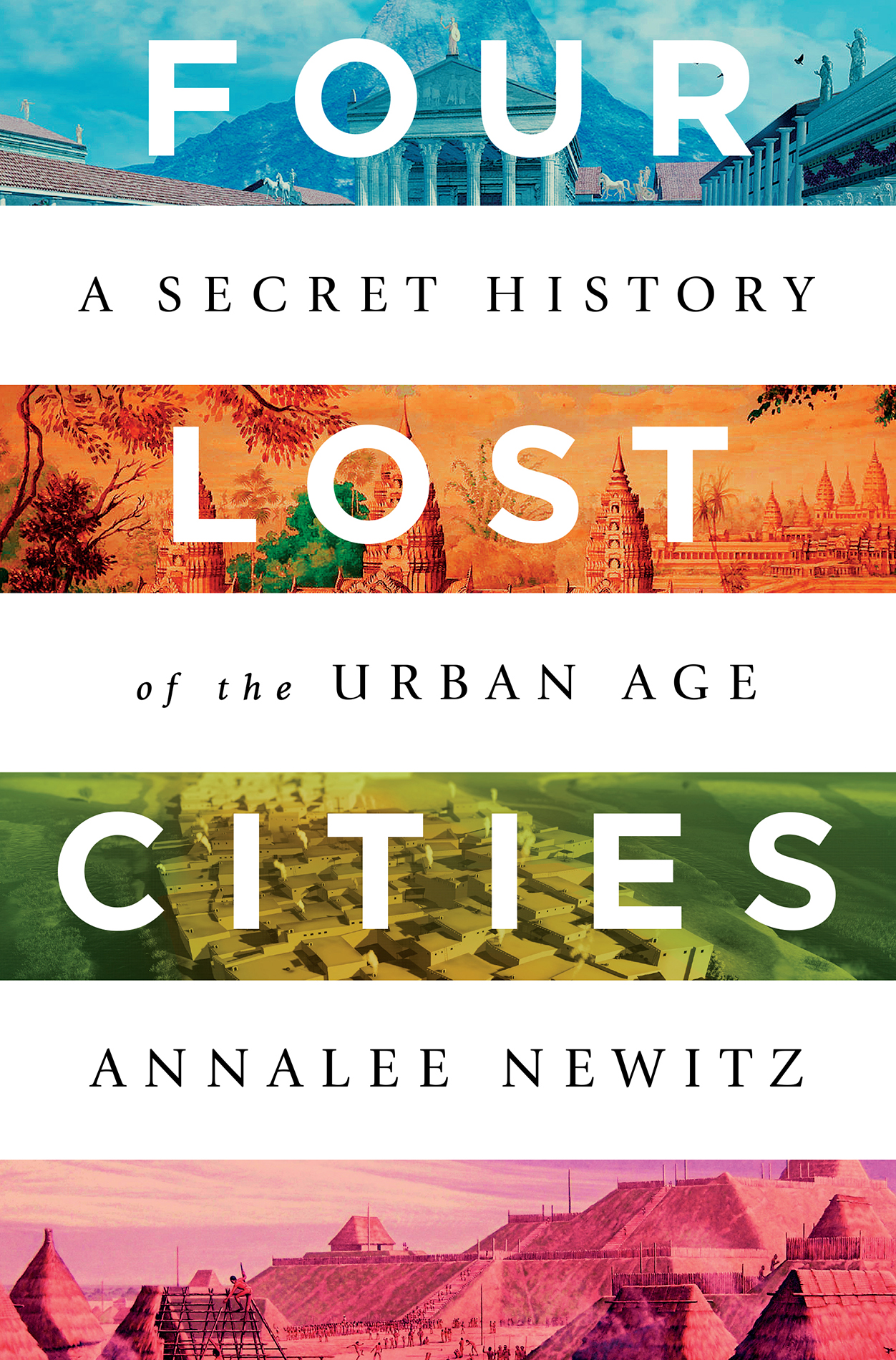

Annalee Newitz - Four Lost Cities

Here you can read online Annalee Newitz - Four Lost Cities full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: W. W. Norton & Company, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Four Lost Cities

- Author:

- Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Four Lost Cities: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Four Lost Cities" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Four Lost Cities — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Four Lost Cities" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

LOST

CITIES

![]()

A SECRET HISTORY OF THE URBAN AGE

Annalee Newitz

This book is given as a humble offering to Iaso, Acesco, Hygieia, and Panacea.

But most importantly it is dedicated with love to Chris Palmer, who survived.

LOST

CITIES

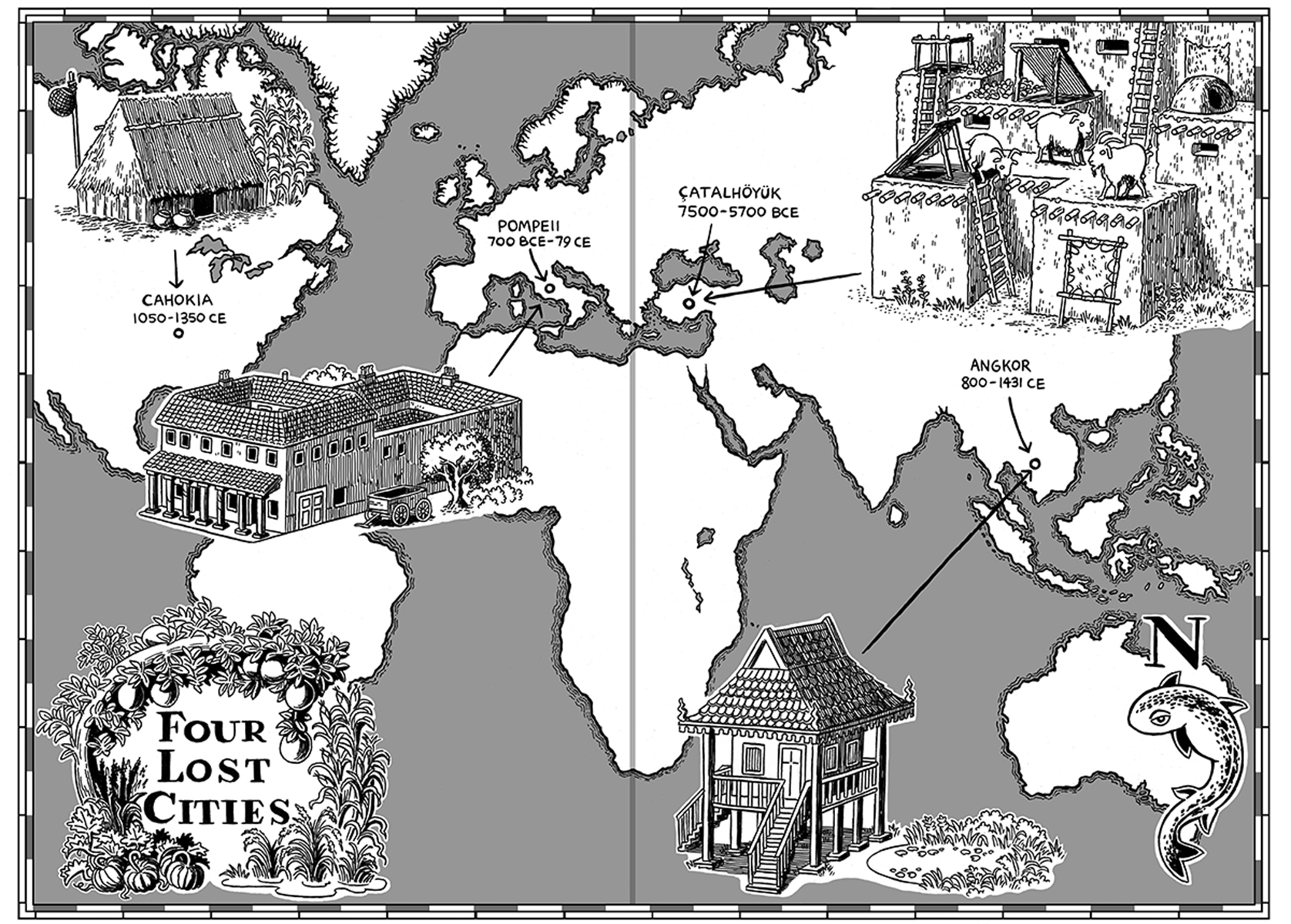

I stood on the crumbling remains of a perfectly square island at the center of an artificial lake created by hydraulic engineers 1,000 years ago. Sunlight played over an eroded sandstone wall. Though this was the dry season in Cambodia, unseasonable rain storms had cleared the air of smoke from local farmers annual field burning. In the distance, I could see the sculpted towers of Angkor Thom and Angkor Wat, architectural marvels of the ancient capital of the Khmer Empire. Boasting nearly a million residents at its peak, Angkor was once the worlds most populous city. And I stood near its center. Beneath my feet was the Mebon, an 11th-century Hindu temple-island, built during the reign of King Suryavarman I in the middle of an enormous reservoir called the West Baray. That morning, the barays southern shore was dotted with a few motorboats whose pilots would take visitors out to the Mebon for a couple bucks. It isnt a short journey: the rectangular West Baray is eight kilometers long, roughly the length of three jet runways at a typical airport. A millennium ago, when workers finished digging the baray, the Mebon temple at its heart was the sole patch of dry land for kilometers around.

Behind its ornate stone gates, the Mebon enclosed another, smaller reservoir, invisible to all but the select few who were permitted to land on its shores. At its center floated a 6-meter-long bronze statue of Vishnu reclining, enormous head resting on one of his four arms. Pilgrims traversed waters within waters to pay homage to this Hindu god, who brought forth life from the sea when the world was made. You might say the Mebon is a monument to the spiritual power of water. But its also testimony to the ingenuity of Angkorian laborers who kept the annual monsoon floods contained with large reservoirs like the West Baray, and slaked the citys thirst during the dry season with a system of canals that diverted water from distant mountain rivers.

Surrounded by shimmering water and weathered blocks from the temple excavation, I tried to imagine looking out over the baray centuries ago, seeing festive boats full of Khmer locals and dignitaries from neighboring kingdoms bearing fragrant bundles of flowers and incense. It must have been astonishing, I thought. But my romantic fantasy about this place didnt last long.

I cant believe how much they screwed this up, Damian Evans said, gesturing in frustration at the baray. Evans is an archaeologist with the French Institute of Asian Studies whose work over the past two decades has dramatically changed our understanding of Angkors urban grid. A sandy-haired Australian with a quick smile, hes spent decades writing about the sophistication of the Khmer Empire. But hes also keenly aware of its failures.

Evans pointed to a faded map of the landscape on a wooden placard next to us, part of a display detailing a reconstruction of the Mebon thats currently underway. Looking at elevations, it was obvious that the east-west oriented rectangle of the West Baray slopes gently with the landscape, causing the east end of the reservoir to fill while the west end stayed dry. As a result, the baray rarely looked like the shining rectangular lake Id imagined. Instead it would have been more like a deep pool that trailed off into a ragged, muddy edge. But this wasnt because Khmers engineers were incompetent. They could have built on a level surface, but the king wanted his engineers to stick with an east-west orientation that suited his gurus, Evans explained. The Khmer believed that grand structures like the kings reservoir should be oriented along the same trajectory that the sun and stars took across the sky. Put another way, King Suryavarman I cared more about auspicious astrological signs than good hydroengineering. This reservoir was an ancient boondoggle. Over the long term, the West Baray became a template for Angkorian city planning, leaving its swelling population with faulty water storage during turbulent periods of climate crisis.

If you substitute the word politics for astrology, Evans observation could have been made about the design of any number of cities over the past 1,000 years. City leaders pour resources into beautiful spectacles for political reasons, rather than providing good roads, functioning sewers, relatively safe marketplaces, and other basic amenities of urban life. As a result, cities may look awe-inspiring but arent particularly resilient against disasters like storm floods and drought. And the more a city suffers from the onslaughts of nature, the more contentious its political situation becomes. Then its even harder to repair shattered dams and homes. This vicious cycle has haunted cities for as long as theyve existed. Sometimes the cycle ends with urban revitalization, but often it ends in death.

At Angkors height in the 10th and 11th centuries, its kings controlled thousands of workers. These were the people who built the cities palaces, temples, roads, and ill-conceived canals. Though most of this construction was intended to glorify the Khmer kings, it also helped ordinary inhabitants thrive as farmers even during the dry season. But in the early 15th century, the region was stricken by drought, followed by catastrophic flooding that destroyed Angkors poorly designed water infrastructure at least twice. As the city began to fall apart, the chasm between its rich and poor grew wider. Within decades, the Khmer royal family moved their residence from Angkor to the coastal city of Phnom Penh. This was the beginning of the end for a city whose kings had dominated vast parts of Southeast Asia for centuries, including todays Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos. The citys population had drained away from Angkors downtown by the 16th century, leaving behind small villages and farms surrounded by Angkors decaying urban grid. The kings palaces were abandoned, and the barays became mere depressions in the leafy forest floor. Only a skeleton crew of monks remained to care for the Khmer Empires legendary temples.

In the 19th century, a French explorer named Henri Mouhot claimed hed discovered the lost city of Angkor. Though other European visitors of the period acknowledged that monks still lived in the Angkor Wat temple enclosure, Mouhot wrote a popular travelogue that suggested he was the first to stumble upon a lost civilization. No human had seen it in centuries, he claimed, and it was full of picturesque wonders to rival those of ancient Egypt. It was an easy myth to perpetuate. Westerners hungry for adventure stories were eager to believe Mouhot when they saw pictures of the citys dramatically collapsing temples, the stones in their walls forced apart by bulging tree roots. From the beginning, Angkors status as a lost city was manufactured by the media, despite all evidence to the contrary.

The lost city is a recurring trope in Western fantasies, suggesting glamorous undiscovered worlds where Aquaman hangs out with giant seahorses. But its not just a love of escapist stories that makes us want to believe in lost cities. We live in an era when most of the worlds population lives in cities, facing seemingly unsolvable problems like climate crisis and poverty. Modern metropolises are by no means destined to live forever, and historical evidence shows that people have chosen to abandon them repeatedly over the past eight thousand years. Its terrifying to realize that most of humanity lives in places that are destined to die. The myth of the lost city obscures the reality of how people destroy their civilizations.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Four Lost Cities»

Look at similar books to Four Lost Cities. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Four Lost Cities and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.