Acknowledgments

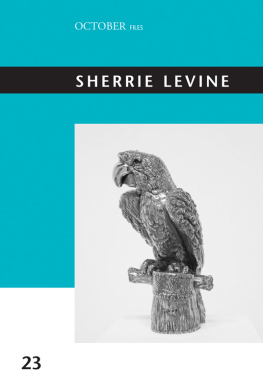

I have spent more than a few paragraphs writing about the difficulty Sherrie Levine's art practice poses to beginnings, and in the pages that follow I look closely at the ways in which her work troubles ideas of origins and defers first instances. And yet this book has a beginningit was born in Los Angeles in 1983 in Richard Kuhlenschmidt's small ground-floor gallery in the Los Altos Building on Wilshire Boulevard, where I first saw Levine's photographs after Walker Evans. I spent a lot of time hanging around the gallery and met Joe Bishop and Larry Johnson there; I am indebted to them both, and to Kuhlenschmidt, for a conversation about Levine's work, Pictures, and postmodern criticism that continued on and off for a year. I reviewed that exhibition for Artforum, one of the first pieces I published there; it benefited from the advice and patience of David Frankel, then the magazine's reviews editor.

The discussion that began in Kuhlenschmidt's gallery grew to include a much larger circle of friends, teachers, and students in Los Angeles over the next few yearsat openings and house parties, in bars and classrooms. My thanks to Richard, Rosamund Felsen, and Margo Leavin for hosting those openings, and for letting me spend time in their galleries, and to Joel Wachs for inviting me to dinnerand to all of them and to Christopher Knight for their conversations. The students I taught in the early days at UCLA let me work through theoretical writings that were as new to me as they were to themin front of them and in real time; it was a remarkable group of students, many of whom are now friends: Uta Barth, Ellen Birrell, David Bunn, Nora Halpern, Martin Kersels, Simon Leung, Lane Relyea, and Jan Tumlir. And I learned a lot from the artists and writers I met in and around CalArtsstudents, faculty, and alumni: Michael Asher, Nancy Barton (whose bookstore at LACE was a godsend), Cindy Bernard, Dorit Cypis, Mike Kelley, Steve Prina, Allan Sekula, Christopher Williams, and especially Sande Cohen, who was and continues to be a generous teacher, reader, and friend. My day job after CalArts and UCLA was at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and the discussion continued there in earnest with some smart young curators: Kerry Brougher, Ann Goldstein, and Elizabeth A. T. Smith. I was lucky to have met Douglas Crimp, Hal Foster, Tom Lawson, and Susan Morgan early on in Los Angeles, where they came as visitors, speakers, and writers. They were all connected in one way or another to debates around postmodernism, and to Levine and her work; they all appear in this book, and I have learned much from them. I am grateful, too, for their hospitality whenever I came east, and to be able to count them now as longtime friends.

This was a beginning, but as befits Levine's strategy, and her insistence on reworking origins and redoubling firsts, it didn't become one until some years later, at the University of Rochester, when I returned to my review and what I had seen at Kuhlenschmidt's gallery. There, first in response to an invitation from Louise Neri at Parkett and then for Sharon Willis's seminar Feminism and Visual Culture, I rewrote my encounter in the gallery in the language of psychoanalysis; that is, it became a beginningcausal and structuringonly after the fact, only after other kinds of knowledge were acquired, which is, of course, Freud's recipe for Nachtrglichkeita word I learned in Rochester. My thanks to Sharon and to her colleagues and mine: Mieke Bal, Cristelle Baskins, Norman Bryson, David Deitcher, George Dimock, Michael Ann Holly, Grant Kester, Walid Ra'ad, and Janet Wolff. When the seminar paper was finally published in October in 1994much improved through its encounters (and mine) with Hal Foster and Rosalind Kraussit was dedicated to Kaja Silverman; parts of it appear here in , on Levine's painting, have also been previously published, in Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, in 2004; I thank Stephen Melville for his invitation, and for his ongoing friendship and support.

This book was written in Charlottesville, and my colleagues at the University of Virginia and friends in town have heard much of it in faculty seminars and over coffee. I thank them allpast and presentfor the comments and advice: Matthew Affron, Paul Barolsky, Sarah Betzer, Daniel Bluestone, Sheila Crane, Jonathan Flatley (whose departure was a loss not just for me, but for the level of interdisciplinary discussion at UVA), Douglas Fordham, Carmen Higginbotham, Barbara Clark Smith, David Summers, and William Wylie. I am indebted to Larry Goedde, chair of the department, for his support of the project; while it was not completed in a timely fashion, that it was completed at all I owe to a University of Virginia Sesquicentennial research leave. And to the department's Visual Resource Center: Leslie Rahuba and Louise Putnam have been exceptionally helpful and gracious, solving all manner of digital problems. I thank my graduate students, who over the years have also listened to a good deal of this in seminars on the copy and on the 1980s, and have given me much to think about: among them, Lisa Frye Ashe, Leslie Cozzi, Mary Leclre, Monica McTighe, Melissa Ragain, and Rebecca Schoenthal. Thanks to Sofia LeWitt, I was able to spend significant amounts of time in New York during my leave, and in addition to her, it is my pleasure to thank Johanna Burton, Tim Griffin, David Joselit, Paul Mattick, Jr., and Katy Siegel for their ideas, and for their friendship and hospitality.

I owe a great deal to Stephanie Fay, my editor at University of California Press, and I thank her for her patience and care; it is a pleasure to work with her. The readers she chose for the still fairly rough manuscript were both supportive and incisive; I thank Liz Kotz in particular for her comments and advice, most of which I have taken into account and which have, I think, improved things significantly. I am grateful for the advice and assistance of the librarians at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and I owe a great debt to the people at Paula Cooper Gallery, who have given me access to their files and helped to track down works and images; special thanks to Paula, her director, Steve Henry, and to Seth Erickson and Davina Semo. My thanks to Barbara Kruger and Olivier Mosset for their permission to reproduce their artworks here, and for their support of the project. All of the rights and permissions personnel I bothered at museums and galleries were gracious and helpful: special thanks to Ron Warren at Mary Boone Gallery, James Woodward at Metro Pictures, and Holly Frisbee at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Publication of Art History, After Sherrie Levine has been supported by generous grants from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and from the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and the Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies at the University of Virginia.

One reason to write a book is to be able to thank people in public, and I want especially to thank the people who have been closest to me, and to this, for the longest time. My sincere thanks to Sherrie Levine, of course, for all the reasons I spell out in the introduction, and for still more. To Craig Gilmore and Ruthie Wilson Gilmore, who are, as Ruthie has written, so close as to be fictive kin, many thanks, once again and always. Finally, this book could not have been written without the love, support, and good humor of my wife, Janet Ray, and my children, Max and Rosalietwo signal events of the 1980S. They have lived with it around the house for what must seem like forever, and have deferred a number of projects so that this one might be completed. I thank them for their patience and understanding.

SPONSORING EDITORS

Stephanie Fay, Kari Dahlgren

PRODUCTION EDITOR

Laura Harger

TEXT

10/13 Sabon

Next page