A time has come and gone.

captured in a song.

another world.

Another world.

Chapter One

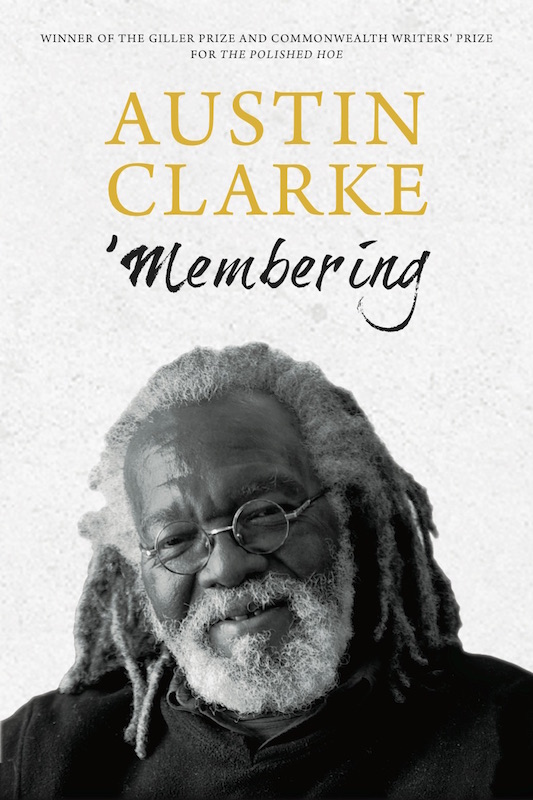

I am sitting in my study on a Friday afternoon in 2004, forty-nine years after I came limping through a hurricane whose name I cannot remember, although it is the name of a woman, and I always remember the names of women, but this is 1955, on the twenty-ninth day in September, fifty years later, almost to the day, in this same weather that used to be called, and could be called Indian Summer, a term which to me, a novelist, is filled with romantic notions and presumptions, but which the pervading decency of political correctness, like the fury of the hurricane I member the name we called it by now! Janet! Janet, Janet, Janet! Hurricane Janet. I have known many Janets. And all of them were harmless, beautiful women but here I am, in this study that looks across a road well travelled in the rushing mornings to work, and hardly travelled with such anxiety and intent during the hours that come before the rush to work, walked on, and peed on, by the homeless, and the prostitutes and the pimps, and the men and women going home to apartments in the sky, surrounding and overlooking Moss Park park, as I like to call it. Moss Park park is where life stretches out itself on its back, prostrate in filthy, hopeless, bouts of heroism and stardom, for these men who lie on the benches and the dying grass, are heroes to themselves and to one another, in a pecking order that is full of right-eous daring, and righteous chances of stupidity like crossing the road in front of speeding cars that put the brakes at the last minute on with a squeak. The image of a smashed head on the shining bonnet of a Mercedes-Benz is not on the menu for tonights dinner in Cabbagetown; or the delay caused by the dying words of the homeless man about his residence in a filthy halfway house behind the bastions of Victorian and Georgian townhouses that hide this degradation from the fleeing man in the German-made automobile.

Such homelessness as politicians like to call this layer of detestation greets me every day on the green grass cleaned by the morning and the dew, like a set of teeth passed over by a smear of toothpaste; or by warm water seasoned in salt; or by bare fingers that had dug during the night in the five minutes ticking off on a Rolex watch, or counted off in seconds by the friction of a French-leathered hectic moment behind the fences of the townhouses, deep into the panties of the woman who stands like a sentry at the corner of two streets, punctual and reliable as a security guard, and whose colour or cleanliness he wisely cannot see in the dark, leaf-shaking night hidden by the trees that have no tongue in the chastising speechless mouth of satisfaction.

And I wonder why these men with their picked-out women, all standing in the darkness of street corners shaded by trees and the darkness of their own intentions should choose such a little, such a small, short hiatus from their lives of homelessness or lovelessness?

I have been homeless once. In a most dramatic manner, with a knock on the door, in the rough, brutal manner of the bailiff; but this is nothing to boast about. I saw my homelessness in the colour of black and white: racism, at its most brutal and unfeeling and uncompromising display. But I saw it also in the insistence that I would overcome this temporary reversal of fortune. I saw it, too, as a revisiting of the importance or the fatalism associated with Fridays. Fridays in my early life in Barbados, were days of terror, when I had to face homework at Harrison College that was almost the equal of one terms work at Combermere School for Boys, the previous second grade I attended. Harrison College was a first grade government school. At Harrisons, which is what we called our school, a normal Friday afternoons homework for me as a boy in the Lower Sixth Form of Modern Studies (I was specializing in Latin and English grammar and English literature, with subsidiary subjects of Roman history and religious knowledge), meant learning two chapters of the Acts of the Apostles; two chapters in Roman history; one hundred lines of Virgils Aeneid Book II, two chapters in Caesars Gallic Wars ; two chapters of Livy Book XXI; and as our Latin master (Joe Clarke, no relation of mine!), who had no idea of the lives we lived away from Harrison College, always suggested, Well, you can open your book and look at a few chapters of Tacituss Histories , after you have pushed your Sunday dinner plates aside.