Faber Forty-Fives is a series of six short ebooks that between them tell the story of British pop music from the birth of psychedelia in the late sixties, through electric folk, glam, seventies rock and punk, to the eclecticism of post-punk in the late seventies and early eighties. Each book is drawn from a larger work on Fabers acclaimed music list.

PUBLIC IMAGE BELONGS TO ME: John Lydon and PiL

Public Image Ltd

Ever get the feeling youve been cheated?

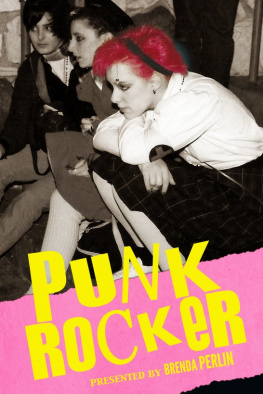

Johnny Rottens infamous parting shot to the audience at Winterland, San Francisco, on 14 January 1978, was not a question so much as a confession. Despite being the frontman of the most dangerous band in the world, Johnny was bored sick of The Sex Pistols music, tired of his own Rotten persona, disappointed with how punk as a whole had panned out. Winterland was the last date of the Pistols turbulent debut tour of America, and a few days later the band disintegrated in acrimonious confusion.

Rottens disillusionment had been brewing for months. The first public sign occurred during The Punk and His Music, a 16 July 1977 show on Londons Capital Radio, during which Rotten voiced his frustration with the predictability of most punk bands: You do feel cheated. There should be loads of different things. Spliced together from interview chat and records selected by Rotten, the show also revealed that the singer had far more diverse and sophisticated taste in music than his public image suggested. If you tuned in anticipating nothing but punk, you were immediately thrown for a loop by the first selection, Tim Buckleys Sweet Surrender a lush, sensual R&B song swathed with orchestral strings. Over the next ninety minutes Rotten further tweaked expectations, playing languid roots reggae, solo efforts by former Velvet Underground members Lou Reed, John Cale and Nico, a surprising amount of hippie-tinged music by Can, Captain Beefheart and Third Ear Band, and two tracks by his hero Peter Hammill, a full-blown progressive rocker.

Just about everything Lydon played on Capital gave the lie to Punk Myth #1: the early seventies as cultural wasteland. And, if this were not treasonous enough, he also broke with his Malcolm McLaren-scripted role as cultural terrorist by effectively outing himself as an aesthete. Along with his hipster music choices, the interview revealed a sensitive, thoughtful individual rather than the thug-monster of tabloid legend.

For Rotten, this image makeover was a matter of survival. A month before his radio appearance, the Pistols anti-Jubilee single God Save the Queen had defied airwave bans and record-store embargoes to become the best-selling single in the country. Demonized by the tabloids, Rotten was repeatedly attacked by enraged royalist thugs. Scared, scarred, in practical terms almost under house arrest, he decided to take control of his destiny. His anarchist/Antichrist persona originally Rottens own creation, but hyped by Pistols manager McLaren and distorted by a media eager to believe the worst had spiralled out of control. Agreeing to do the Capital Radio interview without consulting his management, Lydon embarked on the process of persona demolition that would soon result in Public Image (the song) and Public Image Ltd (the group).

During The Punk and His Music, Lydon sounded frail and vulnerable as he discussed the street attacks: Its very easy for a gang to pick on one person and smash his head in its a big laugh for them, and its very easy for them to say, What a wanker, look at him run away! I mean, whats he meant to do? Positioning himself as victim and revealing his feelings of humiliation, Rotten deliberately rehumanized himself.

This naturally incensed McLaren, who accused Rotten of dissipating the bands threat by revealing himself as a man of taste. McLaren saw the Pistols as anti-music, but here was the groups frontman waxing lyrical about his eclectic record collection and gushing, I just like all music I love my music, like a fucking hippie! From that point onwards, McLaren decided that Rotten was at heart a constructive sissy rather than a destructive lunatic, and he focused his energy on moulding the more suggestible Sid Vicious into the Pistols true star, a cartoon psychopath, wanton and self-destructive.

In the latter months of 1977, a chasm grew between Rotten and the other Sex Pistols that mirrored the polarization of punk as a whole into arty bohemians versus working-class street toughs. Rotten came from an impeccably deprived background, but his sensibility was much closer to that of the art-school contingent. He wasnt the unemployed guttersnipe mythologized by The Clash, but earned decent money alongside his construction-worker dad at a sewage plant, and worked at a playschool during the summer. And, although he often professed to hate art and despise intellectuals, he was well read (Oscar Wilde was a favourite) with fierce opinions (Joyce was not). Where Steve Jones and Paul Cook were early school-leavers, Rotten had even made a brief foray into further education, studying English literature and art at Kingsway College. Above all, Rotten was a music connoisseur. He couldnt play an instrument or write melodies, but he had a real sonic sensibility and a sense of possibilities much more expansive than those of his fellow-Pistols.

The reggae and art-rock that Rotten played on The Punk and His Music sketched out the emotional and sonic template for Public Image Ltd. When he talked about identifying with Dr Alimantados Born for a Purpose, a song about being persecuted as a Rasta, you got an advance glimpse of PiLs aura of paranoia and prophecy: Rotten as visionary outcast, an internal exile in Babylon UK. Musically, what he loved about Beefheart and the dub producers was their experimental playfulness: They just love sound; they like using any sound. Effectively, The Punk and His Music offered a listening list for a post-punk movement yet to be born; hints and clues for where next to take the music.

Punk seemed to be over almost before it had really begun. For many early participants, the death knell came on 28 October 1977 with the release of Never Mind the Bollocks. Had the revolution come to this, something as prosaic and conventional as an album? Bollocks was product, eminently consumable. Rottens lyrics and vocals were incendiary, but Steve Joness fat guitar sound and Chris Thomass superb production thickly layered, glossy, well organized added up to a disconcertingly orthodox hard rock that gave the lie to the groups reputation for chaos and ineptitude. Lydon later blamed McLaren for steering the rest of the band towards a regressive mod vibe, while admitting that his own ideas for how the record should have sounded would have rendered it unlistenable for most people because they wouldnt have had a point of reference.