Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

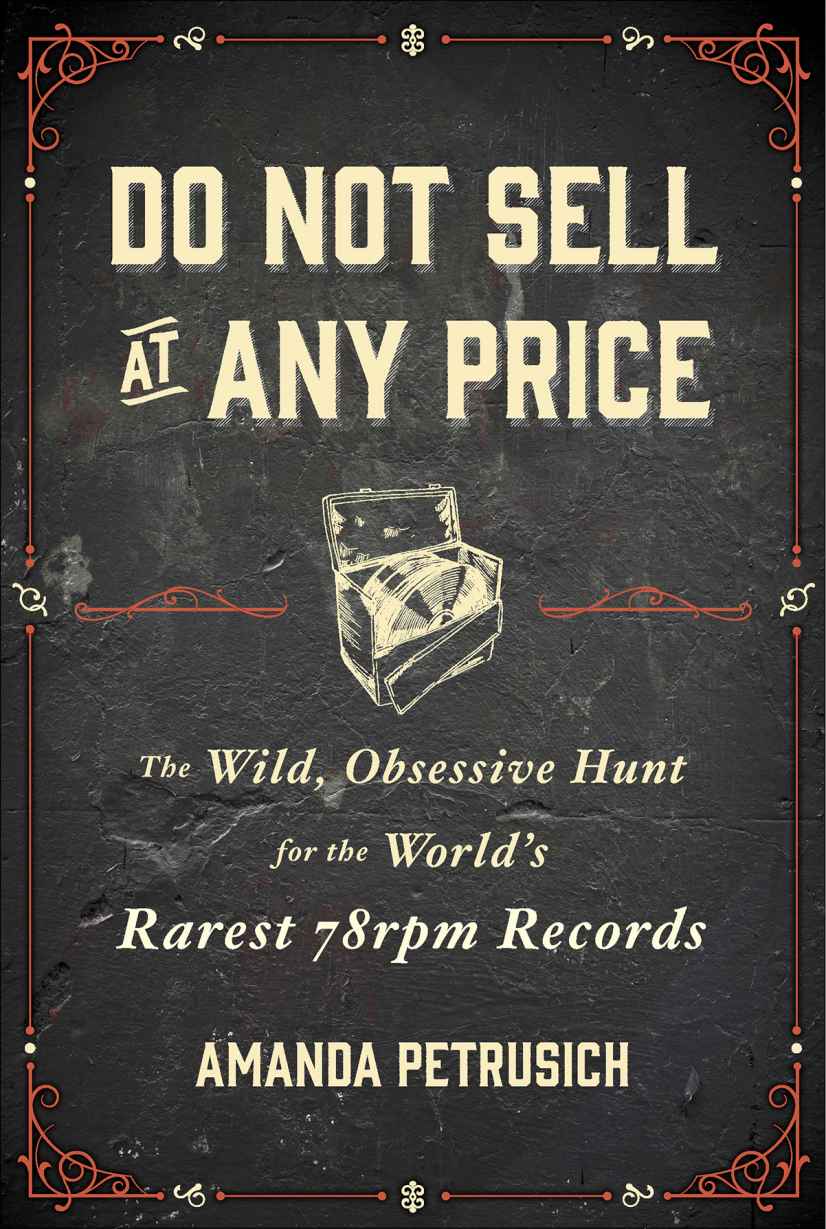

For my parents, John and Linda Petrusich

Listening to music, I always have exactly the same feeling: somethings missing. Never will I learn the cause of this gentle sadness, never will I wish to investigate it. Ive no desire to know what it is. Ive no desire to know everything.

Robert Walser (translated by Susan Bernofsky), Masquerade and Other Stories

/ / Prologue / /

An Air of Impoverishment and Depleted Humanity

Music Criticism, the Culture of 78 rpm Record Collecting, Jean Baudrillard, Mouth Breathing, the Lure of Objects

I was a pretty good kid with rebellious aspirations. I spent most of my adolescence listening to punk-rock bands on my plastic Sports Walkman and, like many young music fans, I self-identified via my record collection (for me, a sticker-coated trunk packed with cassettes). Because I came of age during the pinnacle of grunge, I further expressed that identity via Doc Martens, Manic Panic, and flannel shirts I pilfered from my fathers closet. As I grew older, my communion with music became more complex and less visceral, but it was still my primary method of self-expression: I was what I heard, always, and I eventually parlayed those delusions into something resembling a career as a music critic.

The crowning perk of professional music criticismthe only perk, maybe; its not a particularly glamorous gigis that your mailbox is routinely crammed with dozens of padded envelopes containing CD copies of upcoming releases, shipped en masse by labels, publicists, or the artists themselves. That tottering stack of plastic can feel as much like an albatross as it does an opportunity, and practically speaking, the volume of material (at its height, Id say I was unwrapping between sixty and seventy new CDs each week) is a curious thing to manage. I have to goad a pal into collecting my mail every time I go out of towneven just for a few nights, lest a mound of manila alert the entire neighborhood to my absenceand since my apartment cant possibly accommodate all the CDs that come through, Im routinely developing new ways of disposing of albums that I dont like or cant write about or never found the time to hear. Getting free records used to at least feel like something of a coup. These days, music fans with no critical aspirations can instantlyand freelyexperience the same kind of oversaturation. If you have a computer and a modicum of Web-browsing savvy, its not difficult to acquire leaked versions of new records months or weeks before their street dates. An unreleased song or album can be detected, acquired, and judged in the time it takes to prepare and eat a grilled cheese sandwich.

Obviously, free promotional material is an absurd thing for anyone to grumble about, but at some point, the process did begin to skew my perception of what music looked like and how it should be valued. Its reductive to suggest that the availability of free or nearly free musicand the concurrent switch, for most of the population, from music as object to music as codehas inexorably altered our relationship with sound, and I dont actually believe that the emotional circuitry that allows us to love and require a bit of music is dependent on what it feels like in our hands. But I do think that the ways in which we attain art at least partially dictate the ways in which we ultimately allow ourselves to own it.

For me, the modern marketing cycle and the endless gifts of the Web had begun to feel toxic, and not necessarily because I was nostalgic for CDs, then the primary musical medium sold in my lifetime, or because I thought the music industry was a beacon of efficiency before. It was because, for the first time in my entire life, I didnt care about any of it.

By all accounts, the first decade of the twenty-first century was a disconcerting time to be a music fan. By 2005, the ritual of consumption had been almost entirely annihilated: acquiring and listening to music was, suddenly, a solitary exercise that involved untangling lots of little white cords. Like many people, I missed browsing record stores, buying albums based exclusively on cover art, hobnobbing with bespectacled clerks in Joy Division T-shirts. I could still do those things, but suddenly it felt like a pose: Here I am! Buying records!

Moreover, I missed pining for things. I missed the ecstasy of acquisition. (In 1993, it took me seven weeks to sniff out a copy of Dinosaur Jr.s Where You Been , and I spent the next seven memorizing every last crooked riff.) I missed making literal investments in music, of funneling all the time and cash and heart I could manage into the chase. I had free CDs and illegally attained MP3s and lawfully purchased LPs, but unless I was being paid to professionally render my opinion, I listened to everything for three or seven or nine minutes and moved on. I was overwhelmed and underinvested. Some days, music itself seemed like a nasty postmodern experiment in which public discussion eclipsed everything else, and art was measured only by the amount of chatter it incited. Writing and publishing felt futile, like tossing a meticulously prepared pork chop to a bulldog, then watching him devour it, throw it up, and start eating something else.

It was around thenthe fall of 2007, the apex of my disillusionmentthat I met John Heneghan. I was researching a story about the commercial resurgence of vinyl records for Spin , and Id been pestering Mike Lupica, then a DJ and the director of the WFMU Record Fair, for the names of a few prominent collectors who might be willing to speakforcefully, and on the recordabout the relative lowliness of digital music. I was looking for a violent retaliation. Lupica slipped me Heneghans phone number with a caveat: These 78 guys are on another level .

While vinyl has enjoyed a welcome and precipitous renaissance in the last decade, 78 rpm recordsthe thick, ten-inch, two-song shellac discs developed around the turn of the twentieth century, and the earliest iteration of a record as we think of it todayare still considered odd and archaic. Because there is so little popular interest in the format, even hunting down a turntable capable of playing one is a challenge. The grooves in a 78 can be two to five times wider than those in a modern LP, so a different kind of stylus is required in addition to a motor that spins at 78 revolutions per minute, rather than the standard 331/3 or 45 rpm. Even the most ardent vinyl fans are likely to push a stack of 78s aside rather than obtain all the equipment necessary to get one to play. Its not a medium that invites dabbling.

I already knew that 78 fanatics were part of an intense, competitive, and insular subculture with its own rules and economicsan oddball fraternity of men (and they are almost always men) obsessed with an outmoded technology and the aural rewards it could offer them. Because 78s are remarkably fragile and were sometimes produced in very limited quantities, theyre a finite resource, and the amount of time and effort required to find the coveted ones is astonishing. The maniacal pursuit of rare shellac seemed like an epic treasure hunt, a quest storyan elaborate, multipronged search for a prize that may or may not even exist.