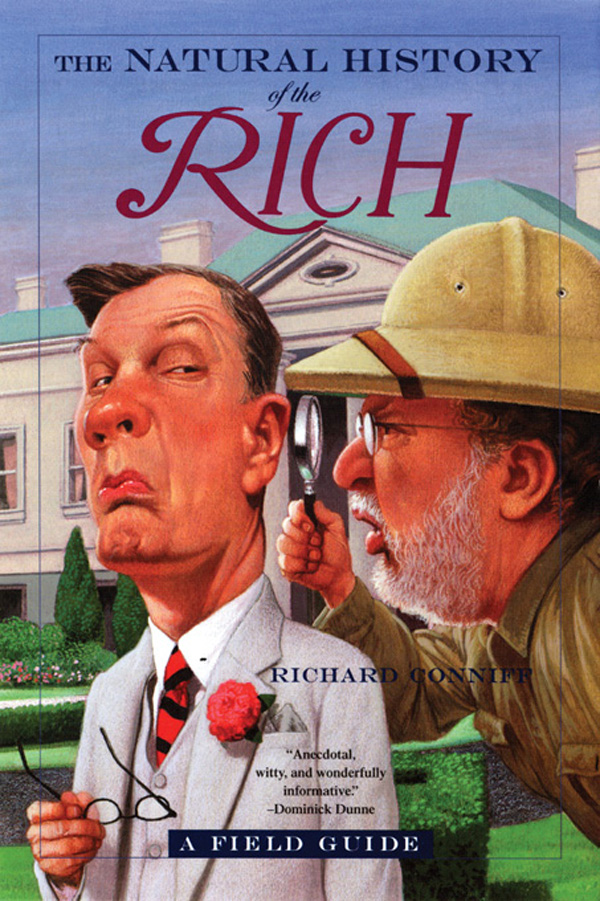

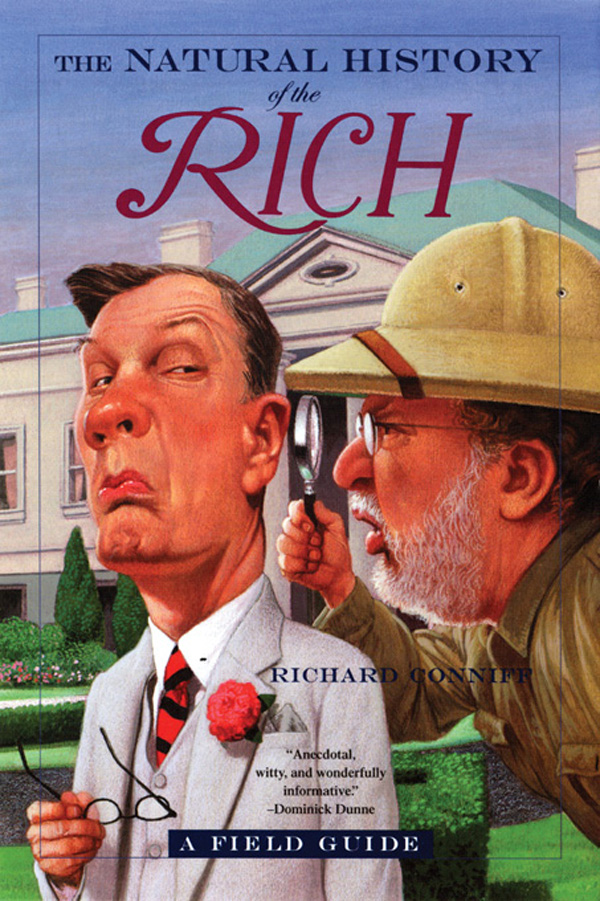

THE

NATURAL HISTORY

OF

THE RICH

A Field Guide

Richard Conniff

W. W. Norton & Company

new york london

Contents

CHAPTER ONE: Scratching with the Big Dogs

How Rich Is Rich?

CHAPTER TWO: The Long Social Climb

From Monkey to Mogul

CHAPTER THREE: Party Time

The Dawn of the Plutocrat

CHAPTER FOUR: Whos in Charge Here?

Dominance the Rough Way

CHAPTER FIVE: Take This Gift, Dammit!

Dominance the Nice Way

CHAPTER SIX: The Service Heart

Subordinate Behaviors

CHAPTER SEVEN: Why Do Rich People Take Such Risks?

Display by Grandstanding

CHAPTER EIGHT: Inconspicuous Consumption

Display by Muted Extravagance

CHAPTER NINE : Living Large

The Habitats of the Rich

CHAPTER TEN: The Temptation of Midnight Feasts

Sex, Anyone?

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Family Business

Caught in the Perpetual Dynasty-Making Machine

Acknowledgments

For their enormous help with research, I would like to thank April Reese, Jane Maclellan, and Mark Urban at the Yale School of Forestry; Jenn Dinaburg at Connecticut College; and the staff of the Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library. Thank you to Roberta Frank at Yale University and my father James C. G. Conniff for help with fine points of language. To my wife, Karen, and our children, Jamie, Ben, and Clare, thanks for tolerance of chaos and help sorting it out. For their editorial criticisms, thank you to Fred Strebeigh at Yale University, Geoffrey Ward, Jim Doherty, and Bob Poole. For generously hosting me in the course of my research, thank you to Bob Chester and Nancy Larson, Amotz and Avishag Zahavi, Janice Braeder, the Hotel Sofitel Le Faubourg in Paris, the Hilton Hotel in Frankfurt, the Excelsior Hotel Ernst in Cologne; thank you also to Virgin Atlantic for help with travel. For their ideas and advice, thank you to Gilbert Tostevin at the University of Minnesota, Sue Boinski at the University of Florida, Melissa Gerald at the University of Puerto Rico, Charlotte Beyer of the Private Investor Institute, Peter White of Citibank, Jay Hughes, and Alen MacWeeney. For assignments and encouragement along the way, thanks to Jane Berentson and Nelson Aldrich at Worth ; Don Moser, Carey Winfrey, and Beth Py-Lieberman at Smithsonian ; Steve Petranek and David Grogan at Discover ; Jennifer Reek at National Geographic ; Jason Williams and Bill Morgan at JWM Productions; and Jana Bennett at TLC and the BBC. Thank you to my agents John Thornton and Joe Spieler, whose antipathy toward Ralph Lauren caused him to suggest that I should make my natural history of the rich into a book, and to my editors Angela von der Lippe at W. W. Norton and Ravi Mirchandani at Heinemann. Thanks also to Stefanie Diaz for catching some of my mistakes.

By way of full disclosure, I must add that I have at various times done contract work, at several steps remove, developing ideas originated by CNN founder Ted Turner, Hollywood producer Peter Guber, and a computer software billionaire whose nondisclosure agreement says I will be turned to pixie dust if I reveal his name. My wife, Karen, and I were also once employed, near the bottom of the feeding chain, at a magazine owned by Kenneth Thomson. He killed the magazine in an act of mercy and put us out of work immediately after our marriage, encouraging me to begin my career as a writer. When I later visited him in Toronto, I found him to be a charmingly modest man. He even phoned ahead to his museum to make sure I wouldnt have to pay the $2 (Canadian) admission. I am grateful to them all, and if, in what follows, I occasionally bite the hand that feeds me, I trust they will regard it as a flea bite, and not the black death.

Introduction

Naturally Rich?

A telephone is to Armand what a fireplug is to a dog. He cant pass one without using it. The only difference is, he raises the receiver instead of his leg.

M RS. A RMAND H AMMER

L ETS BEGIN WITH AN EMBARRASSING ADMISSION. U NLIKE CERTAIN pioneering works in the field of evolutionary psychology, this book did not have its origins on the rock-solid foundation of an attitudinal survey. Nor did it, like many great studies in animal behavior, emerge as a result of ten thousand hours of careful fieldwork watching spiders spin webs. It started with a tip from a stockbroker. I was visiting Monaco on an unlikely assignment for National Geographic , and it felt as if I had entered another universe, where even the most casual conversation was liable to veer off at any moment into the surreal. One day, for instance, I was having a friendly drink with two young women seeking starter husbands when one of them asked the other, Does he still have the Jaguar with the matching dog?

It was a Morgan, her friend replied. Cream colored.

I asked one of them to teach me some French, and the phrase that came dancing gladly to her lips was Il a du fric , or Hes loaded. I, on the other hand, could not even open a savings account in Monaco, where the bankers gently informed me that they had a $100,000 minimum.

National Geographic ? a British stockbroker asked me one morning. Why arent you in the mountains of Papua New Guinea?

I suggested that every nation has its own anthropology, and that the native customs of Monaco were at least as exotic as those of any other hill tribe.

The stockbroker latched onto this idea instantly. You know, I go to this nightclub called Jimmyz, and its like a ritual. Every night they play the same songs, and the same girls jump up and...

I ran into the stockbroker again a few nights later at a piano bar, and he immediately began cataloguing the Mongasque anthropology all around him: Here you have the tribal mating ritual. Everyone out on display. Lots of plumage. Lots of cross-fertilization.

You sound like David Attenborough, I said.

He was holding his drink up in two hands, and the fingers flapped open to indicate the brightly clad woman on the next barstool. And here, he said, in a hushed natural history presenters voice, is the black-and-white striped, red-collared ladybird.

Just at that moment, in the smoky mirror opposite, I noticed a sleek man with an abundant mustache preened out past the corners of his mouth. He was in profile, like a side character in a Toulouse-Lautrec painting. He held up his gold lighter and, loving every gesture, stroked the flame around the tip of a fat cigar. Then, with this priapic accessory firmly in hand, he passed about the bar happily greeting his many acquaintances. In this glittering ber world of trophy wives and international arms dealers, everyone was rich and beautiful.

The stockbroker sipped his drink and had second thoughts. Were all the same beast, with or without the Cartier, he said. You can mess around with the signs and symbols, but it all comes down to the same thing as the monkeys red arse, which is, Pay attention to me.

This idea took hold in my imagination, possibly because my life had been meandering in roughly this direction for some time. I have spent much of the past twenty years writing about the natural world, for magazines like National Geographic and Smithsonian . At the same time, I have regularly contributed articles on distinctly unnatural-seeming subjects to Architectural Digest . So I have alternated between writing about the rich and about the bestial, often in close proximity. My assignments have taken me from champagne with Richard Branson at a private club in Kensington to a casual swim with piranhas in the Peruvian Amazon, and from an interview at Blenheim Palace with John George Vanderbilt Henry Spencer-Churchill, eleventh Duke of Marlborough, straight onto a plane to an audience in Botswanas Okavango Delta with an aristocratic baboon named Power. It was a toss-up which of these worlds was more perilous and, traveling between the two, it was impossible to avoid seeing certain similarities. When I got to Botswana, for instance, a biologist I was visiting confided, The rules with baboons are the same as in a Jane Austen novel: Maintain close ties with your relatives and try to get in with high-ranking animals.

Next page