COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Donald R. Prothero

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54646-15

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Prothero, Donald R., author.

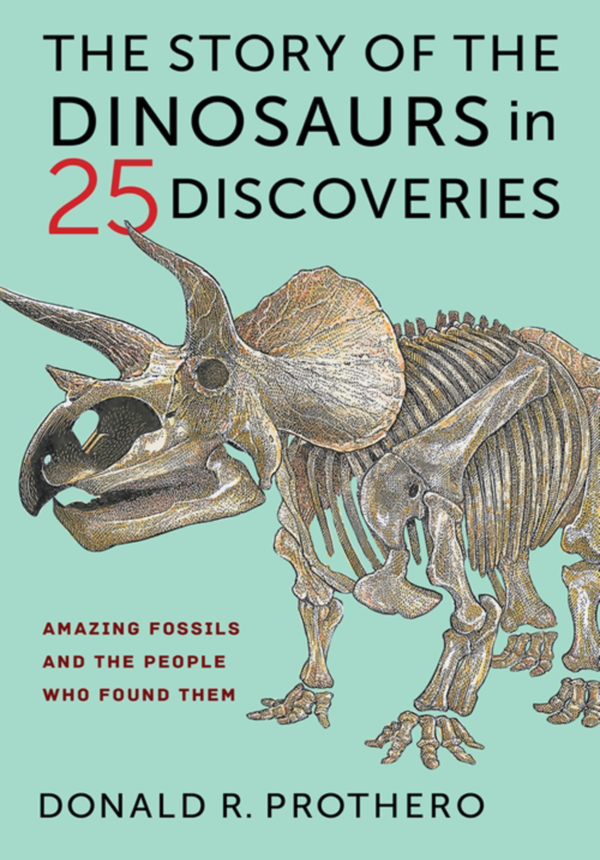

Title: The story of the dinosaurs in 25 discoveries: amazing fossils and the people who found them / Donald R. Prothero.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018044694 | ISBN 9780231186025 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231546461 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: PaleontologyHistory. | Paleontologists. | Dinosaurs.

Classification: LCC QE705.A1 P76 2019 | DDC 567.9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018044694

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Julia Kushnirsky

Cover image: Trudy Nicholson

Frontispiece: Courtesy of Roy Troll

I am one of those kids who got hooked on dinosaurs at age four and never grew up. I knew I wanted to be a paleontologist as soon as I understood what the word meant. However, when I was a child in the 1950s and early 1960s, there was almost no dinosaur merchandise to buyjust a handful of kids books and few plastic toys. One or two amateurish movies and TV shows had a few seconds of stop-motion Claymation dinosaur effects, advanced CG dinosaur movies certainly didnt exist in the 1950s or 1960s, and there were only a few sci-fi movies with crude stop-motion animation. Moreover, my classmates all through school did not seem interested in dinosaurs, and I was considered somewhat of a freak for knowing all those complex names. It was so unusual that they had me lecture the sixth graders about dinosaurs when I was only in fourth grade.

Today that has all changed. Dinomania has been growing since at least the late 1970s and 1980s, and its difficult to pinpoint the specific cause. A huge media onslaught of dinosaurs exists today, and a gigantic array of dinosaur merchandise is available. Perhaps it was the effect of the Dinosaur Renaissance (and they focus on the opposite sex, sports, video games, and other high school obsessions.

This huge upsurge in interest has been a mixed blessing for vertebrate paleontology. We are certainly more popular and respected then when I was trying to make it into the profession, but the job market is still horrendous. With so many eager students now, only one in one hundred will land a job as a professional research paleontologist in a museum or university. Not only are jobs lacking, but there is little or no grant funding for all but a fortunate few. Most vertebrate paleontologists struggle to get field funds or even to pay for simple supplies for camping or prep work.

No jobs, no money, few chances to find funds to do muchits not a pretty picture. But the profession chugs along, with hundreds of graduate students spending 10 years of their lives in college with no prospect of a job at the end of the line, and hundreds of scientific papers are published each year. A few of these discoveries are mentioned in the science media if they concern dinosaurs or other charismatic extinct beasts such as mammoths or saber-toothed cats. But as my graduate advisor, Malcolm McKenna, put it, there are two types of people in paleontology: the rich and dedicated, and the poor and dedicated. Nobody goes into the field to get rich, thats for sure! A few of the leading members of the professionEdward Drinker Cope, Henry Fairfield Osborn, Childs Frick, Wann Langston (and Malcolm McKenna)came from wealthy families, but most do not. You either have money already and can afford to practice an esoteric profession that doesnt find oil or coal or make big money, or you do it because you love paleontology and wouldnt consider any other career despite the bad odds and poor pay.

I persisted through high school, college, and six years of graduate school at the American Museum of Natural History and Columbia University, the best place in the world to get the right background and connections in vertebrate paleontology at that time. Most graduate programs had terrible track records for placing their students, but nearly all of my classmates at the Columbia/American Museum program succeeded in getting good jobs. We had the best collection in the world to work from, and we were trained by the leading paleontologists in the world, particularly my advisor, Malcolm McKenna.

As an undergraduate working with Mike Woodburne at the University of CaliforniaRiverside, I realized there were far more opportunities to do many different kinds of interesting projects with fossil mammals than there were with dinosaurs. This remains true today, even though the number of new dinosaur discoveries has skyrocketed. In addition, a lot of people are trying to study dinosaurs, so the field is very crowded. This is a big contrast with the available research opportunities in fossil mammals, with thousands of specimens available for study if you know where to look. I have done a few projects with dinosaurs here and there and tried to keep up with the incredible pace of new discoveries and new ideas, so I feel on top of most of the major developments over the past 50 years. I also started teaching a dinosaur course at the university level for the first time, which has brought me up to date much faster than anything else could.

After the great reception for my books The Story of Life in 25 Fossils and The Story of the Earth in 25 Rocks, I thought it was about time to do a dinosaur book using the same format. Each chapter focuses on a particular discovery or genus or specimen of scientific and historical significance, and it weaves a story around it of the interesting people who found it, what they thought, and a summary of what we now think about this or that dinosaur. Paleontology is replete with colorful characters and great human interest stories, from the eccentric William Buckland, to the nasty feud between Gideon Mantell and Richard Owen, to the Bone Wars between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, to the aristocratic Henry Fairfield Osborn or the humble Walter Granger, or to the legendary collectors Jos Bonaparte and Barnum Brown, or the wild gay Transylvanian Baron Franz Nopcsa, who tried to become king of Albania.