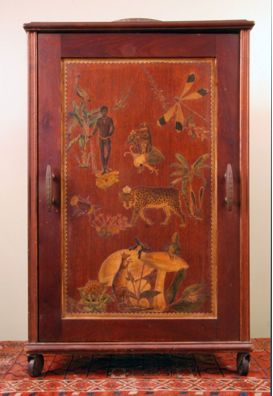

In the corner of our dining room, there's an old half-round cabinet on wheels. It has a handsomely decorated front-panel that swings around on a lazy susan to reveal a collection of whiskey glasses and decanters on the other side. It's what's sometimes called a hide-a-bar, though we use it now mainly as a place to charge our cellphones. We keep it prominently displayed because we like it. But it also oddly embodies the split life of my mother-in-law, from whom we inherited it. And it has lately shaped the course of my own life both as a writer and a son-in-law.

For the first 12 years that I knew her, my wifes mother Janice, a slender, insecure woman, seemingly cowed by life, was an alcoholic. She drank Scotch from late morning onward, like her father before her. Janice allowed, when I started dating her daughter, that she wasnt too sure about me, probably with good reason. (I was a young writer with an interest in the natural world, semi-employed, somewhat surly, and a Democrat.) But I was pretty sure about her, and not in a good way.

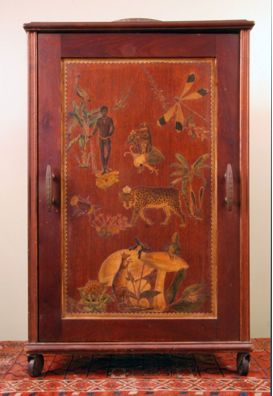

Janice Braeder exhibiting her decoupage.

She was from a generation of suburban women whose fathers and husbands did not allow them to have jobs. Instead, she practiced decoupage, a craft or art form in which she meticulously cut out images and then re-arranged them as ornamentation on mirrors, lamps, and furniture, for sale through gift shops and decorators. For her raw material, she cut up beautiful old books of illustrated natural history. I gasped the first time I saw it. I probably also used some indiscreet word like vandalism.

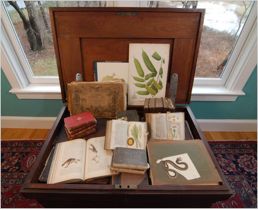

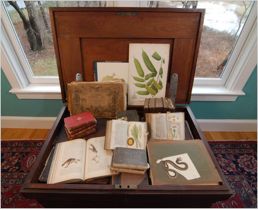

Some of the books Janice Braeder used for her decoupage. (Roger U. Williams)

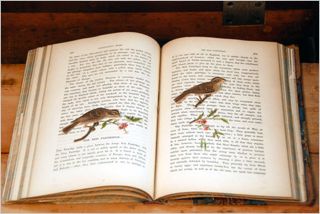

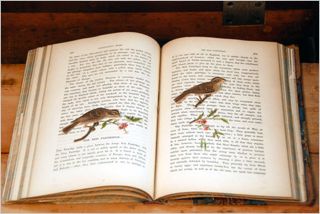

In the 18th and 19th centuries, such books were a crucial tool of the great age of species discovery. Naturalists then did not understand how to preserve specimens. So they often became artists out of necessity, and sometimes described a new species based only on a careful drawing. Artists, caught up in that eras euphoria about new discoveries, also became naturalists. George Stubbs, for instance, once threw on his coat at 10 p.m. and rushed out to bid on a menagerie tiger that had just died. He also spent many long days trying to capture the essence of some astonishing new species as the specimen was rotting and stinking before his eyes. Hand-colored engravings became the means by which the outside world first came to know such marvels of the day as the kangaroo and the platypus. Particularly in Britain, lavishly illustrated books of butterflies and birds even A Popular History of British Zoophytes, or Corallines became perennial bestsellers.

The Silver-blue Butterfly by Frederick Nodder

And some of them had survived to be carefully disassembled by Janices decoupage scissors. As a writer, I was frequently away in rain forests or savannas, collecting tarantulas or tracking leopards. But when I came home, those old images of discovery were all around our house, rearranged in beautiful and sometimes disorienting patterns on mirrors, candlesticks, and other objects she had given us. On the front of the hide-a-bar, for instance, a kangaroo stands with its forepaws up, as if in prayer, before a huge Alice in Wonderland toadstool. A rat-like marsupial sits upright on a tuber, as if yearning for a hookah, while a litter of youngsters squabble higgledy-piggledy around her pouch. A hummingbird wings down to whisper in the ear of a black man who stands naked, with a sheaf of spears in one hand.

Decoupage candles (Roger U. Willams)In time, Janice came to regret cutting up old books and prints and switched to color photocopies instead. (One day she also stopped drinking, without a word, and stayed sober for the rest of her life.) But she still had boxes of ruined books, and when she died, they ended up in our attic. A few years ago, I started bringing them down to read in bed, and found them strangely atmospheric and compelling. It wasnt just the illustrations, with the peekaboo holes where species had fallen victim to decoupage. I also liked the language. The nature of classification is to pin things down as exactly as possible, so it was precise and technicaland yet with a kind of poetry: Shell small, thin, oval, turgid, inequilateral, not gaping. Valves concentrically wrinkled and beautifully striated.

I also got caught up in the adventures of the people doing the discovering, like the British ornithologist in India who got tossed twice by bison, was trampled by a rhinoceros, lost his left arm by jamming it down the throat of a charging leopard, but remained, thank god, a good tennis player, as his obituary noted when he eventually died an old man, in bed.

Images of animals that the authors mother-in-law stored in books. (Roger U. Williams)Sometimes as I was browsing through a book, one of the animal images Janice had cut out, but never used in her art, came slipping out from between the pages: A snake trying to slither back into the living world, an elephant landing weightlessly on my chest, a stag beetle set free, with all its antennae segments and jaw parts and even its claws perfectly intact. It was like living with an ancestors trophy collection, but with a vestigial knack for meandering. And gradually it dawned on me that my mother-in-law had been mesmerized all along by the same thing that mesmerized me the natural world in all its strangeness and wonder.

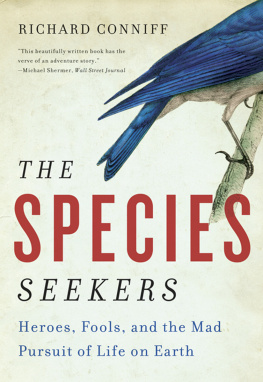

In time, I wrote a book about the wild epoch of discovery that her collection and her decoupage opened up to me, and when The Species Seekers came out recently, it was illustrated in part with some of Janices stray animals, a son-in-laws way of saying, too late, both Thank you and Im sorry.

Dying for Discovery

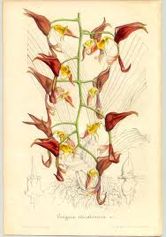

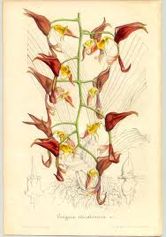

Gongora odoratissima

Almost 20 years ago now, in western Ecuador, I traveled with a team of extraordinary biologists studying a remnant of forest as it was being hacked down around us. Al Gentry, a gangling figure in a grimy T-shirt and jeans frayed from chronic tree climbing, was a botanist whose strategy toward all hazards was to pretend that they didnt exist. At one point, a tree came crashing down beside him after he lost his footing on a slope. Still on his back, he reached out for an orchid growing on the trunk and said, Oh, thats Gongora, as casually as if he had just spotted an old friend on a city street.

The teams birder, Ted Parker, specialized in identifying bird species by sound alone. He started his work day before dawn, standing in the rain under a faded umbrella, his sneakers sunk to their high-tops in mud, whispering into a microcassette recorder about what he was hearing: Scarlet-rumped cacique a fasciated antshrike two more pairs of Myrmeciza immaculata counter-singing. Dysithamnus puncticeps chorus, male and female