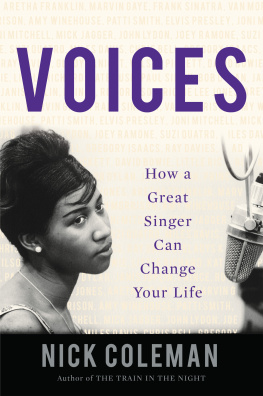

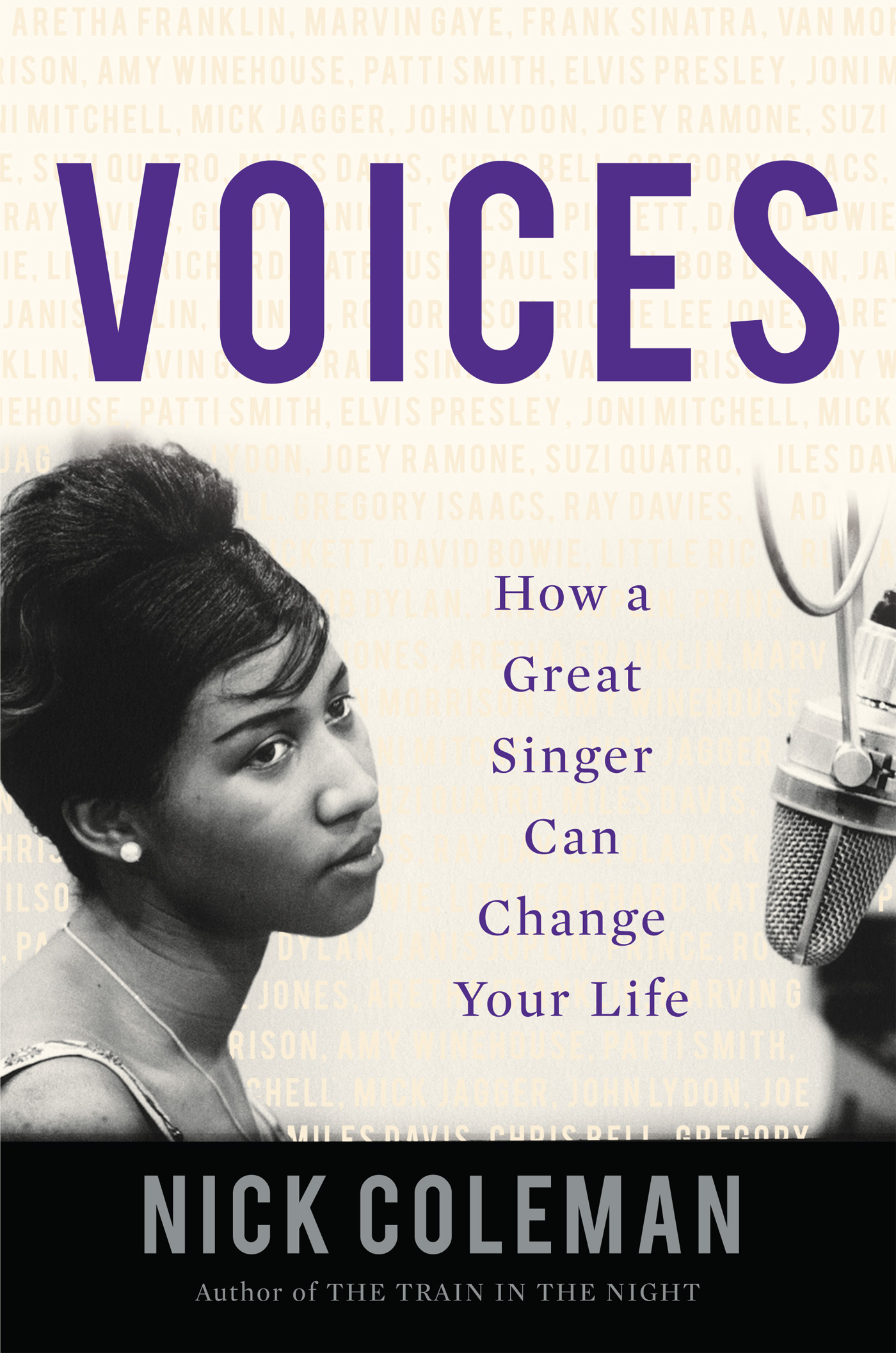

ALSO BY NICK COLEMAN

NONFICTION

The Train in the Night: A Story of Music and Loss

FICTION

Pillow Man

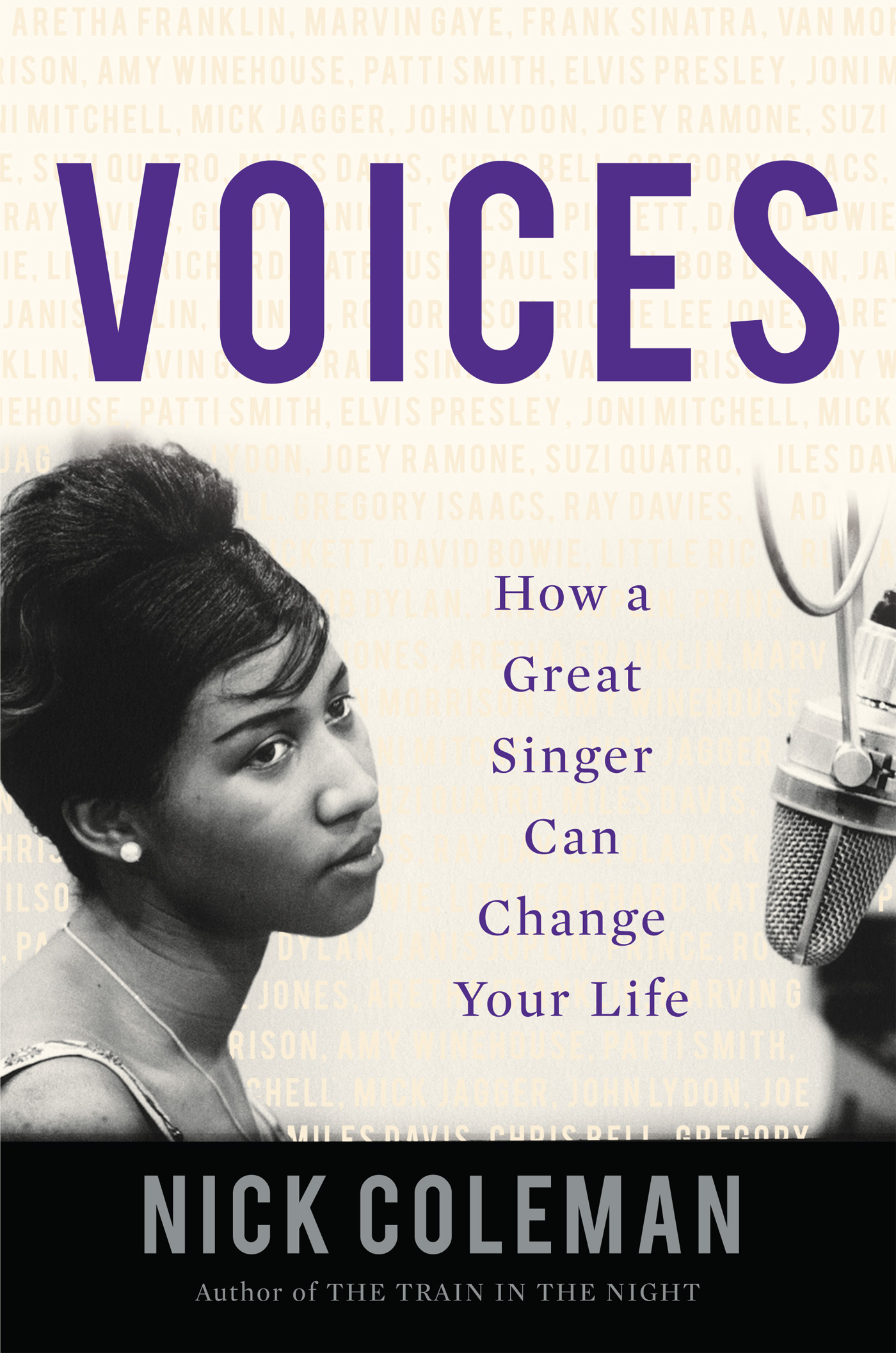

Voices

Copyright 2017 by Nicholas Coleman

First published in 2018 by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage. Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies.

First Counterpoint hardcover edition: 2018

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Coleman, Nick, 1960 author.

Title: Voices : how a great singer can change your life / Nick Coleman.

Description: First Counterpoint hardcover edition. | Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint Press, 2018. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018002256 | ISBN 9781640091153

Subjects: LCSH: Popular musicHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML3470 .C6236 2018 | DDC 782.42164/117dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018002256

Jacket design by Donna Cheng

Book design by Jordan Koluch

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR TOM AND BERRY

Whooooooooooooooooo!

LITTLE RICHARD, 1956

Love... is a losing game.

AMY WINEHOUSE, 2006

Contents

Preface

P atti Smith is crammed on to a balcony in a stately ballroom in Stockholm with a small orchestra.

Shes up there on behalf of Bob Dylan to accept his Nobel Prize for Literature, and she is going to sing his famous song A Hard Rains A-Gonna Fall to the accompaniment of small guitar, lap steel, and strings. She is dressed in a black tuxedo and planted like an Easter Island statue.

The audience is composed of the great and the good of Swedish culture and the Swedish royal family, who are all done up in formal fig, bibs and tuckers, gowns and jewelry, stoles and tiaras. And medals. They are arrayed formally, as for a state portrait. Smith has no medals though her white shirt beneath the oversized tuxedo is nicely ironed. Her steel-colored hair is long and heavy and parted severely in the middle. She is like Albrecht Drer, who did not do state portraiture. She is also faintly reminiscent of Buster Keaton.

The introduction is strummed artlessly on two chords. Smith sings. The sound she and the guitarist make is as severe as her hairstyle and so is the intent of the words she sings. Yet she is singing beautifully with total involvement, her rich, twangy contralto, with its flattened vowels and its inclination to yodel, driving hard and straight into the language, as if the song had been written this year, the year of all hateful years, 2016.

All is suspense.

But then, after a couple of minutes, Smith appears for a moment to be overwhelmed. She stops singing. She gulps. Im so sorry, she says, blanching. She tries to carry on... Unh... But it wont come. She apologizes again and looks up in appeal to the conductor standing above her left shoulder. Im sorry. Could we start that section ... ? I apologize. She looks out into the audience. They are frozen in their places. Im so nervous. She forces an agonized smile.

There is sustained, kindly applause from the audience. You can almost hear the jewelry rattling.

And soon enough she goes again with renewed resolve until, a minute or two later, she dries once more, and again looks up at the conductor with the mute appeal of a frightened child. The conductor, out of shot, presumably makes encouraging faces because Smith, suddenly somehow heartened, hooks quickly back into the song and then seems to grow, to expand in her place and to move her hands a little and then her shoulders and then to pace, striding on the spot, no longer an Easter Island statue but a living, breathing, marching embodiment of the hipster-symbolist song lyric she is singing, all about the doom of the world and the love that may save it. She reaches the end of the song in a sea of strings.

It is impossible to watch without tears.

It is also as great a passage of singing as you are ever likely to hear, if singing is to you not about the observance of musical correctitude and extravagant display and signaled passion and technical virtuosity, but about the inhabitation of the moment up to and including the moment when the moment bursts.

Introduction

Hearing Voices

T he human voice is the very first medium that we take for a message.

At the time, being babies, we do not understand that what we are hearing is a medium and are unable fully to interpret the message. But thats what happens. We hear a sound; we listen; we intuit that the sound means good; we learn quickly to draw comfort from it and to enjoy feelings of expectation and curiosity ... and then we learn to shape identity from it. Its possible of course that we do the identity thing firstour mothers voice, our fathers voice: the first intimations in life that rowdy, meaningless chaos does in fact submit to meaning, the message I love you boring like a drill through the big-bang debris of not knowing anything at all.

But the message is not encoded in words. There are no words yet. There is only sound, as there was only sound in the womb. It is the sound of the voice that makes the feeling happenthe tone and timbre of the voice, its comforting rhythm and, of course, its sheer familiarity in its association with touch, proximity, warmth, comfort. And our capacity for feeling these things develops as we develop, keeping an even pace, side by side, as if going somewhere. From the very start of our lives we know that voices carry information, yes. But much more than that, they also express emotionthey confer emotion. They stimulate it. We know, even without the involvement of clearly articulated and comprehended language, that voices are vessels brimming with stuff: that a voice can itself be a message. We learn that we dont actually need to hear the words of an altercation to know that anger is being expressed, even at low amplitude, even in a whisper. Equally, we can hear love through gibberish. A voice is a ship, and sometimes it is enough to know that it is a ship and that it is coming, whether or not we can picture in our minds precisely what it carries in darkness below the waterline.

Its fair to say, then, that before words are distinguishable, voices make some sort of case for our close attention. We learn from the start to read voices and to engage with them, as if the voice itself and not the language is the primary agent of meaning. Voices invite inference. They switch us on. Even before we have words with which to encode and decode meaning, voices are an event.

And then we learn that voices have other modes. They can sing, too.

* * *

I have no idea when singing first became noticeable to me. In our house, when I was growing up, singing was just what happened. It was part of the everyday fabric of life, not in any particularly attractive or impressive way but in a comfortable, pleasing, homely way; because it was quite a nice thing to do and because singing constituted a significant feature of the familys social breathing. There was nothing fancy going on herethere was no agenda. Im afraid we just sang. We sang neither cutely nor Von-Trappishly, and certainly not with any zealin fact we sang in rather a methodical way, without any great consideration of how we might sound to others or even what the point of singing was. We sang in church as we sang in school assembly, because it was required. We sang at home because it appeared to give my parents pleasure and because it was normal. None of us sang particularly well. We sang either solo or in harmony, sometimes contrapuntally, never in unison (whats the point of that?), sometimes accompanied, sometimes not. Victorian parlor songs, church music, carols, arias, lieder, A. A. Milnethe middle-to-highbrow middle-class repertoire of the mid-twentieth century ...

Next page