NonCommercial as defined in this license specifically excludes any sale of this work or any portion thereof for money, even if the sale does not result in a profit by the seller or if the sale is by a 501(c)(3) nonprofit or NGO.

Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Parts of this book appeared in various forms in a few places. A chunk of was published in the San Francisco Bay Guardian as The Corporations Have You: The Matrix Trilogy Freaks Out Over Info-Capitalism.

This book project took far too long, so I have a lot of thanking to do.

Thanks to my old colleagues and mentors in the academy: My dissertation committee, Richard Hutson, Susan Schweik, and Carol Clover, offered helpful comments and encouragement when this book was still in ridiculously bad shape. Several others helped me learn what I needed to (whether they knew it or not): Michael Berube, Laura Kipnis, Gerald Vizenor, Kathy Moran, Fred Pfeil, Henry Jenkins, and the brazen Constance Penley. Others in the academy, who shall remain nameless, also guided my intellectual development immeasurably. You know who you are.

Thanks to Ken Wissoker at Duke University Press for being a patient, kind, and thoughtful editor.

Thanks to the San Francisco Bay Guardian crew (past and present), especially Tim Redmond, Lynn Rapoport, Cheryl Eddy, Susan Gerhard, John Marr, and zillions of picky readers: you have truly encouraged me to print the news and raise hell. Thanks to the Bad Subjects gang for being totally rad: Joel Schalit, Charlie Bertsch, Megan Shaw Prelinger, Jonathan Sterne, Doug Henwoodyou rock! Keep on refusing to answer the hail. And thanks to my fellow freedom-loving geeks at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who encouraged me to choose a Creative Commons license for this book and always provide me with endless discussions of cheesy movies in between bouts of agitating against large entertainment companies, ruthless rights holders, and the government.

Thanks to my many families: the wonderful, goofy Burnses; the supergenius Kuppermans; my long-suffering housemates Ed and Ikuko Korthof; and my father, who took me to my first monster movie.

Last but not least by any means, my profoundest love and adoration to Charlie Anders, Jesse Burns, and Chris Palmer, who have helped me through much worse things and are the best friends I have.

INTRODUCTION

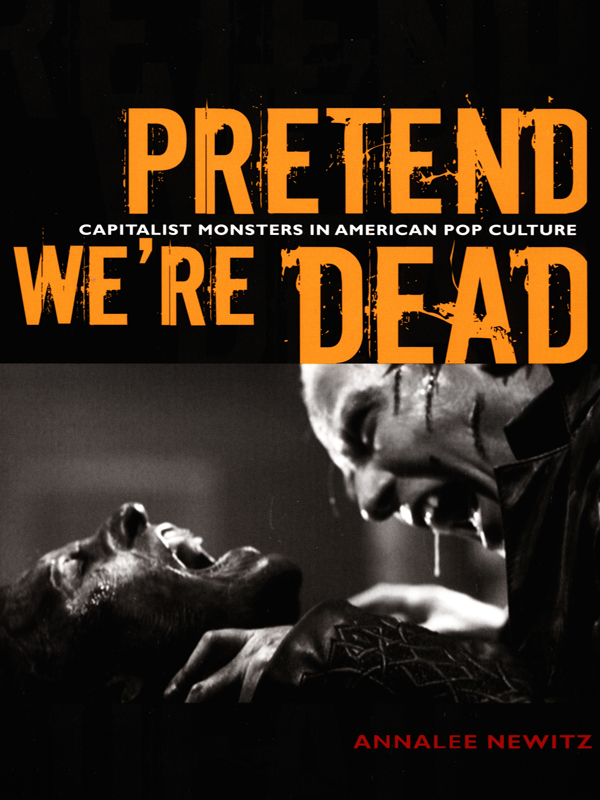

Capitalist Monsters

Theyve got us in the palm of their big hand When we pretend that were dead They cant hear a word we said When we pretend that were deadL7, from Bricks Are Heavy (1992)

At the turn of the century, critics hailed two movies as exciting reinventions of the horror genre: The Sixth Sense and Blair Witch Project. Both are about dead people who refuse to stay that way. The signature line from Sixth Sense, Haley Joel Osments whispered, creepy I see dead people, was an instant pop cultural meme. T-shirts with this phrase and morphed versions of it (I see stupid people) were everywhere at the dawn of the new millennium, as were parodies and rip-offs of M. Night Shyamalans terse, quiet movie about a little boy plagued by needy ghosts.

Osments character Cole sees spirits who cannot rest until they get some kind of closure on their lives. Hes begun to go insane when Malcolm, a child psychologist, helps him understand that the dead are not there to hurt or frighten himthey just need to be heard by one of the only human beings who can. Every dead person has a story that Cole must interpret. Only by talking with these terrifying creatures, who often appear to him soaked in blood or with their brains dripping out, can he bring peace to himself and his preternatural counterparts.

Of course, some ghosts could give a crap about closure. Certainly this is the case with the bloodthirsty spirits who haunt the remote Maryland woods in Blair Witch.When a bunch of art students decide to slum it around the countryside to get footage for a sarcasm-laced film theyre making about the legend of these spirits, they discover what documentary filmmakers have known for almost a century: the natives dont appreciate their condescending attitude. Murdered in mysterious, supernatural fashion, the students in Blair Witch are reduced to little knots of hair and teeth because theyve refused to heed stories the locals tell about the Blair Witchs power to kill from beyond the grave.

Nothing is more dangerous than a monster whose story is ignored.

Like all ghosts, the dead people in Sixth Sense and Blair Witch come to the human world bearing messages. They remind us of past injustices, of anguish too great to survive, of jobs left undone, and of truths we try to forget. Gloopy zombies and entrail-covered serial killers are allegorical figures of the modern age, acting out with their broken bodies and minds the conflicts that rip our social fabric apart. Audiences taking in a monster story arent horrified by the creatures otherness, but by its uncanny resemblance to ourselves.

One type of story that has haunted America since the late nineteenth century focuses on humans turned into monsters by capitalism. Mutated by backbreaking labor, driven insane by corporate conformity, or gorged on too many products of a money-hungry media industry, capitalisms monsters cannot tell the difference between commodities and people. They confuse living beings with inanimate objects. And because they spend so much time working, they often feel dead themselves.

The capitalist monster is not always horrifying. Sometimes it is, to borrow a phrase from radical geneticist Richard Goldschmidt, a hopeful monster. Instead of telling a story about the destructiveness of a society whose members live at the mercy of the marketplace, this creature offers an allegory about surmounting class barriers or workplace drudgery to build a better world.

Regardless of whether its story is terrifying or sweet, capitalist monsters embody the contradictions of a culture where making a living often feels like dying.

Economic Disturbances

Stories about monstrosity are generally studied from psychoanalytic and feminist perspectives, but I argue that an analysis of economic life must be synthesized with both in order to understand how we define monsters in U.S. popular culture. Capitalist monsters are found in literature and art film as well as commercial fiction and movies. Certainly we can find dramatic differences between its literary and B-movie incarnations. But, even as they cross the line between one form of media and another, the stories fundamental message remains the same: capitalism creates monsters who want to kill you.

Its crucial to acknowledge that the people creating the books and movies I analyze in