HOUSE OF LOST WORLDS

RICHARD CONNIFF

HOUSE of LOST WORLDS

Dinosaurs, Dynasties, & the Story of Life on Earth

Published with assistance from the Fourth Century Trust.

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Text copyright 2016 by Richard Conniff. Photographs and illustrations from the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History copyright 2016 by Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, unless otherwise noted.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz. Set in Arno Pro and Perpetua type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in China.

ISBN 978-0-300-21163-4 (hardback : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015949553

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Endpapers: A pre-Darwinian evolutionary tree published in 1858 by Anna Maria Redfield and purchased by Yale at the time as a wall chart.

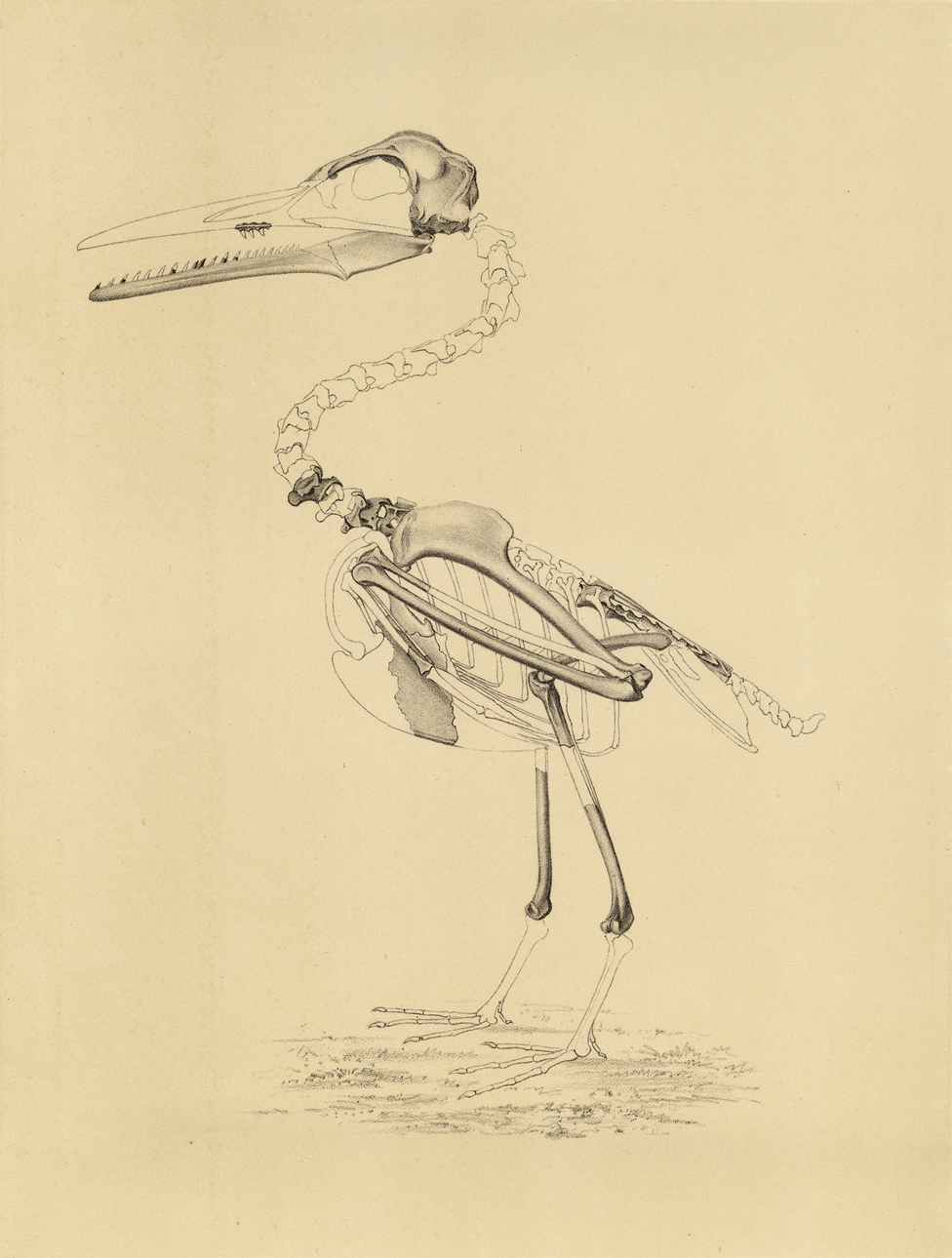

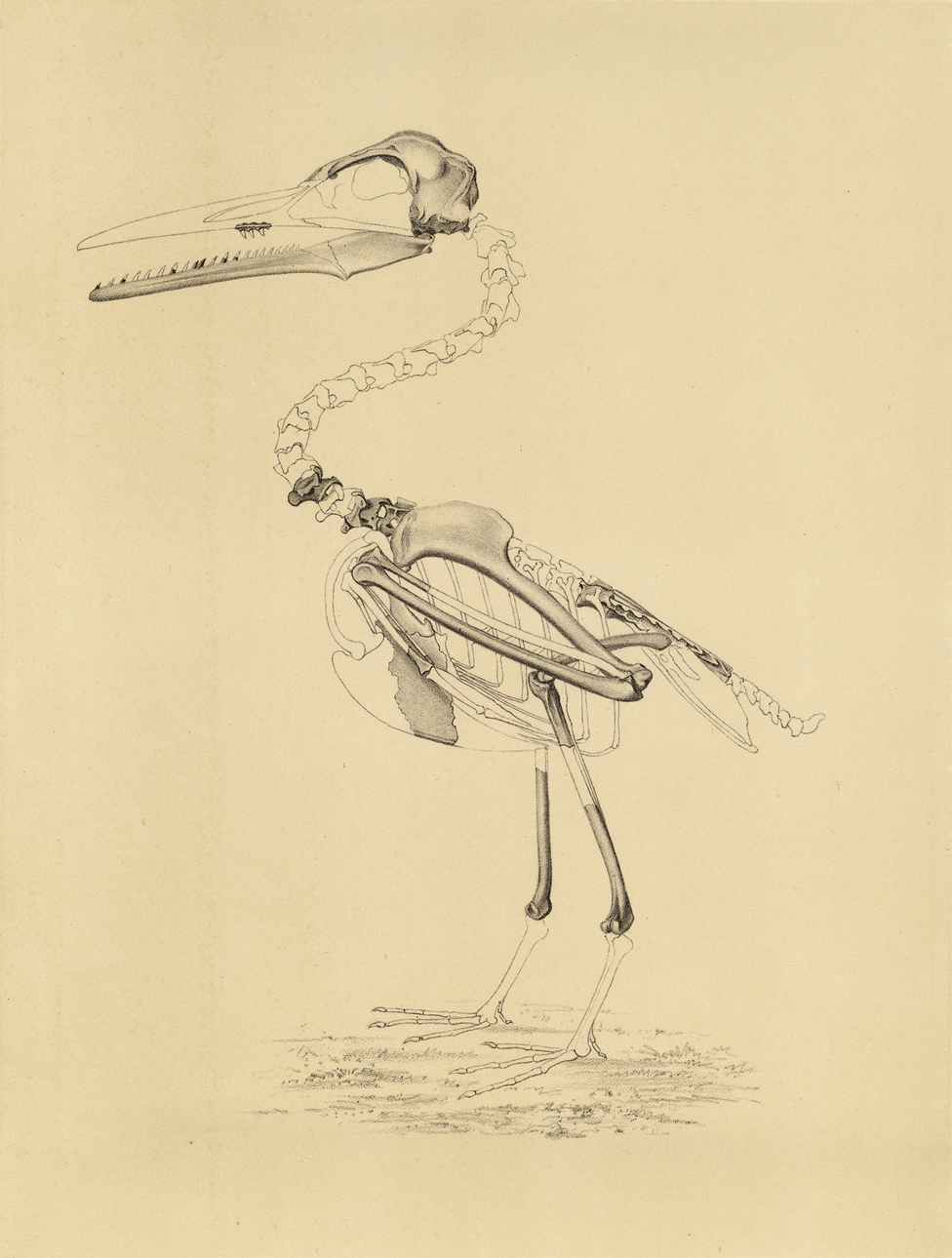

Frontispiece, : Ichthyornis dispar, one of the toothed birds with which O. C. Marsh provided crucial early proof of evolutionary theory.

: A 500-million-year-old trilobite from Pennsylvania, one of the gems in the Peabody Museums extensive collection of invertebrate fossils.

To the scientists of the

Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

CONTENTS

Introduction: Hunting for Truffles

Something about the word museum tends to make people feel very slightly dreary, but this is not a dreary museum and all museums, with my thinking, should be places of life and enjoyment and gaiety and fun because that is what education is all about.

S. DILLON RIPLEY , 1984, at the Peabody Museum

Preparator Hugh Gibb (shown here in about 1914) had the immense task of assembling many of Marshs discoveries for public display, like this Torosaurus skull, and the Pteranodon mounted behind him.

THE SCIENCE AND THE STRANGENESS BOTH begin in a parking lot on a busy street in New Haven, Connecticut, outside the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. The trees are honey locusts, an unspoken memorial to the mammoths and mastodons that once wandered there, consuming the tough, elongated pods of such trees and spreading their seeds. The vanity plate on the Subaru parked nearby, YPM 228, is the Peabodys catalogue number of a fossil trilobite, Triarthrus eatoni, which wriggled its many limbs 450 million years ago near what is now Rome, New York. (This is vanity of an esoteric variety.) The bumper sticker on another car advises, Dont believe everything you think.

There was, as I was soon to learn, plenty more strangeness and science150 years worthinside the walls of the Peabody, together with an abundance of thinking and rethinking about the world. One day, early in my research for this book, a curator proudly pointed out the collection of overeducated tapeworms extracted from incoming Yale freshmen at the beginning of the twentieth century. Also the vial of maggots from a murder victim wrapped in a rug and... But I changed the subject as quickly as possible to a lovely mobile hanging over a workbench, with a big luna moth the color of translucent jade and a morpho butterfly like a radiant blue sky, along with other moths and butterflies, all as if in flight. The insects were suspended with hairs donated by various staffers, the object being to determine whose hair was the least visible. The winner would gain the right to give up even more hair to make preserved insects airborne for an upcoming exhibit.

To be honest, I love this sort of thing (even the tapeworms). Robert Louis Stevenson once described his boyhood manner of reading as digging blithely after a certain sort of incident, like a pig for truffles. In his hunger for bright images and bold action, the young Stevenson foolishly skipped past eloquence and thought, character and conversation, which I think most adult readers would regard as the truffles. But the pig analogy strikes me as exactly right about the oinky, snuffling character of the writers work, and for me the Peabody Museum was a mother lode of truffles.

One day, for instance, I came across a somewhat plaintive letter about luggage left behind with a U.S. Cavalry lieutenant named A. L. Varney at an outpost in the Wyoming Territory in 1872: I am still holding the Fossil Mosasaurus for you, the lieutenant wrote to paleontologist O. C. Marsh, but as I expect to be ordered from this station soon please advise me what to do with it.baggage of a high order, a Mosasaurus being a prehistoric sea monster up to sixty feet in length. Fortunately for Lieutenant Varney, it was just the skull, now safely preserved as YPM.00327.

Another day, in the Historical Instruments Collection, I became fixated on a saliometerthat is, a saliva meter. It was an instrument I had not previously imagined to have existed. It was the one Ivan Pavlov used in his classic conditioning experiments on salivary response in dogs. (Pavlov gave it to Yale psychologist Robert Yerkes, from whom it made its way to the Peabody Museum.) In the Vertebrate Zoology Collection, I became enchanted with the story of the sled dog Togo, hero of a 1925 race to deliver diphtheria antitoxin through impossible weather conditions to a stricken Alaskan community. Togo lives on as the continuing inspiration for the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Racebut his skeleton is now lovingly preserved in climate-controlled conditions at the Peabody Museum.

Truffle hunting, it turns out, has long been a familiar pursuit to the Peabody Museum staff. A vertebrate paleontologist there once remarked that the best collecting he had ever done was not in the Badlands of the American West nor in Inner Mongolia but in the basement of the Peabody Museum. The discoveries lie waiting even nownot just in the basement but almost anywhere in the cluster of buildings around the main museum as well as in archive and storage facilities in the suburb of West Haven. In 2002, for instance, researchers browsing through the paleontological specimens noticed a distinctive five-inch-long tooth. A Colorado collector had sent it in 1874 to O. C. Marsh, who was too swamped with other specimens to make sense of it. This was regrettable, as it has turned out to be the earliest known specimen of the ber-predator Tyrannosaurus rex (King of the Tyrant Lizards). Thus Marsh, an intensely possessive and competitive collector, missed out on the discovery, and the species had to wait another thirty-one years to be describedby one of his hated rivals.

Somewhat more humbly, a curator browsing through the botanical collection a few years ago noticed a liverwort specimen marked as the type of its speciesthat is, the individual by which the species was first described and defined. It looked like a bunch of dried schmutz, as preserved liverworts will do. Then the botanist looked more closely at the identifying tag and found it had been collected by one Charles Darwin during his travels aboard HMS

Next page