To the girl whose blue eyes are lit by green

Contents

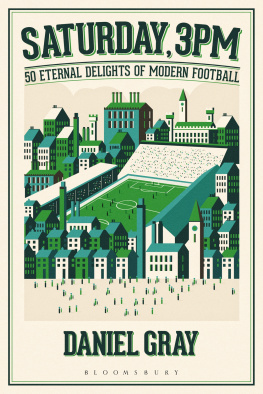

There remain excesses and irritants that make us question our slavish adoration of football. That much is unchanged since I wrote a first book of 50 delights in 2016, Saturday, 3pm . In particular, the clumsy introduction of VAR has lately summoned wrath from English Premier League fans. As was the case when I began that book, it would still be easier to write a work of 50 rants than one of 50 romantic salutes. However, this game still transfixes me. It chokes me with glee. It starts my days and ends my sentences. I find refuge in football, and I want to talk about it, and to share what I feel.

The reaction to Saturday, 3pm demonstrated that I was not alone in the particulars of my captivation. Chapter entries made sense, resonated and elicited nods of agreement. Even topics I had worried were personal to my, well, strange thoughts proved engaging; four years on, at least once a month, via Twitter or email someone sends me a photograph of a football ground taken from a train. In that time period, others sent me their own delights, a true thrill for a writer. Encouragingly, many offered them up for a second volume, and asked if such a thing might one day be published.

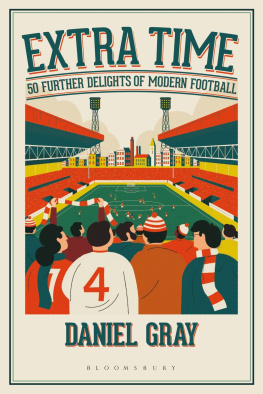

There had not been enough room in Saturday, 3pm for every delight that I had written on my ever-sprouting list. I put it to one side, but found myself frequently adding to it. In fact, cataloguing these one-line pleasures of football has become something of an addiction. As it grew, and as I remained besotted by the details of football, Extra Time became inevitable.

This book, then, is a sequel, but the source material is every bit as rich, my love for the sport, if anything, greater than ever. In style and format, it is a continuation of Saturday, 3pm , once more inspired by J. B. Priestley and his wonderful 1949 work, Delight . If you read Saturday, 3pm , then thank you and I hope this prolongs the conversation. If you didnt, worry not: there is no plot and nothing complicated happening here, just a celebration of football, its culture, customs, habits and peculiarities. These 50 further entries are merely more love letters to add to the drawer. I hope that each is like a short story, but that everything comes together to remind you, the supporter, why you bother. Because, as this book attempts to show, even on the rainiest Saturday there is something to delight in.

My other hope is that Extra Time will help renew its readers love of football. It will grow faith in the shared experiences of being a follower of the game a comforting feeling that no supporter is alone in his or her eccentricities. This book strives to demonstrate that, in a world coming apart at the seams, our sport and its technicolour minutiae offer an escape needed now more than ever. These 50 nuggets of pleasure are a sweet medicine in the face of disillusionment with modern football, VAR and all, reminders of why we care and justifications for our devotion. It is time to start counting the love again.

He sits up there, at the centre of the main stand, an alert seagull on a chimney pot. His hands clutch a microphone as if in prayer. On his jacket breast is the logo of the local radio station he talks for. He starts to feel a chill in late August, and it doesnt leave him until the following May.

This is a stoic role, and one pitched at the extreme of broadcasting, a gulag with endless tea in Styrofoam cups. To the absent supporter, though, his words are a life-support machine. He delivers matchday to thousands of ears unable to be there, in doing so remotely adjusting heartbeats. For a few hours his voice becomes that of an internal deity, creating worlds and actions, shaping happiness or despair.

The local radio commentator grows to be the voice of a team, and even its town. His words, accent, tone, cadence come to represent events. This happens in real time, as listening supporters follow every pass in their mind, and retrospectively if you support a club thats hardly saturated in media attention, then it is his voice that soundtracks rare highs and dire lows when you play them back in your mind.

In your area that voice is as familiar as pedestrian-crossing beeps, and yet in other places it is unknown. A sound that immediately transports you elsewhere and blows thunderous goosebumps of recall is mute even in the county next door. Only when reference is made to colleagues at the opposition teams attached radio station does it seem possible that others could feel about their commentator as you do about yours.

He is there for home games, of course, welcomed in and nodded through from security guard to steward. You need him for missed fixtures, and for the casual and partial fans who rarely venture to the ground, he is the match. It is away games, however, that elevate his importance.

Each week, he tootles across the motorway network in a busily branded radio station car. It is too small for him, and certainly too small for the summariser he chauffeurs, usually a retired ex-player from your side who can talk uselessly on demand. On air, both are unapologetically, splendidly biased, a fine thing in a world of sensitivities, eggshells and protocols. They share and proclaim your affinity and your blindness, and their moods swing to the same pendulum as yours. This is the commentary of we, our and us.

The local commentator pulls you from the living room and drops you on the terrace. Vivid sketches from faraway towns fix sharp and clear behind your eyes. When you hear your own supporters singing, from some hidden corner belting a hymn you know well, you are almost there with them. Were it possible to plunge a hand into the radio, grab some of the atmosphere and splash it on your face, you would.

Afterwards, home or away there are familiar, seldom-fractious interviews with managers and players, and perhaps a phone-in. Then, the local commentator disappears to do whatever else it is he does, his words still echoing through unseen ears.

Some lotto sellers are one-trick street performers, enticing passing fans with feverish cries and wild promises of fortune. Some stand motionless hoping buyers will find them, like meek prom debutantes waiting to be asked for a dance. Whether bellower or murmurer, the half-time draw vendor is an incidental and yet essential pillar of matchday. So much of going to football is about routine and certainty. Outside every ground, there are constant elements with their own local variety, from mouthy scarf traders to weathered fanzine editors. Lotto sellers and the sweepstake chits they offer are another species in our wildflower meadows.

Supporters often buy from the same seller, deemed lucky despite vending a seven-year run without even a third prize win. Tickets always cost 1, and any deviation would cause confusion and represent the early signs of a society in meltdown. The 1 product never has expansion room a reasonable rise to 1.50 would mean fiddly change, a practical rise to 2 would mean outrage. This is gambling with genuine and welcome limits. There has never been a story of hellish addiction to football club lottos. Anyone attempting to buy more than, say, five tickets would be met with sarcastic cries of Who do you think you are? Rockefeller?

There is pleasure and ritual, too, in the physical ticket. Its very existence is something to treasure: in the print-at-home and barcode era, here is a tactile item that can be kept, something collectible for the hoarding football supporter. Of course, a more likely ending for it is in a dozen pieces, torn asunder when its numbers fail and then scattered into the air, a theatrical act of momentary dejection. Its fragments rain on the row in front, a dream in tatters. Up until then, there was joy in hope and indeed in the ticket itself, with its traditional, no-nonsense design, its capitalised promises and its lucky number in Courier font.