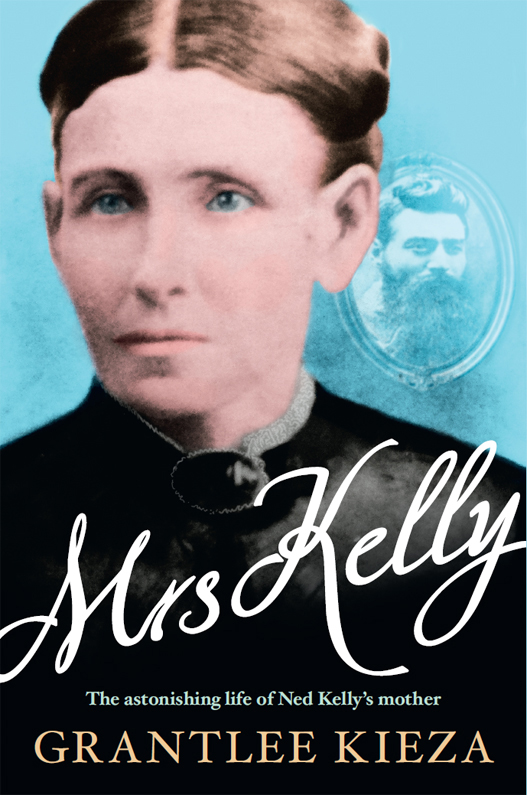

A free-flowing biography of a great Australian figure

John Howard

Clear and accessible... well-crafted and extensively documented

Weekend Australian

Kieza has added hugely to the depth of knowledge about our greatest military general in a book that is timely

Tim Fischer, Courier Mail

The author writes with the immediacy of a fine documentary... an easy, informative read, bringing historic personalities to life.

Ballarat Courier

For Kevin and Pat McDonald, my friends.

CONTENTS

Guide

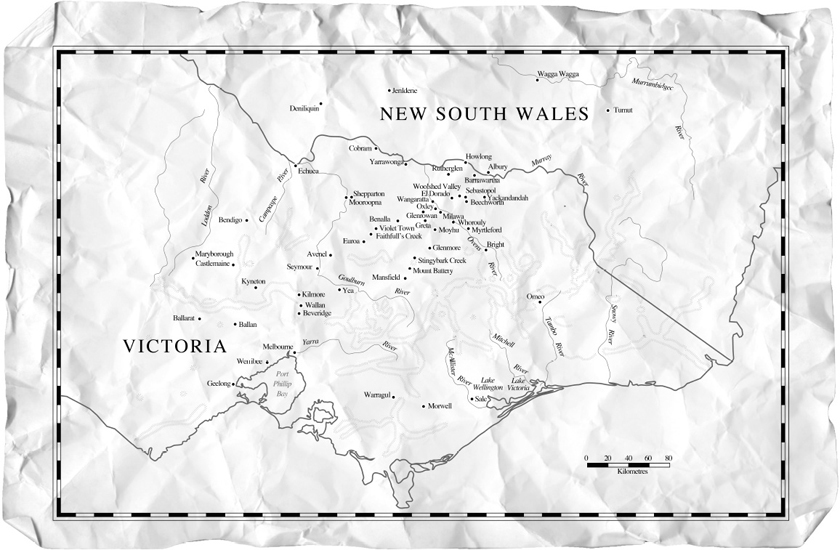

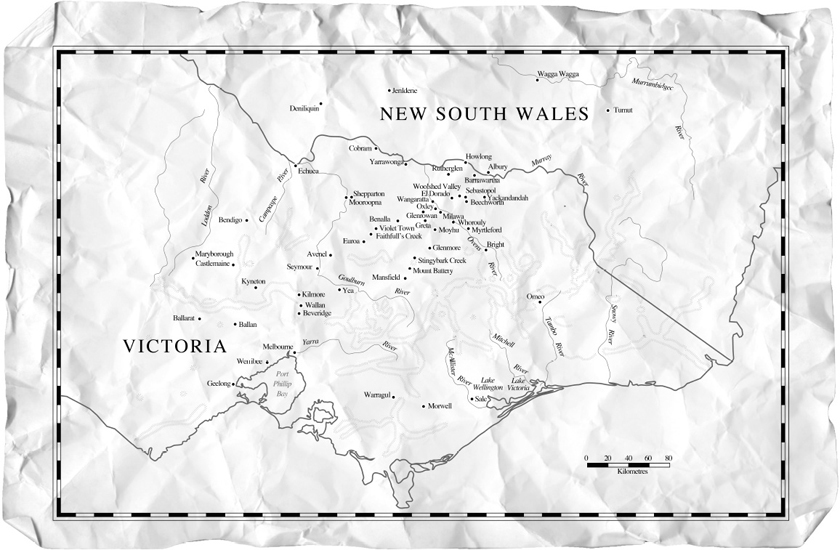

MARCH 1923, ELEVEN MILE CREEK, GLENROWAN WEST, VICTORIA

Mrs Kelly seized an old shovel that was at the fireplace, and rushed at me with it... She rushed at me with this shovel and made a blow at me, and smashed my helmet completely in over my eyes; and as I raised my hand to keep off the shovel Ned fired a second shot, and it lodged in my wrist.

CONSTABLE ALEXANDER FITZPATRICK RELATING HIS DISASTROUS CONFRONTATION WITH THE KELLY FAMILY

I believe these outrages would never have happened if it had not been for the shooting of Constable Fitzpatrick, and the consequent anger and indignation of the Kellys at their mother having received that severe sentence.

FREDERICK CHARLES STANDISH, VICTORIAS CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF POLICE, ON THE KELLY OUTBREAK

T HE LITTLE OLD LADY PEERS through the windows of the tumbledown shack as clouds of red dust and a low rumble announce the arrival of an automobile. One of those fancy convertibles.

The smell of eucalyptus wafts down from the grey-blue Warby Ranges in the distance, and a few sheep graze nearby, quietly unconcerned by the mechanical invasion. A couple of sinewy rust-coloured kangaroos bound out in front of the swanky new machine, then, with a few thrusts of their powerful hind legs, they disappear into the scrub.

Ned Kellys mother has never ridden in a motor car before, and, staring at the vehicle as it hobbles its way across the uneven ground, she wonders if she might have a try behind the wheel.

A lifetime ago, when Mrs Kelly was a fiery young girl with alabaster skin and a mane of thick black hair so long she could sit on it, she could ride a horse like the wind coming off the snows of Mount Buffalo. No bloomin fence in Australia could hold her, and even when she was a middle-aged, widowed grandmother she was charged with hooning through the streets of Benalla on horseback.

Now she wonders how fast this automobile could go, with all the horsepower they say is packed into those smoky engines.

Her small, piercing, grey-blue eyes have dulled after all shes seen in her 91 years, but Mrs Kelly watches keenly as the car bumps along towards her front door.

Detective Fred Piggott has come up all the way from Melbourne to see her, an odd thing to do given the Kelly familys long and violent history with authority. Victorias most famous lawman is paying a visit to the mother of Australias most infamous outlaw, bringing a journalist to interview her, even though police have rarely received a warm welcome here. There has always been a public fascination with the outlaws, but now in 1923, there is renewed interest in the Kellys with Godfrey Cass, son of the Melbourne Gaols former governor, starring as Ned in not one, but two recent motion pictures about the gang.

Ellen will never forget the heavy boots of the police trampling the sounds of silence on a bitterly cold night 45 years ago when the notorious Mrs Kelly, as they called her back then, was dragged away from her three-day-old daughter in handcuffs.

The police would break down her door and terrify her young daughters, turning milk tins over and pouring flour onto the floor, demanding to know the whereabouts of her boys Ned and Dan, the cop-killers.

The law hanged Ned while she was housed with him in Melbourne Gaol. She had tried to look after him all his life worked for him, cleaned for him, sold sly grog for him, probably lied for him more times than she can now recall. But when he needed her most she was helpless and unable to protect him, listening like a frightened mouse for the clanging sound of the gallows trapdoor that spelled the end of his short, violent life.

Her younger son Dan, always trying to prove himself in his hand-me-down clothes, had died surrounded by police as they called on him to surrender. After the police set fire to his refuge all that was left of Ellens boy was a charred, smouldering stump on a sheet of bark.

Her boys turned Victoria on its head during a spree of murder and robbery that made them monsters to some, martyrs to others but as this roofless Model T Ford comes to a stop outside the house, Ellen reminds herself that those troubles were a long time ago.

All the fight has left the old lady now. Crippled by arthritis and the unyielding weight of time, she struggles to stand upright with the help of a thick stick and the arm of Big Jim Kelly, Neds grey-bearded brother.

Jims still a big man, and while he was once as ferocious as Ned, in and out of Australias hardest prisons from the age of 13, time has smoothed out his rough edges, soothed his hate and blind rage, as it has for old Mrs Kelly. For years Jim has devoted himself to giving his mother some comfort at the end of a long life of almost unbearable sadness and conflict.

Now both watch carefully as Fred Piggott and the journalist Bartlett Adamson walk cautiously towards the front door of the little house. A creeper sprawls over the front veranda and the place looks like it might tumble in on itself with a sudden rush of wind. Mrs Kelly and Big Jim are a reclusive pair, but they knew Piggott when he was stationed in Glenrowan 20 years earlier, and they welcome their guests into this humble home.

It is hard for the visitors to imagine this tiny, bent-over woman as the same one who, with her 12th baby at her breast, was sent to Melbourne Gaol to do three years hard labour for beating a policeman over the head while Ned shot him. But Adamson makes a mental note that in spite of her extreme age, her hollowed cheeks and sunken jaw, there is a tilt almost of defiance about the poise of her head. Her straight nose, the sharp, firm moulding of the chin, and a glance rather eagle-like from under the shadows of her brows suggest the inner fire still burns.

She has lived an extraordinary life.

As a child, Ellen watched the convict ships sailing past her home on the coast of Ireland bound for the Great South Land, and she has lived long enough to see motor cars roaring along these old bush roads, and aeroplanes buzzing overhead faster than even her sons could fly on their stolen horses.

She has survived two husbands and more than half of her children, and seen both war and peace in her remote neighbourhood.

Ellen tells the visitors that this is Jims house but she has lived around here for 56 years, the first 10 of them in a shanty a mile and a half closer to Greta.

Back then, as a young widow with seven hungry children and no way of supporting them, she took possession of an old abandoned hut and fashioned a home for her brood. She took two young lovers, had more babies and sold grog illegally to keep her children fed. She farmed the hard, harsh land and watched, heartbroken, as her three oldest sons sunk deeper and deeper into crime, fighting a police force determined to break their spirit.