FABULOUS SCIENCE

F ABULOUS SCIENCE

Fact and fiction in the history of scientific discovery

John Waller

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX 2 6 DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai

Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi

So Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto

and an associated company in Berlin

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

John Waller 2002

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 0-19-280404-9

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

T.J. International Limited

Padstow, Cornwall

To my parents, with all my love

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Each chapter in this book draws heavily on the original scholarship of leading historians of science. The scholarly papers I consulted are the results of thousands of hours of laborious research, conducted by historians who often began their investigations confident of the veracity of the myths they would later explode. To pay these researchers their due, and to suggest where the reader may go to read further, I have included a brief statement on my sources at the end of the volume. In many instances I have added my own analysis and commentary, so any resulting errors or infelicities must of necessity be my responsibility alone.

This book is also indebted to the scholars who have stimulated my fascination for the discipline of history from school through university: Thomas Eason, Jeffrey Grenfell-Hill, Simon Skinner, Maurice Keen, the late Michael Mahoney, Joe Cain, Janet Browne, and Everett Mendelsohn in particular. The students who I have helped instruct at Oxford, London, and Harvard universities inspired me to bring these stories to a wider audience. And the staffs of Imperial College Londons Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine and Londons Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine drew my attention to much of the scholarship upon which this book is based. The archival staffs of the Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine, Harvards Baker Business Library and Countway Medical Library, the Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum at St Marys Hospital, the Royal Astronomical Society, and the California Institute of Technology very kindly allowed me to reproduce photographic images.

I am also profoundly grateful to Richard and Penny Graham-Yooll, Adam Hedgecoe, Darian and Alison Stibbe, Jon Turney, and Jane, Michael, and Susan Waller for their excellent editorial advice and encouragement. My father, Michael Waller, has been a wonderful source of inspiration, illumination, and guidance. Michael Rodgers and Abbie Headon at Oxford University Press and copyeditor Sarah Bunney have also been most helpful. Finally I would like to thank my wife, Abigail, for her unstinting affection and support.

John Waller, December 2001

INTRODUCTION | W HAT IS HISTORY FOR?

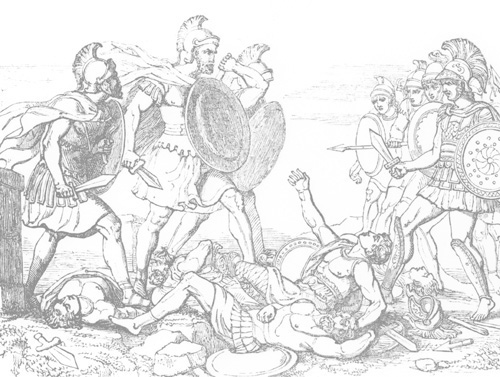

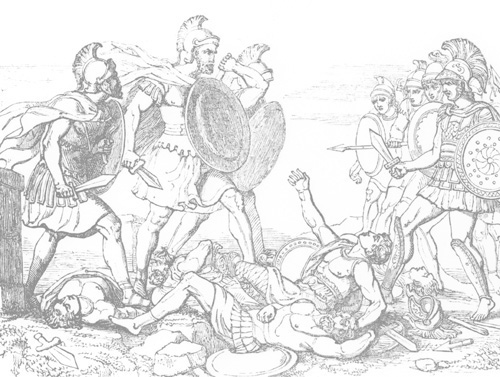

Previous page: The dauntless three guard the bridge over the Tiber, from Macaulays epic poem Lays of Ancient Rome.

W HAT IS HISTORY FOR?

Remark all these roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it.

Oliver Cromwells instruction to Lely

on the painting of his portrait.

The great biologist Louis Pasteur suppressed awkward data because it didnt support the case he was making. Gregor Mendel, the supposed founder of genetics, was no Mendelian. Joseph Listers famously clean hospital wards were actually notoriously dirty. Alexander Fleming misled the world about his role in the discovery of penicillin. And Einsteins general relativity was only confirmed in 1919 because an eminent British scientist ruthlessly massaged his figures.

These are some of the recent findings of historians covered in this book. In writing it my primary aim has been to bring to the attention of a wider audience the fruits of a generations research into the history of science. But, although the scholarship I draw on seriously challenges the reputations of major scientific figures, this is not an exercise in pointless iconoclasm. Above all, this book aims to offer insights into the conduct of scientific debate, the securing of scientific immortality, and the complex interplay between scientists and the worlds in which they operate.

In highlighting these warts and all studies, I am firmly positioning myself on one side of a great historical divide. As the divide in question runs through the entire historical enterprise, I can illustrate it with an example taken from Classical Rome. These are the opening lines from Horatius, the first in Thomas Babington Macaulays epic series of poems, Lays of Ancient Rome, written in 1842:

Lars Porsena of Clusium

By the Nine Gods he swore

That the great house of Tarquin

Should suffer wrong no more.

By the Nine Gods he swore it,

And named a trysting day,

And bade his messengers ride forth,

East and west and south and north,

To summon his array.

A favourite of the Victorian schoolroom, this poem still has the power to quicken the pulse and enthuse the reader with martial pride. What seems to make the Lays of Ancient Rome doubly stirring is its historical veracity. Macaulay drew his great poem not from his admittedly fertile imagination, but from the Roman histories themselves. These tell how in the sixth century BC the enemies of Rome led by the Etruscan Lars Porsena had fought, sacked, and plundered their way to the shores of the Tiber. At last, their greatest prizethe eternal city itselflay all but defenceless before them. The battle-hardened troops of a long and glorious campaign gazed across to a city facing slaughter, rapine, and ruin. But a quick-thinking Roman Consul had seen a way to save his people. The plan was simple. The only bridge over the Tiber was barely wide enough for one man to pass at a time. So a handful of men could hold the bridge long enough for it to be cut away behind them. As these valiant soldiers plunged to a watery death, they would have the consolation of fulfilling every Roman matrons deepest desire for her son: his giving his life to save the Nation. This notwithstanding, so tough was the challenge that at first only brave Horatio accepted it. Then two others followed his example.

Next page