hultkrans

Harvest by Sam Inglis

The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society by Andy Miller

Meat Is Murder by Joe Pernice

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn by John Cavanagh

Abba Gold by Elisabeth Vincentelli

Electric Ladyland by John Perry

Unknown Pleasures by Chris Ott

Sign O the Times by Michaelangelo Matos

The Velvet Underground and Nico by Joe Harvard

Let It Be by Steve Matteo

Live at the Apollo by Douglas Wolk

Aqualung by Allan Moore

OK Computer by Dai Griffiths

Let It Be by Colin Meloy

Led Zeppelin IV by Erik Davis

Armed Forces by Franklin Bruno

Exile on Main Street by Bill Janovitz

Grace by Daphne Brooks

Murmur by J. Niimi

Pet Sounds by Jim Fusilli

Ramoms by Nicholas Rombes

Endlroduting by Eliot Wilder

Kick Out the Jams by Don McLeese

Low by Hugo Wilcken

In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Kim Cooper

Music from Big Pink by John Niven

Pauls Boutique by Dan LeRoy

Doolittle by Ben Sisario

Theres a Riot Goin On by Miles Marshall Lewis

Stone Roses by Alex Green

The Who Sell Out by John Dougan

In Utero by Gillian Gaar

Loveless by Mike McGonigal

Bee Thousand by Marc Woodworth

The Notorious Byrd Brothers by Ric Menck

Court and Spark by Sean Nelson

London Calling by David L. Ulin

Daydream Nation by Matthew Stearns

Peoples Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm by Shawn Taylor

69 Love Songs by LD Beghtol

Use Your Illusion I & II by Eric Weisbard

Songs in the Key of life by Zeth Lundy

Rid of Me by Kate Schatz

Achtung Baby by Stephen Catanzarite

If Youre Feeling Sinister by Scott Plagenhoef

Forthcoming in this series:

Swordfisktrombones by David Smay

Lets Talk About Love by Carl Wilson

and many more

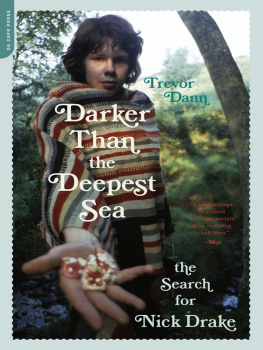

Pink Moon

Amanda Petrusich

Contents

1.1 Saw It Written

On Saturday, November 23, 1974, Nick Drake retired to his bedroom at Far Leys, his parents bucolic, red brick estate in Tanworth-in-Ardena small, preposterously pastoral village in the county of Warwickshire, just southeast of Birmingham, England. Drake had been staying at Far Leys, on and off, since 1972. According to his first biographer, Patrick Humphries, Drakes bedroom was a tiny, simple room, with a small circular window in one corner, furnished with a cane chair, a single bed, an old wooden desk, and a still-life painting of a vase of flowers. It was neat, austere, contained. An alcove bookshelf housed D. H. Lawrence, Hamlet, Browning, Shakespeare, Blake.

At some point before dawn on Sunday, November 24th, Drake left his bedroom, ambled into the kitchen, shook some cornflakes into a bowl, splashed on milk, and wrapped his fingers around a spoon. He chewed and swallowed and padded back to his bedroom. He read a bit of Albert Camus The Mythof Sisyphus, a 120-page essay about the absurdity of human existence. Bachs Brandenburg Concertos spun from his turntable. He stripped to his underwear. He curled into bed. He reached for a canister of pills.

Around 6:00 AM, Drakes heart, overwhelmed by thirty doses of the prescribed tricyclic antidepressant Tryptizol, stopped beating. Six hours later, Drakes mother, Molly, went to check on her son. The first thing I saw was his long, long legs, she remembers.

Two years and nine months earlier, Nick Drake recorded a short, excruciatingly spare album entitled Pink Moon. Pink Moon was preceded by two richly arranged, full-length folk records; all three were released to minimal commercial or critical success. When Drakes death was announced to the public, few who knew him were particularly surprised. Muff Winwood, head of A&R for Drakes record label, Island Records, admitted his lack of shock to biographer Trevor Dann: We saw it coming. We just shrugged our shoulders and thought well, that wasnt unexpected. Drake was twenty-six years old.

It seems somehow fitting that Nick Drakes life ended in his bedroomthe universal haven of privacy and retreatbecause that is where his fans remember and appreciate him best. For us, honoring Nick Drake is a solitary exercise: After everyone else has shuffled off to bed, we uncurl from the covers, tug open the curtains, light cigarettes we wont smoke, and sigh out open windows, squinting at stars and imagining Drake haunting the doorways of Far Leys, sad and wispy, maybe holding a candle, or a half-smoked joint, or a battered brown notebook. We chew our lips, conjuring images of Drake floating through hallways, counting cereal boxes, running his long white fingers over the spines of books, dropping a slab of vinyl onto a turntable. He clutches a cup of tea, drapes himself in a nubby yellow blanket, gapes at the moon. We see him pick up his guitar, wrap his hands around its neck, and play perfect, poignant folksongs.

Thirty-three years have passed since Nick Drakes death, but it is still shamefully easy to romanticize his demiseto sniff and glaze, translating a pedestrian drug overdose into epic, ridiculous verse, twisting his story into one long, tortured poem about art and depression and youth and emptiness. Unfortunately, part of what makes Nick Drake so potent a figure is also what makes his legacy feel so contrived: Drakes (presumed) suicide validated his music much as Kurt Cobains would two decades later, lending his songs credence and weight. Now, when we hear Drake sing about feeling anxious and alone and invisible, we trust his despair. When we listen to

Next page