Don Paterson - Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary

Here you can read online Don Paterson - Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Faber & Faber, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber & Faber

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

for Nora

S ince their first publication in 1609, Shakespeares Sonnets have appeared in countless editions, and have been translated into every major living language, as well as many minor, dead, synthetic and intergalactic ones, too. Basque, Latin, Esperanto and Klingon have all have played host to these verses, written 400 years ago by a bald Englishman who didnt even consider poetry his main literary medium. The Sonnets have been awarded the ultimate accolade human culture can bestow: proverbialism. A Shakespeare sonnet is almost as much a synonym for love-poem as Mona Lisa is beautiful woman. As soon as something becomes proverbial, however, everyone feels like they already know it. In recent times, this has relieved us of the trouble of reading the Sonnets properly.

About a year ago, I decided that Id stop pretending to myself and to my students that I knew these poems better than I did. Id made a couple of fairly thorough passes in my twenties, and knew a respectable number of the Sonnets well, and had a few by heart. However, a hideously exposed bluff at a party, much too painful to recall here, prompted me to re-examine my avowed familiarity. I have the charmless habit of imputing my own larger ignorances to everyone else otherwise theyd be too much for any one man to bear but this time, I had the strong suspicion that I might not be completely alone. A straw-poll of my non-academic acquaintances quickly confirmed as much. Shakespeares Sonnets are not quite poetrys A Brief History of Time i.e. a book everyone owns, and no one has finished but theyre close. We all know Mark Twains definition of the classic, something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read. We might add, less memorably, that a classic is a book you can safely avoid reading, because no one else will admit they havent read it either. Dont get me wrong: everyone said they loved the Sonnets. They just tended to love the same ten poems. (My control, incidentally, was Tennysons In Memoriam. Everyone who said they loved that knew it backwards and inside out.) Was this because there are only ten good poems? Were those ten really the best ten? What about the other hundred and forty-four? Even more worryingly, more than one apparently well-read individual remarked Theyre addressed to a man, I believe, as if the information had only recently come to light through ingenious advances in 21 st-century cryptography. So I started to make a list of questions: do the Sonnets really contain what we believe them to contain? Do we still talk about love in the same way, and are these poems still useful to us? Do they still move us, speak to us, enlighten us? Is their reputation deserved, or have they simply hitched a ride on the plays? What are these poems to us now?

I formed a vague plan to read one or two sonnets a day, keep a record of my thoughts, feelings, gut reactions and reflections as I reread them, and make notes on their arguments and form, on their poetic technique and compositional method. I revised these notes as little as possible, and hope that this book has retained the feel of the reading diary that it was. Essentially, I tried to read the poems in a way which was sympathetic to them, and suited the questions Id posed. Compared with every other available commentary this book was written, quite intentionally, in a tearing hurry, and no doubt it shows. A book with different aims would have been compiled in a far more cautious and considered fashion, and there are plenty of excellent commentaries which are, written by people for whom caution and consideration come far more naturally. Ill talk about why I went about it in this way in a moment, but first, a word about the Sonnets themselves.

Ill give no more than the very briefest introduction to the Sonnets here. All the business of their authorship, composition, dramatis personae, publishing history and controversies will be touched on in the course of the commentary itself. Ive also included two short essays as appendices; one on the form of the sonnet, and one on the Sonnets metre. (If youre after an informative, scholarly and reliable single essay on the Sonnets, I can heartily recommend those with which Colin Burrows, Katherine Duncan Jones and John Kerrigan introduce their own editions.)

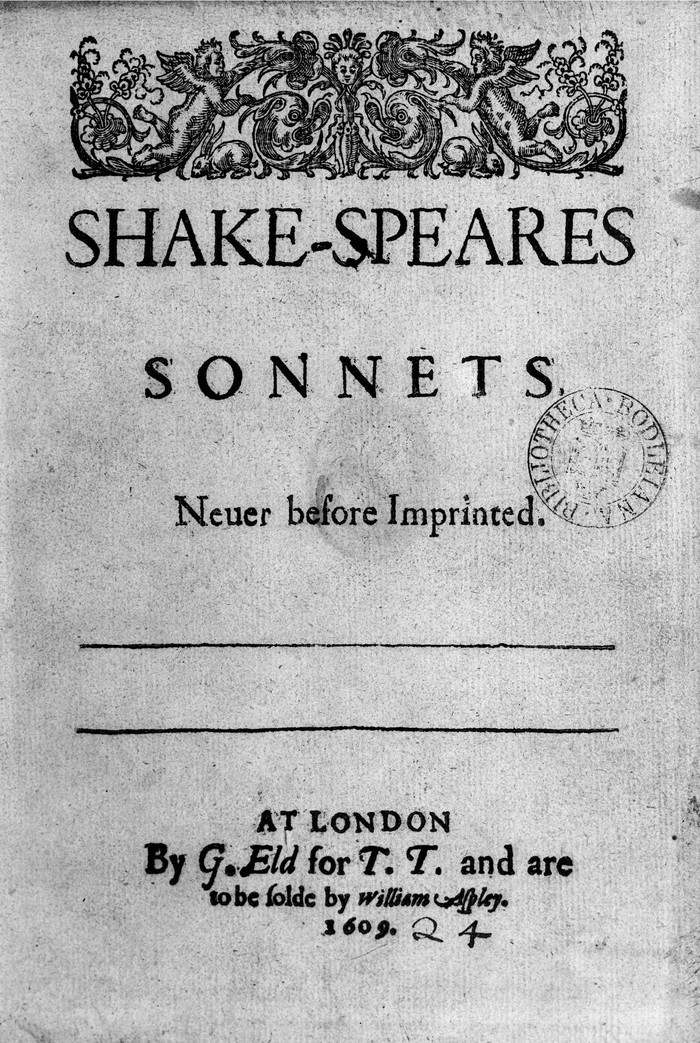

The Sonnets are a collection of one hundred and fifty four poems, first published in 1609 as SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS. Never before imprinted. A bit of a fib, that, as early versions of Sonnets 138 and 144 had previously appeared in a something called The Passionate Pilgrim, a dogs dinner of an unauthorised miscellany, published by William Jaggard in 1599, claiming to be by Shakespeare but containing the work of several other authors too. In the 1609 volume we also find A Lovers Complaint, a long poem written in rhyme royal, a seven-line stanza introduced by Chaucer into English: a rather lovely, weird poem it is too. This first printing of the Sonnets is generally referred to as the Quarto edition (the Q, hereafter), and was published by Thomas Thorpe, which we know from his having entered it in the Stationers Register, the nearest thing the Elizabethans had to copyright law.

Controversy still rages over whether the Q was authorised by WS or printed without his permission, and nothing can be definitively proven either way. However, I fall very strongly into the theres absolutely no damn way Shakespeare didnt authorise it camp, as the Q has been ordered in a meticulously careful, sensitive and playful way that can only indicate the authors hand. (Reasoning: publishers care, editors care but none of them care that much.) The Sonnets seem to have been composed between 1582 and their date of publication, 1609, i.e. between Shakespeares eighteenth and forty-fifth birthdays. This, I admit, is a staggeringly useless piece of information. However the 1582 date refers to an isolated piece of juvenilia, Sonnet 145, while the so-called dating sonnets seem to imply that the larger part of the project was likely over some time before 1609. Most commentators still argue that the poems were written in a six or seven-year span in the mid-1590s. True, Frances Meres refers to them in 1598 The witty soul of Ovid lives in mellifluous & honey-tongued Shakespeare, witness his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugard sonnets among his private friends, &c. but Im wholly suspicious of the claim that they were all composed in this period.

What we do know is that the Sonnets were part of an extraordinary fashion for sonnet-cycles in the 1590s. These were wildly competitive affairs. The bar had been set high by Philip Sidney with the 108 sonnets of Astrophil and Stella, which had been in private circulation from the early 1580s. A poet would be judged on more than the length of his sequence, of course, but size counted for something, and padding was epidemic. Shakespeares own sequence falls into three principal sections. It begins with the so-called procreation sonnets, a rather dull run of seventeen poems where WS urges an unnamed young man to marry and reproduce, so his loveliness will survive; these sound somewhere between a warm-up exercise, a commission, an apprentice-piece and an elaborate exercise in seduction, and Ill explore all four possibilities. (I apologise in advance for my lack of enthusiasm for these poems; it seems a bit much to begin a book in such a negative way, and still expect you to keep reading on but the alternative would have been lying about their quality.)

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary»

Look at similar books to Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Reading Shakespeares Sonnets: A New Commentary and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.