To the girl I lift when we score.

Contents

For taking me in the first place, Dad; for always indulging and supporting me, Mum; for putting up with losing-weekend moods, Marisa; for making football sparkle anew, Kaitlyn. Heartfelt thanks to my agent David Luxton, my publisher Charlotte Croft, my editors Holly Jarrald and Sarah Connelly, and my copy-editor Karen Rigden.

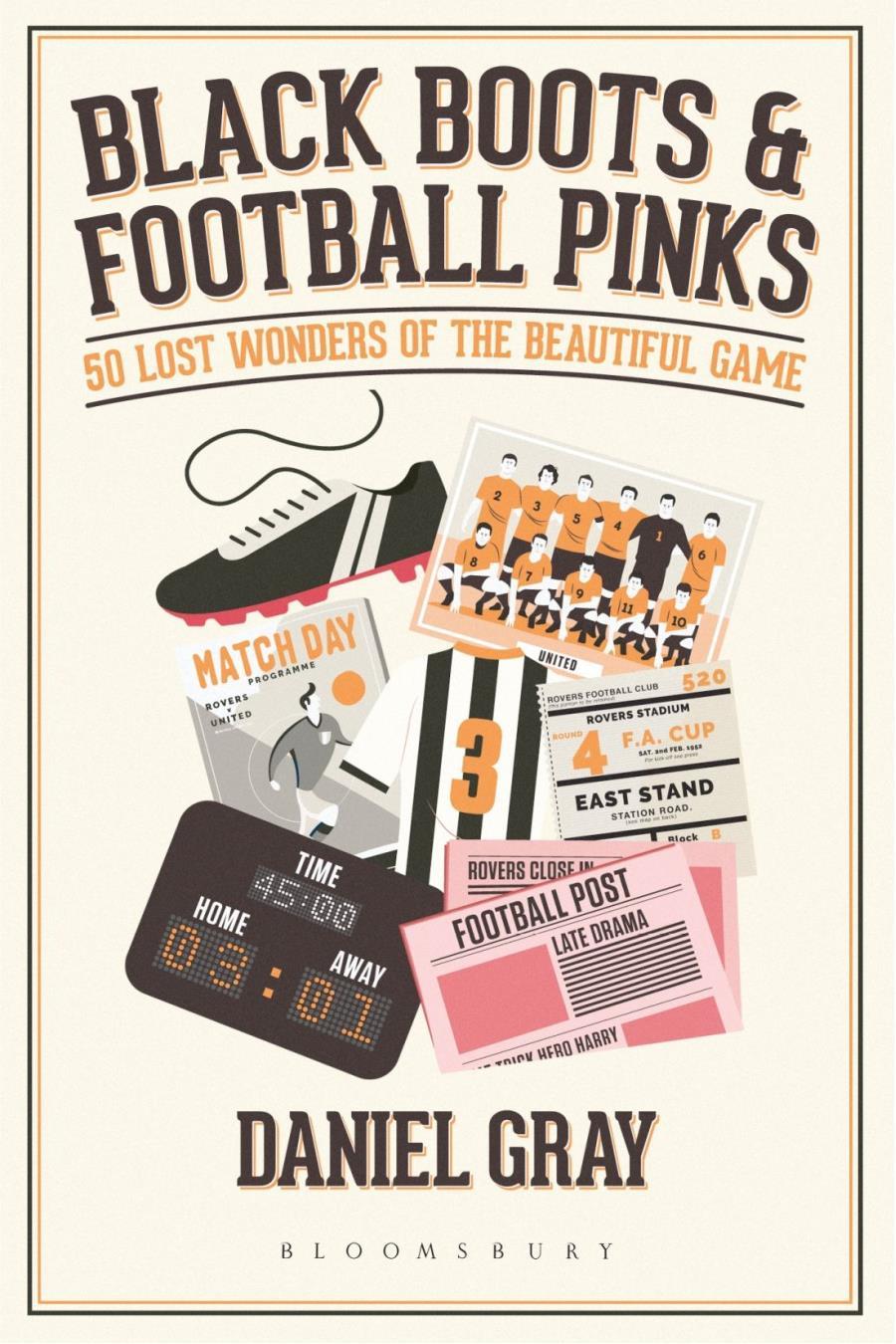

Thirty years ago, I went to a football match for the first time. The environment of those early supporting days shaped my obsession. Here was a sport closer to its Victorian rise than its televised future.

Over these three decades, much of what I knew has faded away or been replaced. It has been both a fascinating and a heartbreaking time to be in love with football. I am marked by a desire to record what is gone, the consequence of which is this book. I wish to preserve in words the relics of our identity.

My supporting life has straddled two worlds old and new football. I am guilty of glorifying the former and tutting at the latter. Right or wrong, I know I am not alone. This book is for those people who look at a picture of, say, Maine Road and sigh with longing. It is for people who miss being told the hometown of a referee, and pine for miserable turnstile operators or pixelated scoreboards. I hope that it will make some of these things feel within touching distance, even if that can never again be so.

I have written it, too, as my own subjective record for people who dont miss those days, or werent there. Whatever your outlook, this is an account of what some of us saw before all memory of it fades. It is an attempt to sketch a ghost before it leaves the room. In some ways it is written from the future. Not every wonder is gone from everywhere not every last turnstile operator has yet been replaced by a scanner but it soon will be. That is the course set for the game, unless authorities and financiers start to value preservation and authenticity as many supporters do.

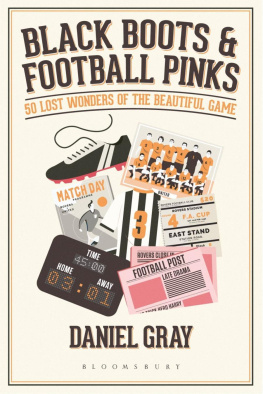

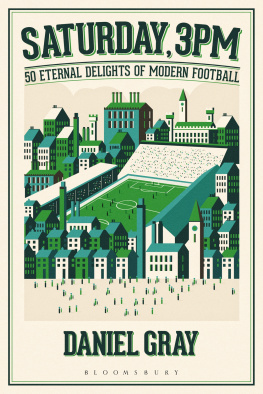

Each piece that follows is unashamedly nostalgic and sentimental. Such qualities are often scorned, as if to be pro-nostalgia is to be anti-progress and against all change. Yet there is nothing regressive or conservative about looking back when it brings solace and joy or provides an escape from the everyday. There may even be ideas here worth resuscitating. I saw the unifying powers of recall with my earlier book, Saturday, 3pm , whose more nostalgic chapters often provoked a warm, amused and even buoyant reaction.

There is a danger here, of course, of revisionism. December 1988 in Middlesbrough was four months before April 1989 in Sheffield. I recognise that old football was not some sprightly Maytime there are no entries on the thankfully departed, from fences to casuals. Where old scents of football are remembered, they are of the Bovril rather than bodily type.

I have tried not to rant or moan, though on occasion that proved impossible; pointing out what is becomes necessary to contextualise what was . It is important, too, to recognise what corporate money and globalisation have taken from the game. Millions of us feel alienated, feel the game has lost much of its personality, and that so much character has been thrown away.

Here then is a last goodbye, a celebration of what we had. There is, as I hope I have shown before, much to delight in about the modern game. This glimpse backwards, though, seeks to offer cosy refuge from a boisterous game and world. Come back with me.

There can never be too much football. For some of us, it is there to block out things we struggle to understand. The longer we can keep the curtains drawn, the better. League games, domestic cup games, European games, summer tournaments. Even, in desperation, pre-season friendlies. Play on, give us excess of it. If anything, there should be more of it, cheering and speeding up our weekdays too imagine how much faster an afternoon would shunt along if there were scores to check up on or radio commentaries. We do not have to be there; it is just reassuring to know that football is going on.

When penalty shoot-outs toppled the limitless cup replay, we lost one such caterer to our excessive needs. An eternal fountain was stemmed, sealed and left to decay. No more winter nights of two teams inseparable, clutched together in a rigid deadlock through a dozen kick-offs and six equalising goals. Such an impromptu string of games was the nearest football got to a Test match series. On day one, a scoreless draw meaning a Wednesday night 22, and that after extra-time. Then, another 120-minute impasse, and a further replay.

When the stand-off was at last settled by one teams slender victory, it seemed both a shock and faintly bad-mannered. The players were now familiar with one another. There was mutual respect among persistent equals perhaps friendships across the halfway line bloomed. Supporters knew opposition players as well as they knew their own. They were on nodding terms with away-end stewards. Both managers had run out of tactical insight or game plans, and relied only on prising yet more effort from their charges and the hope of a fluke goal. Interminable replays bred a grudging form of solidarity.

There was much to admire in just how thoroughly equal the two teams were. In its own way, the repetitious cup tie was like watching two boxing greats jousting for hours on end. Again and again, these two teams cancelled one another out. Each attacking manoeuvre was met by a mirror defensive reaction. Everything was null and void, with each occasional goal struck dead by a leveller. It was either the height of sporting contest, or a symptom of goal-scoring ineptitude. Probably both.

By the third or fourth game, replay footballers were clobbered by a seismic breed of tiredness. Everything hurt, inside and out. On pitches of clumpy grass and sinewy mud, they had run pointless marathons with no finish line. Then, after seven or nine hours of slog, a saggy, weary, clumsy, drooping, floppy goal would end it all. Two hitherto disparate clubs now had an infamous period in common, a holiday romance beneath floodlights.

On that divine and hopeful strut to the match, there were the sounds you passed and those you went towards. Drifting by the mouthy callers selling programmes, lotto tickets and burgers, and the soloists and choristers intoxicated by ale and nerves singing their hymns in an unknown key, your ears guided you ever forwards to a fixed target. The football ground was speaking to you. Its muffled din of announcements and tinny records summoned and beckoned.

Walking these streets that on Saturdays were surely yours, it could be heard beneath everything. It was an entirely pleasant form of tinnitus, a comforting sound lining your ear. It was faint background noise, as pleasant as birdsong or a milkmans whistling. It intruded upon nothing, and seemed barely louder inside the ground than outside. The announcers voice was smothered. Though the player names read out in the line-ups were familiar, it took effort and strain to decipher them, as if someone was whispering at you through a gas mask. There may then have been run-out music, but it was easily overcome by throttling applause and furtive chants. Then the supporters were left to it. They made their own noise.

There was no juggernaut sound system vibrating the sky, no pre-match bombast. Atmosphere was spontaneous, impulsive. There was no hint of a choreographed experience or spectacle , no ear-smashing dance anthems raging right up until the referees whistle, no cacophonous announcer telling you to make some noise. Merely, a few thousand people singing and cajoling in those bullish and utopian minutes prior to kick-off.