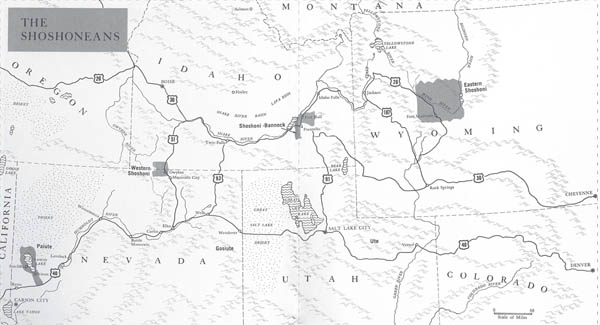

THE SHOSHONEANS

RECENCIES Research and Recovery in Twentieth-Century American Poetics

MATTHEW HOFER, Series Editor

This series stands at the intersection of critical investigation, historical documentation, and the preservation of cultural heritage. It exists to illuminate the innovative poetics achievements of the recent past.

Other titles in the Recencies series available from the University of New Mexico Press:

Amiri Baraka and Edward Dorn: The Collected Letters edited by Claudia Moreno Pisano

THE SHOSHONEANS

The People of the Basin-Plateau

EXPANDED EDITION

Text by Edward Dorn

Photographs by Leroy Lucas

Foreword by Simon J. Ortiz

Edited by Matthew Hofer

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Dr. Sven Liljeblad, the linguist, who pointed out a great deal of monographic material I might otherwise never have come across. He is in no sense, of course, to be held responsible for my interpretations.

To Miss Alice McClain, of the Idaho State University Library, I want to express my thanks for her aid with library materials.

I want to thank my wife for her very patient help with the manuscript.

In various tangible and intangible ways the following people were helpful to both the photographer and writer: Mr. Max Pavesic, Mr. Raymond Obermayr, Professor E. W. Dawson, Mr. Jack Fitzwater, Mr. Jeff Phippeny.

Original text and photographs 1966 by Edward Dorn and Leroy Lucas

Expanded edition 2013 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved.

Published 2013 by arrangement with the authors.

Printed in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 6

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed editon as follows:

Dorn, Edward.

The Shoshoneans : the people of the Basin-Plateau / Edward Dorn, Leroy Lucas, Matthew Hofer ; [foreword by] Simon J. Ortiz. Expanded edition.

pages cm

Originally published: New York ; William Morrow & Company, 1966.

ISBN 978-0-8263-5381-8 (pbk.) ISBN 978-0-8263-5382-5 (electronic)

1. Shoshonean IndiansPictorial works. I. Title.

E99.S39D67 2013

978.004974574dc23

2013026919

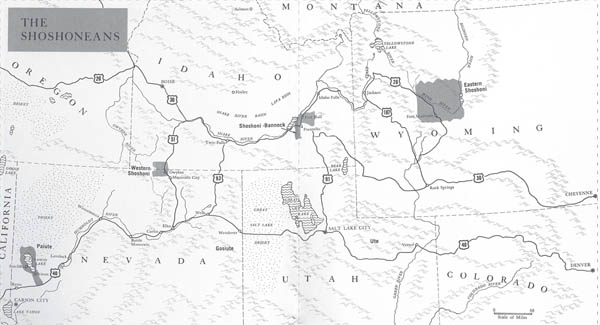

SHOSHONEAN FAMILY. The extent of country occupied renders this one of the most important of the linguistic families of the North American Indians. The area held by Shoshonean tribes, exceeded by the territory of only two familiesthe Algonquian and the Athapascan,may thus be described: On the N. the S.W. part of Montana, the whole of Idaho S. of about lat. 45 30', with S.E. Oregon, S. of the Blue mts., W. and central Wyoming, W. and central Colorado, with a strip of N. New Mexico; E. New Mexico and the whole of N.W. Texas were Shoshonean. According to Grinnell, Blackfoot (Siksika) tradition declares that when the Blackfeet entered the plains S. of Belly r. they found that country occupied by the Snakes and the Crows. If this be true, S.W. Alberta and N.W. Montana were also Shoshonean territory. All of Utah, a section of N. Arizona, and the whole of Nevada (except a small area occupied by the Washo) were held by Shoshonean tribes. Of California a small strip in the N.E. part E. of the Sierras, and a wide section along the E. border S. of about lat. 38, were also Shoshonean. Shoshonean bands also lived along the upper courses of some of the flanks of the Sierras, Shoshonean territory extended across the state in a wide band, reaching N. to Tejon cr., while along the Pacific the Shoshoni occupied the coast between lat. 33 and 34.

On linguistic grounds, as determined by Kroeber, it is found convenient to classify the Shoshonean family as follows:

I. Hopi.

II. Plateau Shoshoneans: (a) Ute-Chemehuevi: Chemehuevi, Kawaiisu, Paiute, Panamint, Ute, and some of the Bannock; (b) Shoshoni-Comanche: Comanche, Gosiute, Shoshoni; (c) Mono-Paviotso: Mono, Paviotso, part of the Bannock, and the Shoshoneans of E. Oregon.

III. Kern River Shoshoneans.

IV. Southern California Shoshoneans: (a) Serrano, (b) Gabrieleo, (c) Luiseo-Kawia: Agua Caliente, Juaneo, Kawia, Luiseo.

Frederick Webb Hodge, 1912

In 1835, the padres of Mission Santa Barbara transferred the San Nicolas Indians to the mainland. A few minutes after the boat, which was carrying the Indians, had put off from the island, it was found that one baby had been left behind. It is not easy to land a boat on San Nicolas; the captain decided against returning for the baby; the babys mother jumped overboard, and was last seen swimming toward the island. Half-hearted attempts to find her in subsequent weeks were unsuccessful: it was believed that she had drowned in the rough surf. In 1853, eighteen years later, seal hunters in the Channel waters reported seeing a woman on San Nicolas, and a boatload of men from Santa Barbara went in search of her. They found her, a last survivor of her tribe. Her baby, as well as all her people who had been removed to the Mission, had died. She lived only a few months after her rescue and died without anyone having been able to communicate with her, leaving to posterity the skeletal outline of her grim story, and four words which someone remembered from her lost language and recorded as she said them. It so happens that these four words identify her language as having been Shoshonean...

Theodora Kroeber

Contents

by Simon J. Ortiz

Photographs follow

Foreword

Simon J. Ortiz

I hadnt read The Shoshoneans for many years, and I was totally overjoyed when I found myself being asked to write a commentary that would be an introduction to a new publication of The Shoshoneans, a powerful and beautifully expressive book by the late Edward Dorn with photographs by Leroy Lucas, originally published in 1966. Vividly remembering the book, I said, At long last! since I was excited about the prospect of writing about a book I loved. Of course, obviously and immediately, I agreed to write such a commentary.

I began to reread Dorns wordsI call him Ed, by the waythat I remember first reading in 1968 or 1969. So much was happening during that period of time, including the publication of The Shoshoneans. I was a busy summer teaching intern at Rough Rock Demonstration School (RRDS) in Arizona on the Navajo Nation (reservation was the operative word back then, not Nation as it is now) and was a student during the regular year at the University of New Mexico College of Education. Soon I would begin full-time work as the public relations director at RRDS since the school was asserting and demonstrating local control in Indigenous (the usual operative word in common use then was Indian) education.

The time period also included those incipient years when anti-war protests against U.S. invasion and occupation of Vietnam in Southeast Asia were beginning. Activism plans, peace projects, and other such actions were being tactically organized, and they would soon be in place in full popular force. Theres a big difference between then in the latter 1960s and now in 2013, isnt there? Basically, popular activism was a cultural, social, and political dynamic movement within the American community.

It was evident that there was an unabashed national political movement underway. Soon, it would be in the mode of open public resistance against the Vietnam War, and these acts of resistance were, in effect, active protests of U.S. international policy. Much of it was within the thematic rubric of bringing the war home, and a good deal of it was led by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Weather Underground, an offshoot of SDS. It was also directed by voices from within the American community. I remember one of the RRDS summer interns in particular; he was an energetic, talkative guy named Blackburn, and he was an SDSer from Denver whose rhetoric was fiery and upfront!

Next page