Also by Amanda Petrusich

Pink Moon

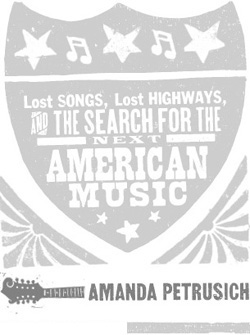

IT STILL MOVES

IT STILL MOVES

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright 2008 by Amanda Petrusich

Photographs copyright 2008 by Amanda Petrusich

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2008

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the editors of Paste magazine and Pitchforkmedia.com, where portions of this book originally appeared in slightly different form.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Petrusich, Amanda.

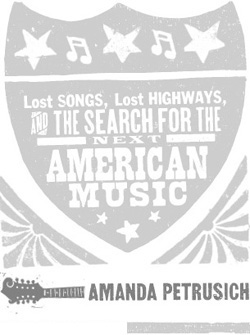

It still moves : lost songs, lost highways, and the search for the next American music / Amanda Petrusich. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-86547-950-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-86547-950-X (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Folk musicUnited StatesHistory and criticism. 2. Country musicHistory and criticism. 3. Blues (Music)History and criticism. 4. Petrusich, AmandaTravelUnited States. 5. United StatesDescription and travelAnecdotes. I. Title.

ML3551 .P47 2008

781.640973dc22

2008002353

Designed by Charlotte Strick

Interior art throughout by Hatch Show Print

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FOR MOM, DAD, ALEX, AND BRET

A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image.

JOAN DIDION

AUTHORS NOTE

Throughout the construction of It Still Moves, I consulted, parsed, quoted, and admired the work of countless published and unpublished authors, but It Still Moves would not have been possible without the research and insight of writers like Ed Cray, Joe Klein, Mark Zwonitzer and Charles Hirshberg, Peter Guralnick, Robert Palmer, Robert Gordon, Colin Escott and Martin Hawkins, Peter Goldsmith, Bill Malone, John Alexander Williams, and too many more to name.

The histories included here are intentionally episodic narratives and in no way represent the full lives or careers of these artists; likewise, there are many essential musicians whose work is not mentioned (or not mentioned extensively). Americana is a broad and varied beastthis is simply my understanding of its story.

IT STILL MOVES

INTRODUCTION

Goodbye, Babylon

Where lies the boundary between meaning and sentiment?...

Between memory and nostalgia? America and Americana?

What is and what was? Does it move?

Donovan Hohn,

A Romance of Rust: Nostalgia,

Progress, and the Meaning of Tools

In October 2003, Dust-to-Digital, a fledgling Atlanta, Georgiabased record label, released a boxed collection of traditional Americana music titled Goodbye, Babylon. Founded in 1999 by a twenty-three-year-old Georgia State University radio DJ, Dust-to-Digital is dedicated to reconciling the past with the present by preserving and digitizing early American songbooks.

Goodbye, Babylon is Dust-to-Digitals flagship release. The box itself is lovingly constructed from cedar and measures about eight inches by eleven inches; the title and a crude drawing of ancient Babylon are etched onto the front in thick black lines. As the top cover of the box slides forward, its insides are slowly revealed in a shower of soft splinters. Two of the four compartments are packed with unprocessed cotton flowers, lumpy white puffs riddled with bits of dirt and seeds. One houses a short stack of six CDs, each disc enveloped in a thick brown sleeve. The last holds a big, tightly bound booklet containing liner notes written by the renowned musicologist Dick Spottswood.

Each of the six discs included in the Goodbye, Babylon box pivots around a central theme: the first disc, which functions as an introduction to the entire set, is dedicated to the exploration of death, joy, salvation, and the apocalypse. Appropriately, the title track, Reverend T. T. Rose and Singers Goodbye, Babylon, cites Revelation 14:8 (which roars: And there followed another angel, saying, Babylon is fallen, is fallen, that great city, because she made all nations drink of the wine of the wrath of her fornication), and the songs lyrics (I told you once, told you twice / You cant go to Heaven by rolling dice!) playfully mimic the Bibles staid counsel.

That primal oppositionsin versus pietyis slathered all over the Goodbye, Babylon box and has invaded nearly every other bit of popular American music recorded since. It is, in many ways, the most central American dilemma: We are an ostensibly devout countryone of the most religious in the worldthat is also preoccupied with temptation. We are a nation of hell-fearers and heaven-hopers who still like to have a good time, and that tension seeps into nearly every cultural artifact we produce. From Goodbye, Babylon on, Americana music is dedicated to exploring that divide, to poking at and magnifying all of the different things that make us American.

Recorded in Grafton, Wisconsin, in April 1930, the Reverend T. T. Rose and Singers version of Goodbye, Babylon is all spirit and very little sound: theres tape hiss and piano and wild, throaty warbles, but ultimately Goodbye, Babylon is, like all Americana music, the kind of thing that lives and thrives in the dark, gooey pit of your stomachnot in your ears.

Its half past midnight when I slip the first disc into my stereo. A taut piano melody rises stoically, pushing hard through a heavy curtain of tape hiss. Jerky but determined, the piano waddles on, commanding everyone within earshot to engage in some variation of sharp, heel-toe jigging. I dance, shimmying backward, ponytail swinging. A man starts shouting; his voice is weird and unwieldy, overemphatic, barky. A pack of women chime in emphatically, finishing his thoughts: Goooodbye! he yaps. Babylon! they holler back.

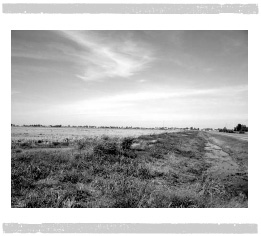

Goodbye, Babylon is so stoic an object, so unwavering and certain, its hard to imagine it was constructed around an idea as nebulous and tentative as Americana. Collective notions of Americana tend to be both knee-jerk and bizarre: as an umbrella term, Americana is convoluted and sloppy, so overloaded with vague connotations and heavy-handed nostalgia that its been rendered almost meaningless outside the faux-log walls of Cracker Barrel gift shops. Consequently, its difficult to talk about without feeling like youre narrating the aw-shucks contents of a Norman Rockwell painting. The word invariably provokes a barrage of clichd images (think waving fields of golden wheat, wind-rippled flags, and steaming apple pie), quasi symbols that made the grand, unflattering leap from emblematic to silly a long time ago. What does Americana look like? Is it a John Deere alarm clock? A wooden yo-yo? A peppermint stick? A tin of Virginia peanuts? What does it sound like? Does it move?