The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Christopher Chisholm Parfit

CONTENTS

Part I:

Part II:

Part III:

Part One

CONTACT

CHAPTER ONE

April 2004

It was a clean but restless day, with hard light on the water and an edge in the north wind, the kind of day in which the sky doesnt tell you much except not to settle in.

It was the off-season in the islands along the border between the United States and Canada on the west coast of North America, in one of the few places where the border doesnt go in a straight line. The marina at the Rosario Resort and Spa on Orcas Island, about a hundred air miles north of Seattle, was mostly quiet, except for a few uneasy sailboats with masts and lines clattering like empty flagpoles.

The boat ride from the customs dock had taken about half an hour in lumpy water with a cold wind. All we had was an open twenty-foot boat with an outboard motor and a leaky canvas top, and there had been forty-five minutes of splash and spray even before we got to the customs dock, crossing from our island home in Canada. So Suzanne and I tied up with relief and walked up the dock toward the hotel and into the life of a whale.

We were joining a group of people whose interest or profession was the management of marine mammals. They gathered in a big conference room on rows of good padded chairs, not the folding metal kind. The long table at the front had two tablecloths and a short skirt on top of a long one that reached the ground so you couldnt see people in the panel of speakers wiggle their feet when they were exasperated at what their neighbors were saying. It was quiet, except for what you were supposed to hear.

I sat in one of the front rows. Suzanne was somewhere farther back. We sat with our small video cameras on tripods next to us. We were writing an article for Smithsonian magazine, not making a movie, but we used cameras for backup for our imperfect notes and because our editors wanted evidence, and cameras are good at evidence.

The room was full of the things that humans do: voices murmuring, chairs moving, clothes rustling, people crossing their legs and leaning forward, leaning back. We were so many and so close that we shared the air as intimately as our voices. We became a massed breathing thing packed into a room, like a school of herring leaning into the tide.

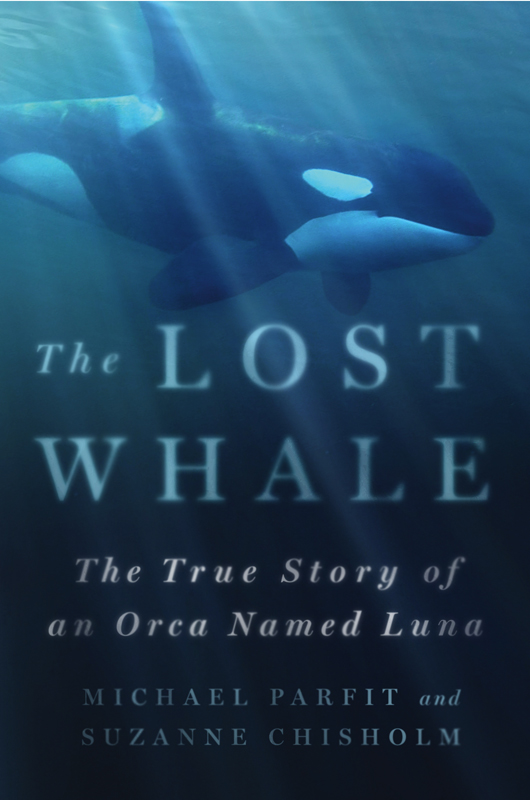

And the voices all turned one way, too. All spoke of one living being who was not there, as if all of us were whispering together about a movie star who should have treatment, or a candidate who needed advice, or a romantic thief who should be caught, or a soul to be saved with our wisdom. The missing subject of all this talk was a killer whale, an orcaa very young one.

Suzanne and I had seen photos in newspapers of a small orcas head poking up beside a dock, with kids leaning over the side to touch his nose, or of him raising his head to look into boats full of delighted people. These shots illustrated bits of text about how the young orca, whom people called Luna, had become separated from his pod and turned up all alone in a distant fjord, where he had started to befriend humans. The most recent stories reported that the Canadian government was planning to solve this problem by catching the little whale and moving him.

There was a shot from one newspaper in which Luna was practically touching noses with a black dog on a boat. There were photos of hands reaching out, and the whale lifting himself partly out of the water to touch them. There were photos of people rubbing the whales tongue. The images had been printed all over the world. We had those pictures clipped and in our files, but we didnt need to bring them with us, because everyone else here had the same shots, stuffed in their briefcases or seared into their minds.

* * *

A man named Marc Pakenham sat at the table and spoke. He had a large and flexible face sculptured with broad strokes. His expression seemed to be burdened by a thoughtful melancholy.

This whales character has been maligned a little bit over the last few years, he said.

Not knowing the story, we didnt know what he was talking about. But everybody else seemed to understand.

In my experience, he went on, and that of the other people who have worked with himand I know Kari and Erin and a few other people have had occasions where weve been closer to Luna than we wanted to beI dont think anyone can fail to be moved by the fact that this is a good whale.

If wed been doing an interview with Marc, we could have asked him why, exactly, he felt the need to defend the moral character of this whale. Who was attacking it? But we said nothing. Marc continued his defense.

If there is such a thing as a bad whale, he said, this is not a bad whale.

Next to Marc at the long table sat Kari Koski, one of the women he had been talking about, who had spent a few weeks working with Marcs organization in Lunas neighborhood. She was almost the opposite of Marc. He seemed weighed down with some kind of wry sorrow, but she was not. She was radiant without seeming nave, like a person who knows the darkness but shines anyway because shining feels better. She spoke of Luna as if he were a child in her family, as if she could pour her love for him into the room, knowing she had enough to flood us all with it.

Weve got a little whale thats coming up to the boat or the dock, she said, and hes looking you in the eye, and hes squeaking at you, and its what everybody comes out on a whale-watching trip hoping and wishing to get, its a personal communication and interaction with a whale.

She glanced around the room with an affectionate, encompassing look.

And I think were up against a lot, she said, when were asking people to put their human emotions aside.

* * *

The meeting was full of detailed information that made only partial sense to us. The whale was a member of a group of whales called L Pod, part of a community of just over eighty, known as the Southern Residents, that spent about six months of the year in the waters near the southern end of Vancouver Island. The whales were officially endangered and were much beloved by the millions of people who lived near them.

The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) had announced that it was going to catch the little whale in the remote fjord where he had been for two and a half years and move him closer to the pod to which he belonged. There were several options, but the most probable involved catching him by subterfuge or force, putting him in a net pen, testing him for several days, bolting a satellite tagging device to his dorsal fin, lifting him into a truck, driving him about two hundred miles, and putting him back in the water near the Vancouver Island city of Victoria.

There was no disagreement in the room, but it was clear that there had been. Everyone went to great lengths to praise everyone else for at last working together to solve the problem. Everyone smiled at one another and shook hands. The smiles looked sincere.