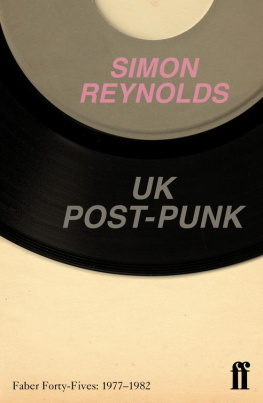

Grappling with a period as extended seven years, 19781984 and teeming with simultaneous activity as post-punk presented some problems in terms of organising the material. With so many things happening in parallel, straight chronology obviously wasnt an option. My solution was to break up the period into micro-narratives, most of them determined by geography: city-based scenes (New Yorks No Wave and mutant disco eras, for instance), regions (Ohios ClevelandAkron scene), or whole countries (Scotland). Other chapters are based on genre or sensibility: industrial, synthpop, New Pop, and so forth. Some are oriented around particular clusters of artists: the milieux of Rough Trade and 2-Tone, along with kindred-spirit groups not on either label. In other cases, two artists are paired because of direct links and/or an affinity: The Pop Group and The Slits shared common members and were on the same label at one point; Wire and Talking Heads had no such links but still seemed to belong together. Because each micro-narrative is followed from its earliest beginnings to its conclusion (or what felt like the best cut-off point), Rip It Up and Start Again proceeds in a sort of three steps forward, two steps back fashion. But, by and large, each new chapter starts a little bit further along the historical timeline than the previous one, and by the end of the book the events are taking place in 19834. For a sense of fully integrated chronological flow, consult the Timeline near the end of the book, and marvel at the sheer density of simultaneous post-punk action.

Punk bypassed me almost completely. Thirteen going on fourteen at the time, growing up in a Hertfordshire commuter town, I have only the faintest memories of 1977-and-all-that. I vaguely recall photo spreads of spiky-haired punks in a Sunday colour supplement, but thats it really. The Pistols swearing on television, God Save the Queen versus the Silver Jubilee, an entire culture convulsed and quaking I simply did notnotice. As for what I was into and up to instead well, its a bit of a haze. Was 1977 the year I wanted to be a cartoonist? Or, having moved on to science fiction, did I spend my time systematically working through the local librarys cache of Ballard, Pohl, Dick? All I know for sure is that pop music scarcely impinged on my consciousness.

My younger brother Tim got into punk first, a godawful racket coming through the bedroom wall. On one of the many occasions I went in there to complain, I must have lingered. The profanity hooked me first (I was fourteen, after all): Johnny Rottens Fuck this and fuck that/Fuck it all and fuck her fucking brat. More than the naughty words themselves, though, it was the vehemence and virulence of Rottens delivery those percussive fucks, the demon-glee of the rolled rs in brrrrrrrat. Theres been a thousand carefully reasoned theses validating the movements sociocultural import, but if anyones really honest, the sheer monstrous evil of punk was a huge part of its appeal. The sickness of Devo, for instance Id never heard anything so creepy and debased as their early Stiff single Jocko Homo b/w Mongoloid, brought round to our house by a far more advanced friend.

When I got into the Pistols and the rest, around the middle of 1978, Id no idea that this was all officially dead. The Pistols were long split; Rotten had already formed Public Image Ltd. Because Id been otherwise occupied and missed the entire birth, life and death of punk, I also cannily skipped the mourning after that sickening 78 crash experienced by almost everybody who was there and aware during the exhilarating 77 rush. My belated discovery of the movement coincided with when things began to pick up again, with what soon became known as post-punk the subject of this book. So I was listening to X-Ray Spexs Germ FreeAdolescents, but also the first PiL album, Talking Heads Fear of Music, and Cut by The Slits. It was all one bright, bursting surge of excitement.

Music historians celebrate being in the right place at the right time: those critical moments and locations when and where revolutions are spawned. Which is tough on the rest of us, stuck in suburbia or the provinces. This book is for and about the people who were not there at the right time and place (in punks case, London and New York circa 1976), but who nevertheless refused to believe it was all over and done with before theyd had a chance to join in.

Young people have a biological right to be excited about the times in which theyre living. If you are very lucky, that hormonal urgency is matched by the insurgency of the era your innate adolescent need for amazement and belief coincides with a period of objective abundance. The prime years of post-punk the half-decade from 1978 to 1982 were like that: a fortune. Ive come pretty close since, but Ive never been quite as exhilarated as I was back then. Certainly, Ive never been so utterly focused on the present.

As I recall it now, I never bought any old records. Why would you? There were so many new records that you had to have that there was simply no earthly reason to investigate the past. I had cassettes of the best of The Beatles and the Stones taped off friends, a copy of The Doors anthology Weird Scenes Inside the Goldmine, but that was it. Partly this was because the reissue culture that inundates us today didnt exist then; record companies even deleted albums. As a result, huge swaths of the recent past were virtually inaccessible. But mainly it was because there was no time to look back wistfully to something through which youd never lived. There was too much happening right now.

I didnt think of it in this way at the time, but, in retrospect, as a distinct pop cultural epoch, 197882 rivals those fabled years between 1963 and 1967 commonly known as the sixties. The post-punk era certainly rivals the sixties in terms of the sheer amount of great music created, the spirit of adventure and idealism that infused it, and the way that the music seemed inextricably connected to the political and social turbulence of the times. There was a similar mood-blend of anticipation and anxiety, a mania for all things new and futuristic coupled with fear of what the future had in store.

Not that Im especially patriotic or anything, but its also striking how both the sixties and post-punk were periods during which Britannia ruled the pop waves. Which is why this book focuses on the UK, plus those American cities where punk happened in any major way: the twin bohemian capitals of New York and San Francisco; Ohios post-industrial dreadzones Cleveland and Akron; college towns like Boston, Massachusetts, and Athens, Georgia. (For reasons of sanity and space, I have regretfully decided not to grapple with European post-punk or Australias fascinating but deep underground scene, except for certain key groups such as DAF, Einstrzende Neubauten and The Birthday Party, all of whom significantly impacted on Anglo-American rock culture.) In America, punk and post-punk were much less mainstream than in the UK, where you could hear The Fall and Joy Division on national radio, and where groups as extreme as PiL had Top 20 hits which, via Top of the Pops, were beamed into ten million households.

I have subjective and objective reasons for writing this book. Foremost among the latter is that post-punk is a period thats been severely neglected by historians. There are scores of books on punk rock and the events of 19767, but virtually nothing on what happened next. Conventional histories of punk generally end with its death in 1978, when the Sex Pistols auto-destructed. In the more extreme or sloppy accounts TV histories of rock are particularly culpable it is implied that nothing of real consequence happened between