Contents

Guide

T his is a book about a program, not about me. That is why there are lots of extracts from The Science Show indicating conclusions that may seem surprising, but over time may turn into received wisdom.

First accolade goes to Sharon Carleton and John Spence (ABC archives) who found all the extracts. Sharon is also a longstanding Science Show contributor of immense range and flair. She has never refused a request, however irksome.

David Fisher has been with me for years (he is the team people sometimes refer to) and does so much that the new technology demands but which many dont notice in terms of effort: the pods, the websites, the photos, the transcripts, the program production and he has other programs (The Naked Scientists) to look after. David has found so many references I needed.

Others who have produced the program over the years have been Halina Szewczyk, Nicole Gaunt, Polly Rickard, Barbara Hucker, Mary Mackel and Leigh Dayton. Of the contributors Pauline Newman is a star, having been in the BBC Science Unit she is now a professor of science communication at Arizona State University and still does reports for us. Others helping over the decades have been Lynne Malcolm, Norman Swan, Joel Werner, Richard Aedy, Kirsten Garrett, Jonathan Nally, John Challis and Johnnie Merson. Peter Pockley, who founded the ABC Science Unit in 1964, provided many a brave report.

So many brilliant broadcasters have made whole Science Shows over the years including David Ellyard, Anne Deveson, Matthew Crawford, Anna-Maria Talas, Julie Rigg, Martin Redfern, and those whove made whole series, are acknowledged within this book.

Our technical people are different each week gone are the days when someone was dedicated to the show. But I salute them all.

I am grateful to those at ABC Books for help in dealing with a manuscript begun the day after I left hospital following two rather shattering cancer operations. I did not, exactly, have chemo brain but it felt like it. I am ordinarily a master of allusion, as a former editor of mine once put it. I know what I mean and too quickly assume everyone else does as well. Writing ever such succinct radio scripts on my typewriter every day doesnt help such tendencies towards terse, cryptic communication and I am delighted Lachlan and Helen felt free to tell me so.

The ABC is like a difficult lover: often infuriating but impossible to put aside. Its broadcasters are simply wonderful and I owe them every skill I possess. The scientists themselves are a never-ending inspiration and Australia is blessed, more than it deserves, with such superb ones, old and young. But our listeners are what it is all about, now all over the globe. I know it is naff to point to ratings, however, our podcast figures alone towards the end of 2015, when you combined The Science Show and Lynne Malcolms All In the Mind (also from the Science Unit) came to over SEVEN MILLION . We must be doing something right.

Finally, I have a tendency, usually thwarted, to fall prey to fatal diseases. Norman Swan has saved me more than once, over the years, and my lady, Dr Jonica Newby, rescued me at the start of 2015 with CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, powerfully delivered. Both have been magnificent through these rugged times, as have my former wife and very good friend Pamela Traynor and my children Jessica and Tom. This book is for them.

T his book is based on about 2040 programs involving 14,280 stories and 7140 professors. It has involved 110,160 minutes or 1836 hours (76.5 days) of continuous broadcasting. These figures are, of course, imprecise, but whos to tell? What it means is that the task is nigh impossible, like telling the story of a long war with 95 per cent of the process apparently dreary routine me sitting with recordings, razors and sticky tape (or nowadays tracking green waves on screen), editing for hours or else, the remaining 5 per cent, involving thrilling encounters with celebs discussing the meaning of life. There is no coherence about the story of a radio program, especially when spread over four decades. So this book is more a personal conversation than a solemn history.

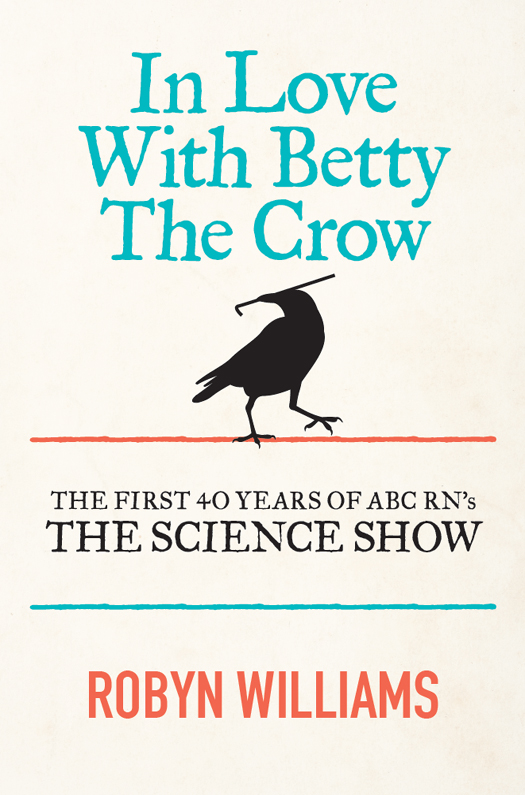

Why am I in love with Betty the Crow?

Well, I am immensely fond of animals but this does not mean I failed as a Real Man to grow up and turn properly to apparatus, flexes and accelerators (My engineer father said, there is physics and all the rest is stamp collecting). Biology is now every bit as sophisticated and mathematical as physics. No, animal behaviour is one main field where developments have been spectacular in recent decades, with significant ramifications, and the sight of Betty the New Caledonian crow becoming an engineer and solving problems with insight, creativity and planning makes me cry with delight. (Other birds, and plenty of dogs, have also broken boundaries.) So, you can pin them up with all those vaccines, deep dives, space shots and techno-wizardry at the cutting edge of science, feeding the addiction that has kept my colleagues and me at the scientific mike for so long.

It has all been with the ABC, but not exclusively so. The public may perceive barriers between employees of Aunty and our commercial friends, but this is illusory. At our level, were all mates. And, over the years, how it has all changed! I started in a kind of collegial diaspora, with the ABC spread all over Sydney and the masters of the separate colleges were like powerful barons with retinues, rows of tapping secretaries and very long daily commitments called lunch.

Today we occupy an endless open-plan IT factory, with the barons of drama, religion, science and sport long gone while we toil away silently with unlimited schedules, looking sometimes like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, buffeted by anxiety and machinery, insatiable screens and airtimes.

Doing this, we are also giving the public a false sense of security about legacy because we are hiding what it really costs to do our jobs. We are always packing microphones to take on holidays in case an opportunity abroad materialises or an exotic location offers broadcasting possibilities. In 2014 I went on a private trip to South America and came back with two entire Science Shows about Galapagos and Machu Picchu. A taxpayer-funded perk? No way. When being treated for cancer a couple of weeks before I started writing this book, I interviewed Sir Philip Campbell, Editor-in-Chief of the journal Nature, while reclining in my hospital room. The nurses were taken aback when I made them leave. But you cant miss a story! Our successors will wonder how the hell we managed it.

* * *

Modern science is very young despite its intellectual foundations in ancient Greece. The transition from the classical approach to a profession is barely two hundred years old. This means that the role of scientists is still uncertain, evolving, hard to pin down. For this reason, I have invariably included history and biography in my reporting. Not only does it make science more human, it also gives it context.

In early 2014, as I said, I travelled to the Galapagos Islands with my family and read a lot about Charles Darwin on the way. I was struck by his age when the good ship Beagle first set sail; he was barely twenty-three. On the way, in Peru, I pointed out a waiter of the same age to some of my fellow travellers and they were suitably staggered by his youthfulness. But while boy Darwin was away on the Beagle, in 1833 at Cambridge, Darwins alma mater, the Reverend William Whewell actually coined a name for those who did research in science. They were no longer considered to be natural philosophers, because they got their hands dirty and handled apparatus even dead animals almost trade, one might say! Whewell chose scientist, though some thought it sounded too much like atheist. (By the way, the question about what to call these new professionals was put by poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.)