To the girl who wont sleep until shes had a story.

Contents

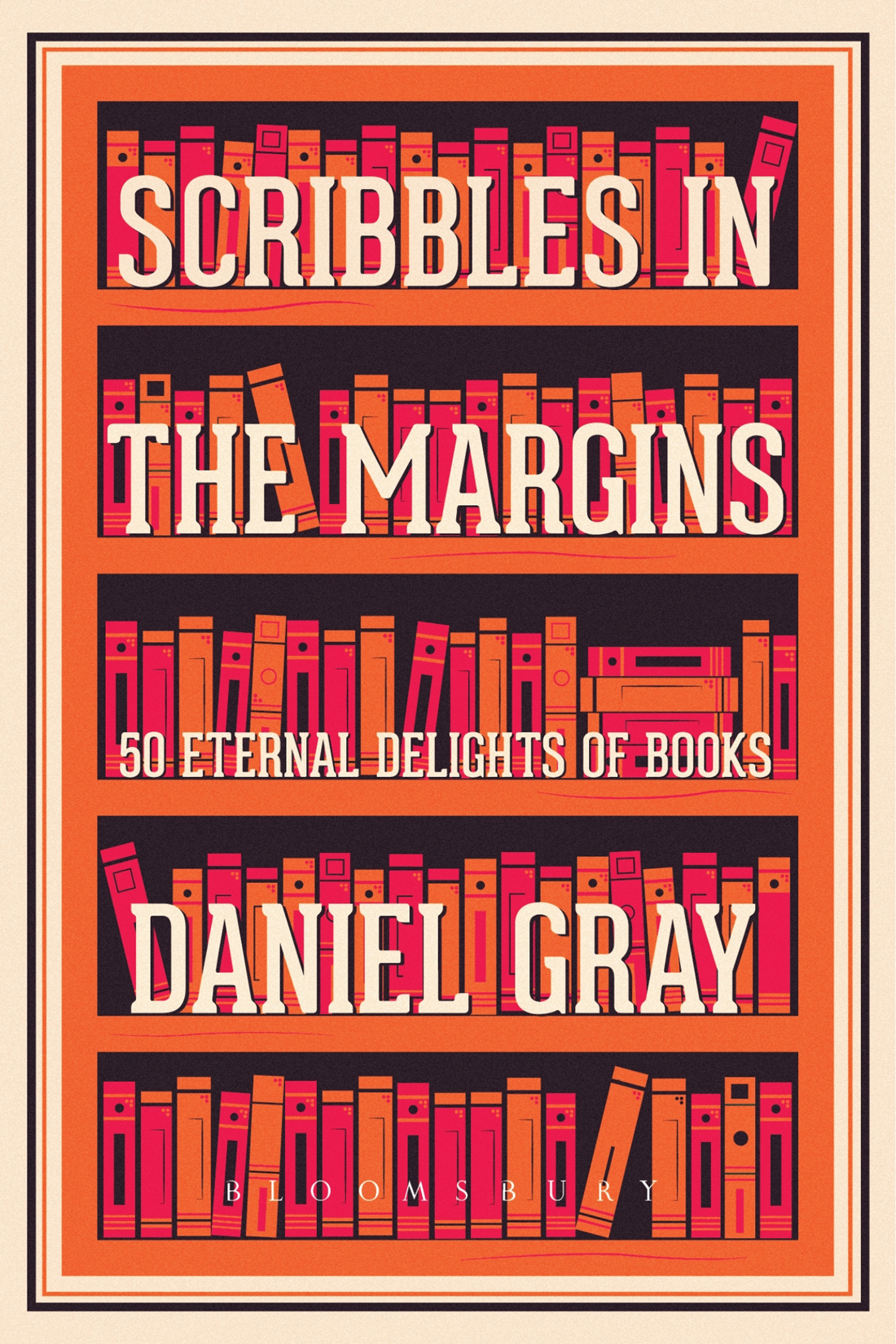

It is obvious and easy for an author to proclaim the many charms of books. Here, though, I am writing as a reader. This particular book is an attempt to fondly weigh up what makes a book so much more than paper and ink, how reading is so much more than a hobby, a way of passing time or a learning process. It is a celebration of the trivia that so many of us revel in, even if we dont quite realise it; an observational gallivant among impromptu bookmarks, the scents of bookshops and reading in bed.

This Delights book was inspired by the chance find, in a pub, of another. In J. B. Priestleys Delight , the author, a self-confessed Grumbler, toasts all that is good in the world. He is writing his way out of despondency with grim and grey post-war Britain. In short essays, we share his delight with Shopping in small places, Frightening civil servants, the Sound of a football, Sunday papers in the country, Smoking in a hot bath and 109 other topics.

Priestley sought to remind his readers that there remained simple pleasures in life, no matter how dark our surroundings may seem. Now, in a cynical, jaded world of distressing news bulletins and online trolls, a world monstrously faster and angrier than Priestleys, this message is once more required. For so many of us, such sweet solace is to be found nestled among pages.

These declarations of love are about the book as a physical, almost living, object, and the rituals that surround it. They demonstrate what books and reading mean to us as individuals, and the cherished part they play in our lives from the vivid greens and purples of childhood stories to the dusty comfort novels we turn to in times of adult flux. Books are an escape door open to all people, and this one is a cosy reminder of how and why.

The long-predicted slow death of the book now seems unlikely, rendering this a good time for us to rejoice in the many and sometimes odd little ways in which the book makes us happy. Further, the place of books needs a cheerful salute, which I hope this volume is; books remain at the fulcrum of society, education and culture. They withstand and are sometimes at the forefront of technological change ebooks are an ingenious invention and offer many joys of their own and social trends. They still rescue many a difficult Christmas present conundrum.

Books are more attainable, and therefore democratic, than ever before. Reflecting this, these delights are, I hope, universal indulgences that are felt by the prisoner and the priest, the library-addict and the owner of a personal library. Read them, think about your own, and then move on to another book...

To my Dear Husband. August 16th, 1936. From Betty with love, Xmas 49. To Sarah, keep this with you as you go. Love, Mum and Ron x. Each of these sits snug in the top left-hand corner of an inside cover. It is almost as if the words know they shouldnt be there and are attempting to creep from the page. The handwriting is always ornately joined Husband like an unfurled and manipulated streamer from a party popper; Xmas like a careful Red Arrow vapour trail and the ink is charcoal black or early-evening blue.

The messages carried are celebratory and loving, though often in the simple and restrained language of their age. Sometimes, you sense that pen and ink liberated a book-giver not prone to spontaneous declarations of affection to go wild: To darling Thomas, happy birthday, Father. There are in-jokes, too, knowing references we will never understand, and the vaguest silhouettes of lives.

Such great unknowns of book dedications are a significant part of their charm. We are transported backwards to when this book was first chosen and given, a story within the story, but this time we will never know the ending. Did Thomas enjoy the book? Did the Dear Husband even read his? Did Sarah carry hers, and to where? As so many are dated like vital contracts, we can smother these notes in their historic periods anything written to a son between 1900 and 1914 is especially poignant but still we are only guessing at what happened next. Did the receivers like the book, perhaps lend it to friends? How many times have these words been loved before? Was it not really the title sought after, unwrapped impatiently on Christmas Day and gladness feigned? How did it end up in the second-hand shop, or in the warehouse of the online used book retailer? Had it been cherished until death and house clearance? Or passed around, through the ages, a restless minstrel yet to find home?

These paper time-machines shroud us in the comforting thought that a book has a life, and we are now a part of it. They add an extra layer of pleasure to buying an old book, and create a timeless connection between you and a long-gone reader. The two of you now share a never-to-be-revealed secret. Your lives may have been lived in very different worlds, but they are united by the exact same ink and characters.

The next time you give a book, take a moment to write a few brief words to the gifts recipient. For you are also reaching out a hand to someone who hasnt even been born yet.

As a child, the houses I frequented had very few books on display. Most, including my home, had one or two shelves worth, usually part of a dining-room cabinet and behind glass, as if they were to be seen and not read. Scattered in no particular order would be an abridged encyclopaedia, a bible, a dictionary, a couple of Jilly Cooper novels, some hardback photobooks about war, a set of unread plainly-bound volumes received as a gift, titles about diets and canals pertaining to midlife crises and short-lived hobbies, a tired atlas and a large annual tying in with a BBC television series.

The people who owned these shelves my parents and my friends parents were born just after World War Two. When they read, books were not bought, but borrowed. Libraries were necessary and useful, whereas living-rooms were for porcelain ornaments and the telly, and not showing off. Perhaps it is why in adulthood I am fixated with bounteous shelves, and indeed with building up my own collection we never had bookshelves, now we must have two rooms containing them. They are my pampered generations version of indoor toilets. Or, perhaps I am just nosey.

I know that I am not alone, that there are, right now, people scanning others bookshelves and getting to know their owners in a way conversation would not allow. These shelves are someones biography that, try as you might to avoid it, reveal covers by which they can be judged. This isnt entirely unfair or sinister: what better way to decide if a new lover is worth wasting time on, or to find something in common with your hosts when forced into a social occasion by your more affable partner? It is also possible that those hosts want you to look at their shelves a book collection can be an ostentatious display of intelligence and worldliness.

Arrival in a house or a flat kindles a desire to secure time alone with the bookshelves. The offer of a drink, preferably a slightly complicated one, is accepted, a distraction for your ferreting. Should a host be cooking, all is golden and hours are plenty. By the time he or she is washing up, a character profile has been shaped.

Either way, there will be a rushed early scan of all shelves as you excitedly inhale the books facing you like a cat in a fish and chip shop, and pull loose two or three titles in quick succession. You might find yourself flooded with book envy, or sighing longingly at an alphabetically-organised collection of near perfection or a vast swathe of orange Penguin Classics. If there are at least half-a-dozen volumes that you too own, the omens for friendship or more are good.