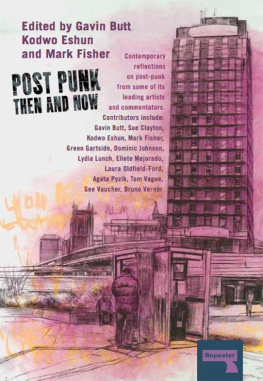

Post-Punk Then and Now

Post-Punk

Then and Now

Edited by Gavin Butt,

Kodwo Eshun

and Mark Fisher

Contents

Preface

Post-Punk Then and Now is based on a series of talks, lectures, and discussions organised by Gavin Butt, Kodwo Eshun, and Mark Fisher in the autumn of 2014. The series was part of the Public Programme of the Department of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London. The motivations for organising the series were anything but academic. For all three organisers, who were teenagers during the post-punk period, post-punk served as a heady initiation into culture. In its restlessness, its allusiveness, its overreaching, post-punk vigorously affirmed the possibility that culture could be at once popular, experimental and intellectually-driven. Post-punk happened at a particularly fraught historical juncture: it came at the end of a long wave of extraordinary invention in popular music culture, but it also coincided with the rise of what Stuart Hall called Thatcherism. The Post-Punk Then and Now series took place some 35 years after the election of Margaret Thatcher, when another Conservative Prime Minister was presiding over an austerity programme which seemed set to implement the final phase of neoliberalism. This therefore seemed a particularly opportune moment to gather together musicians, critics and artists some of whom directly participated in the original post-punk moment, some of whom came to it later for a sustained ten-week examination of post-punk and its legacy. In this volume, we have sought to preserve the energy and the spirit of the conversations which took place in that ten-week period. Perhaps more than most, this book is the product of collective work, and we would like to thank all the speakers for their hard work in assisting us to convert the series into a book.

1 Introduction

Gavin Butt, Kodwo Eshun, and Mark Fisher in Conversation (2|10|14)

Gavin Butt: Weve organised this programme of talks together because we share an interest in post-punk art and music, and the era that gave rise to them. Given that there is relatively little scholarship on the period, we thought it would be a good idea to put together a series of events at Goldsmiths involving in-conversations and talks by leading post-punk artists and musicians, alongside some new critical voices on the subject. One of the questions that cropped up as we began to think about doing this was: Why post-punk now? Why are the three of us interested in post-punk at this particular historical juncture? And why, given that so many of you have turned out today, is this relatively narrow period in cultural history of interest to you too? So we thought wed try and answer that question today, or at least begin to answer that question in a rudimentary way, by having a three-way conversation before opening up to hear your contributions and ideas.

I think I became conscious of the fact that post-punk was beginning to occupy my thoughts over the past few years as I began to reflect on the post-punk scene in the northern English city of Leeds, which is where I did my PhD at the university. There had been a very dynamic and interesting scene that preceded my time there, which I caught the tail-end of, and which was still in the air, if you like, in the late 80s when I was there. But, before that, I was also a fan and fellow traveller of many post-punk acts from differing city scenes across the UK and elsewhere. I guess, as I look back, I have begun to assess the formative impact of this time upon my political and aesthetic values, as well as upon my mature intellectual and cultural preoccupations. I discovered, quite by chance, that other professor friends of mine Jennifer Doyle, from the University of California Riverside, and the late Jos Muoz, former Professor in Performance Studies at NYU had also, quite independently, begun research on punk and post-punk at more or less the same time. Since we are or rather were all of the same age in our mid-40s, it perhaps wouldnt be unreasonable to answer the question Why post-punk now? by saying its a middle-aged thing, and that our interest in it is explained away as the expression of a generational nostalgia, of us enjoying the pleasure of returning to the primal scene of our youths. Im sure there is some mileage in this. But I know Mark, Kodwo, and I are not happy to let the explanation rest there in large part because understanding a return to post-punk as simply and only nostalgic obscures any possible exploration into its specific conditions of creation, and naturalises interest in it to normatively understood stages of an individual life-cycle.

Another way of looking at things would be to say that only now does post-punk seem, as a period, remote enough from our contemporary moment to allow us a good enough vantage point to turn towards it and begin to understand it historically. Given that the conditions of cultural possibility then seem so remote, so markedly different to those of our neoliberal present, perhaps it is only now we have travelled so far that we can more fully appreciate exactly how different everything was.

For those of you who dont know, the post-punk period is normally characterised as existing from the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, usually from 1978, which is the year that the Sex Pistols split up, to 1984 or 1985, which of course in this country saw the miners strike and their ultimate defeat, with miners trudging back to work, facing an uncertain future. This was a future which, in many ways, is now our present-day, neoliberal reality. Mark, in his book Ghosts of My Life, has much to say about the futures of post-punk, the futures that post-punk artists and musicians envisaged, and about what has befallen those imagined futures today. His book is a sustained exploration of what was once in post-punk a ready cultural capacity to orient oneself by radical visions of what might yet come.

Maybe Ill turn to Mark first, to ask for some observations from him. Is this something the imagining of an alternative future that you think has become more difficult in contemporary times? Can you say a little bit about what you value about looking back to then from the vantage point of now?

Mark Fisher: I think the first thing to say is that, in a certain way it is a bad sign that we are interested in post-punk in the way that we are. As we came in, we listened to a Fad Gadget track it didnt sound like something from 30 years ago. 30 years back from post-punk would take you to 1948, 1949, to something like Glenn Miller: who knew what the music of 1948 was, who was particularly interested in it in the late 70s? Certainly, anyone who did listen back to music of the late 40s then could not have experienced that music as sounding as if it belonged in any way to the contemporary moment of the 1970s. But I think, faced with many examples of post-punk, we are confronted with something that does feel uncannily contemporary.

GB: In what ways Mark?

MF: Well, it just doesnt sound outmoded. Ironically, much post-punk might have sounded more out-of-date in 1983 than it does now, because theres been a flattening of cultural time since then. Post-punk was an example of what Ive called popular modernism. The principle behind post-punk was the popular-modernist idea that you couldnt repeat things, you couldnt use forms that had become kitsch and yesterdays innovation was todays kitsch. So post-punk was driven by a principle of difference and self-cancellation; a constant orientation towards the new, and a hostility towards the outmoded, the already-existent, the familiar. Thats why Simon Reynolds called his book on post-punk

Next page